Ancient Variants, New Insights: The Western Text of Acts Explained

The Western Text of Acts, preserved primarily in the fifth-century Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis, presents one of textual criticism's most fascinating puzzles: while standard manuscripts offer a streamlined apostolic narrative, this distinctive tradition expands the text by 8% to 10% with vivid details, theological clarifications, and pastoral adaptations that transform familiar stories into cinematic experiences. Recent scholarship, particularly Jenny Read-Heimerdinger's discourse analysis challenges traditional assumptions about textual priority by revealing sophisticated narrative patterns that may reflect early Jewish-Christian perspectives rather than later scribal embellishment. Instead of viewing these variants as corruptions to eliminate, this textual tradition invites us to see Acts as a living document--dynamically shaped by faithful communities who transformed Scripture from static text into evolving witness.

Greg Camp and Patrick Spencer

4/20/202523 min read

NOTE: This article was researched and written with the assistance of AI.

Key Takeaways on the Western Text of Acts

Substantial textual expansion: The Western Text, preserved primarily in fifth-century Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis, extends Acts by 8-10% with 3,642 additional words across 494 passages, transforming familiar apostolic stories into vivid, cinematic narratives with architectural details like "seven steps" during Peter's prison escape and strategic teaching schedules

Theological reshaping patterns: Three consistent editorial tendencies emerge—anti-Judaic bias that intensifies Jewish opposition (adding "blaspheming" to descriptions), diminished women's roles (changing "leading women" to "wives of prominent men"), and enhanced apostolic authority through expanded proclamation scenes that emphasize boldness and divine mandate

Contemporary scholarly revolution: Jenny Read-Heimerdinger's discourse analysis challenges traditional assumptions by arguing the Western Text may preserve Luke's original Jewish-Christian perspective, while critics like Zachary Dawson contend these variants reflect second-century theological priorities rather than authorial intent, creating vibrant ongoing debate about textual priority

Living Scripture paradigm: Rather than viewing variants as corruptions, the Western Text reveals how early Christian communities dynamically adapted Scripture for pastoral needs—from liturgical baptismal confessions (Ethiopian eunuch's declaration) to ethical reframing of the Apostolic Decree—demonstrating Scripture as community-shaped witness rather than static text

Introduction: The Text of Acts You Haven't Read

The Western Text of Acts, a distinctive version of the New Testament book, opens a remarkable window into the world of early Christianity, revealing how the apostolic story was shaped by vibrant faith communities. Preserved primarily in the fifth-century Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis, this textual tradition extends the narrative of Acts by approximately 8% to 10%, weaving in expansions, clarifications, and theological nuances that set it apart from the standard Alexandrian manuscripts found in most modern Bibles. Once dismissed as mere scribal errors, its variants are now at the heart of a lively debate--is this text an early draft of Acts, closer to the apostolic era, or a later adaptation shaped by second-century concerns?

By exploring the Western Text's unique features, its vivid examples, scholarly debates, and practical implications for ministry, we uncover a richer understanding of the early church and its enduring relevance for biblical study today. This article traces the Western Text's significance, its differences from other traditions, and how it invites us to engage with Scripture as a dynamic, community-shaped witness to the apostolic message

Podcast Episode: Re-reading Luke-Acts' Characterization in Codex Bezae (Part 1) | Interview with Jenny Read-Heimerdinger

What Is the Western Text of Acts?

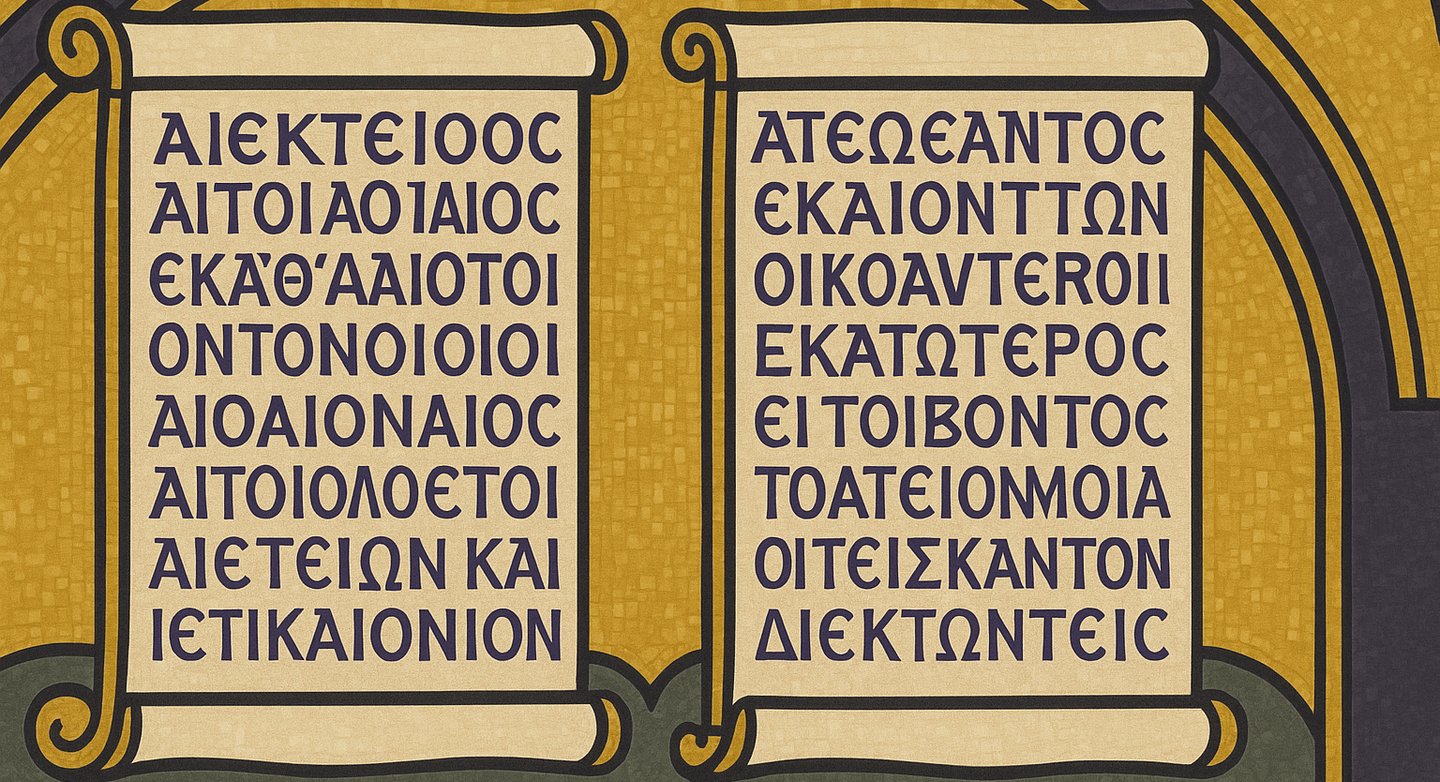

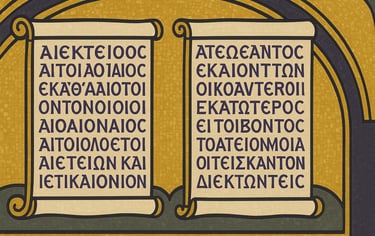

Imagine holding a manuscript that tells the story of the early church with details and flourishes absent from your Bible. This is the Western Text of Acts, primarily preserved in Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis, a fifth-century bilingual manuscript featuring Greek and Latin texts on facing pages. Known as ‘D’ in scholarly circles, this remarkable document is nearly complete in its preservation of Acts and extends the narrative by 8% to 10%, adding approximately 3,642 words of variation across 494 distinct passages, as documented by the Editio Critica Maior. Unlike the more concise Alexandrian manuscripts, such as Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus, the Western Text adopts a “free” approach to transmission, incorporating narrative expansions, theological clarifications, and vivid details that reflect the pastoral and liturgical concerns of early Christian communities.[1]

The Western Text’s influence extends beyond Codex Bezae. Early papyri like P29, P38, and P48, as well as Old Latin translations such as Codex Laudianus, preserve readings aligned with its characteristics. Citations from church fathers like Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Cyprian further attest to its circulation in the second and third centuries, challenging the outdated notion that the Western Text was confined to the western Mediterranean. Its geographical diversity suggests it was a widely embraced tradition, valued for its ability to make the apostolic narrative resonate with diverse audiences. For instance, where the standard text might leave a character’s motivation ambiguous, the Western Text often provides explanatory material, as if scribes sought to bridge gaps in the story for their communities.[2]

To contextualize the Western Text, it’s helpful to compare it with the Byzantine Text, which underlies traditional translations like the King James Version. The Byzantine tradition, emerging later in the ninth century, prioritizes harmonized grammar and theological polish, creating a smoother but less dynamic narrative. In contrast, the Western Text’s paraphrastic style feels raw and immediate, emphasizing substance over exact wording. Modern scholarship, using tools like the Coherence-Based Genealogical Method (CBGM), evaluates variants individually rather than by rigid text-type labels, recognizing that some Western readings may preserve early traditions. This shift has transformed how we view the Western Text, moving from dismissal as a corruption to appreciation as a vital witness to early Christian interpretation.[3]

Key Variants: Bringing the Early Church to Life

The Western Text of Acts doesn’t merely add words—it transforms familiar stories with details that illuminate the early church’s theology, practices, and daily life. One of the most striking examples is the Apostolic Decree in Acts 15:20, 29, where the Jerusalem Council outlines requirements for Gentile believers. The standard Alexandrian text lists four prohibitions: avoiding food polluted by idols, sexual immorality, strangled animals, and blood. The Western Text, however, omits “things strangled” and adds the negative Golden Rule: “do not do to others what you would not have done to you.” This shift reframes the decree from Jewish ritual laws to universal ethical principles, a reading cited by early fathers like Irenaeus and Tertullian. This variant suggests that second-century Christians were navigating tensions between Jewish roots and Gentile inclusion, offering a window into their theological priorities.[4]

Another vivid detail appears in Acts 12:10, during Peter’s dramatic escape from prison. The standard text states that Peter and the angel “went along one street” before parting. The Western Text specifies that they “went down the seven steps” first, a concrete architectural detail that evokes the layout of a Jerusalem prison. This addition, absent in other manuscripts, has the ring of eyewitness testimony, making it difficult to dismiss as a scribal invention. It invites readers to visualize Peter’s escape with cinematic clarity, grounding the miraculous in a tangible setting.[5] Similarly, in Acts 19:9, the Western Text notes that Paul taught in the hall of Tyrannus in Ephesus “from the fifth hour to the tenth” (11:00 AM to 4:00 PM). This practical detail suggests Paul strategically used the midday siesta hours, when workplaces closed, to maximize his audience, revealing his missionary ingenuity and work ethic.[6]

One of the best-known Western variants is the Ethiopian eunuch’s confession in Acts 8:37. In the standard text, after the eunuch asks, “What prevents me from being baptized?” the narrative moves directly to his baptism. The Western Text, preserved in the King James Version, inserts Philip’s condition: “If you believe with all your heart, you may,” followed by the eunuch’s declaration, “I believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God.” This addition mirrors early baptismal practices, reflecting how communities formalized conversions with explicit confessions of faith. Though absent in major Alexandrian manuscripts, its presence in early citations suggests it preserves an authentic tradition.[7]

A lesser-known but equally compelling variant occurs in Acts 18:9-10, where the Western Text expands Paul’s vision in Corinth. The standard text records the Lord encouraging Paul: “Do not be afraid, but speak and do not be silent, for I am with you.” The Western Text connects this to 1 Thessalonians 2:17-18, adding that Paul was hindered by Satan but reassured by God’s promise of “many people in this city.” This expansion creates a narrative bridge between Paul’s struggles and divine encouragement, weaving a cohesive arc across biblical books.[8] These variants, far from random, reveal a deliberate effort to clarify motivations, enhance theological connections, and make the apostolic story vivid and relatable.

Scholarly Debates: Unraveling the Western Text’s Origins

The origins of the Western Text have fueled scholarly debate for centuries, with each theory offering a unique perspective on its place in the transmission of Acts. In the late 19th century, Friedrich Blass proposed a bold hypothesis: Luke, the author of Acts, created two versions of his work. The Western Text, he argued, was a rough initial draft intended for Theophilus, rich with vivid details and local color, while the Alexandrian text was a polished revision for broader circulation. Blass pointed to expansions like the “seven steps” in Acts 12:10, which reflect intimate knowledge of Palestinian geography, suggesting an authorial hand rather than later scribal additions. Yet, the lack of similar dual editions for Luke’s Gospel and inconsistencies among Western manuscripts—such as variations in Old Latin translations—undermine this theory, leaving it as an intriguing but unproven idea.[9]

Albert C. Clark offered a different view, contending that the Western Text was the original, with the Alexandrian text resulting from scribal abbreviations. His philological analysis highlighted potential errors like haplography, where scribes might have skipped words, shortening the text. Clark’s theory gained attention for its focus on mechanical copying errors, but it faltered against the early attestation of Alexandrian manuscripts, such as Codex Sinaiticus, which date to the fourth century and predate many Western witnesses. The coherence of Alexandrian readings further weakened Clark’s argument, as they lack the erratic expansions characteristic of the Western Text.[10]

By the 20th century, James Hardy Ropes and Bruce Metzger represented the prevailing view that the Western Text is a secondary expansion. They argued that its additions—such as explanatory phrases and harmonizations with other biblical texts—reflect scribal embellishments rather than Luke’s original composition. Metzger, in particular, noted that Western variants often resolve narrative ambiguities, a hallmark of scribal activity. For example, in Acts 16:35-39, the Western Text explains the magistrates’ release of Paul and Silas by adding that they “remembered the earthquake,” a clarification absent in the Alexandrian text. Ropes and Metzger saw these as creative but unauthorized additions, shaped by oral traditions and community needs, positioning the Alexandrian text as closer to Luke’s original.[11]

Recent scholarship has introduced fresh perspectives, notably from Jenny Read-Heimerdinger and Josep Rius-Camps, who challenge the dismissal of the Western Text. Their work, grounded in detailed linguistic analysis, suggests that Codex Bezae may preserve Luke’s original composition, with the Alexandrian text as a later revision. This argument, explored further through discourse analysis, marks a significant shift in the debate, inviting a closer look at the Western Text’s narrative and theological coherence.[12]

Modern textual criticism, guided by the Coherence-Based Genealogical Method (CBGM), has moved beyond rigid categories like “Western” or “Alexandrian.” Scholars now evaluate each variant based on its coherence and early attestation, recognizing that some Western readings may preserve authentic traditions. The Editio Critica Maior, analyzing 7,600 variation units in Acts, reveals patterns of editorial shaping in the Western Text, suggesting a complex interplay of textual traditions. Projects like Text und Textwert further highlight this dynamic relationship, challenging earlier views that dismissed the Western Text as unreliable and affirming its value as a witness to early Christian interpretation.[13]

Discourse Analysis: A New Lens on the Western Text

Recently, Read-Heimerdinger and Rius-Camps revitalized the study of the Western Text through discourse analysis, a linguistic method that examines how verb tenses, conjunctions, word order, and participant references create cohesive narratives. Their multi-volume commentary on Acts argues that Codex Bezae’s text exhibits a remarkable internal unity, with consistent character development and theological themes that suggest it may reflect Luke’s original composition. Unlike traditional textual criticism, which focuses on isolated variants, discourse analysis explores the Western Text’s narrative flow, revealing patterns that point to deliberate authorial design rather than scribal patchwork.[14]

Read-Heimerdinger emphasizes the Western Text’s portrayal of the apostles as Jewish disciples navigating Jesus’ Messiahship within their cultural framework. For example, in Acts 1:6, the apostles ask Jesus, “Lord, are you at this time going to restore the kingdom to Israel?” The Western Text’s expansions throughout Acts highlight their gradual understanding of Jesus’ mission, reflecting a Jewish insider’s perspective. Linguistic features, such as the consistent use of the Greek article and connectives like “and” or “but,” create a tightly woven narrative that links episodes and characters in ways the Alexandrian text often simplifies. She argues that the Alexandrian text emerged as a later revision, streamlining the Western Text’s Jewish orientation to suit broader ecclesiastical needs in a Gentile-dominated church.[15]

This approach has sparked significant debate, with scholars like Zachary Dawson offering a critical perspective. He questions the reliability of Read-Heimerdinger’s conclusions, arguing that her focus on micro-level linguistic details—such as conjunctions or word order—leads to overly broad claims about authorship. He contends that larger syntactic structures, which discourse analysis often overlooks, are crucial for assessing textual originality. For instance, in the Apostolic Decree (Acts 15:20, 29), the Western Text omits “things strangled” and adds the negative Golden Rule, shifting the focus from Jewish ritual laws to universal ethics. Dawson sees this as evidence of second-century redaction, aligning with Gentile Christian priorities rather than a Jewish perspective, thus challenging Read-Heimerdinger’s claim of the Western Text’s priority.[16]

Dawson further critiques the over-reliance on discourse analysis as a substitute for traditional textual criticism. While acknowledging its value in highlighting narrative coherence, he argues that stylistic features, like the use of connectives, may reflect later editorial shaping rather than Luke’s original intent. Scholars such as Eldon Epp, David Parker, and Bruce Metzger echo this caution, suggesting that the Western Text’s apparent unity could result from a skilled redactor addressing second-century theological concerns. For example, the Western Text’s expansions often clarify ambiguities, such as adding explanatory phrases, a practice common in later manuscript traditions. This debate underscores the need for a balanced approach, integrating discourse analysis with other critical methods to fully understand the Western Text’s origins.[17]

Strengths of Discourse Analysis

Read-Heimerdinger’s method offers a fresh perspective by shifting attention from isolated variants to the Western Text’s narrative architecture. Her analysis uncovers subtle linguistic patterns that suggest authorial control, challenging the assumption that longer texts are inherently secondary. The Jewish perspective she identifies aligns with details like the “seven steps” in Acts 12:10, which reflect Palestinian geography unlikely to be invented by a Gentile scribe. By bridging textual criticism with literary analysis, discourse analysis makes the Western Text accessible to non-specialists, showing how its variants enhance storytelling and theological depth. This approach invites readers to see Acts as a dynamic narrative shaped by early Christian communities.

Limitations of Discourse Analysis

Critics like Dawson highlight the method’s limitations, particularly its focus on small linguistic details at the expense of broader syntactic analysis. The Western Text’s shift toward universal ethics in passages like the Apostolic Decree suggests a later editorial hand, undermining claims of a Jewish orientation. Overinterpreting stylistic features as evidence of originality risks speculative conclusions, especially when traditional textual criticism points to secondary redaction. Scholars argue that the Western Text’s coherence may reflect second-century priorities, such as clarifying narratives for Gentile audiences, rather than Luke’s initial composition. This tension invites further exploration of how linguistic tools can complement, rather than replace, established critical methods.

The discourse analysis debate enriches our understanding of the Western Text, highlighting its complexity and encouraging a nuanced approach to its study. While Read-Heimerdinger’s work opens new avenues, Dawson’s critique invites further scrutiny of textual priority claims, helping to sustain an ongoing, dynamic scholarly conversation.

Theological Tendencies: Shaping the Apostolic Narrative

The Western Text of Acts is not merely a collection of variant readings—it actively reshapes the apostolic narrative to reflect the theological and cultural priorities of early Christian communities. Its consistent patterns reveal how second-century believers interpreted and adapted the story of the early church, addressing pressing issues of identity, authority, and social dynamics. Three distinct theological tendencies stand out: an anti-Judaic bias that heightens tensions with Jewish communities, a reshaping of women’s roles to align with Greco-Roman norms, and an enhancement of apostolic authority to underscore the boldness and divine mandate of early Christian leaders. Each tendency offers a glimpse into the concerns of the communities that preserved and transmitted this text, illuminating the dynamic interplay between Scripture and its interpreters.

1. Anti-Judaic Bias

One of the most striking features of the Western Text is its tendency to amplify Jewish opposition to the early Christian movement, a pattern first systematically documented by Eldon Epp in his 1966 study. This anti-Judaic bias reflects the growing separation between Jewish and Christian communities in the second century, as Christians increasingly defined their identity apart from Judaism. In Acts 13:45, for example, the standard Alexandrian text describes Jews in Antioch as “filled with jealousy” when they saw the crowds drawn to Paul’s preaching. The Western Text intensifies this portrayal, stating that they “spoke against those things spoken by Paul, contradicting and blaspheming.” The addition of “blaspheming” casts Jewish opposition in a more hostile light, suggesting not just disagreement but active rejection of divine truth.[18].

Similarly, in Acts 24:9, where the standard text notes that Jews “joined in the attack” against Paul during his trial, the Western Text adds that they did so “with shouting,” evoking a chaotic and aggressive scene. This heightened rhetoric aligns with other passages, such as Acts 18:6, where the Western Text emphasizes Jewish resistance to Paul’s message, framing it as a deliberate rejection of the gospel. These changes are not random but reflect a theological agenda, likely shaped by second-century communities navigating tensions with Jewish neighbors. As Christianity spread in the Gentile world, such variants may have served to justify the church’s distinct identity, portraying Jewish opposition as a foil to Christian faithfulness.[19].

This anti-Judaic tendency has profound implications for understanding early Christian-Jewish relations. The Western Text’s editors seem to have adapted the narrative to address pastoral concerns, helping believers make sense of conflicts with Jewish communities while reinforcing the legitimacy of the Christian mission. For modern readers, these variants serve as a historical marker, revealing how theological priorities shaped the transmission of Scripture and inviting reflection on the complexities of interfaith dynamics in the early church.

2. Treatment of Women

The Western Text also reveals a distinct approach to women’s roles in the early church, often adjusting descriptions to align with the patriarchal norms of Greco-Roman society. These changes suggest that some communities sought to temper the prominence of women in the apostolic narrative, reflecting cultural expectations of the second century. In Acts 1:14, the standard text describes the disciples gathering “with the women and Mary the mother of Jesus” after the ascension, implying a significant role for women in the early Christian community. The Western Text, however, specifies that they gathered “with their wives and children,” a phrase that domesticates the women’s presence, framing them as family members rather than independent actors.[20].

In Acts 17:4, the standard text highlights the conversion of “a great many of the devout Greeks and not a few of the leading women” in Thessalonica, suggesting women of status joined the movement. The Western Text rephrases this to “a great many of the devout and Greeks and not a few of the wives of prominent men,” shifting the emphasis to their husbands’ status and diminishing the women’s independent agency. A similar pattern appears in Acts 17:12, where the Alexandrian text notes that “many Greek women of high standing as well as men” believed in Berea, listing women first. The Western Text rearranges this to “many of the Greeks and men and women of high standing believed,” placing men before women and grouping them as a single entity, thus reducing the prominence of female converts.[21]

Perhaps most notably, in Acts 17:34, the Western Text omits Damaris, a named female convert in Athens, from the list of those who joined Paul. This erasure is significant, as Damaris is one of the few named women in Acts, suggesting her importance in the early mission. Similarly, in Acts 18:26, the standard text lists “Priscilla and Aquila” as instructing Apollos, with Priscilla’s name first, implying her leading role. The Western Text reverses this to “Aquila and Priscilla,” aligning with conventional patriarchal ordering. These changes reflect a tendency to minimize women’s prominence, likely to conform to the social expectations of second-century Greco-Roman audiences. For modern readers, these variants highlight the cultural pressures that shaped early Christian communities and invite reflection on how gender roles have been interpreted across time.[22]

3. Enhanced Apostolic Authority

In contrast to its adjustments to Jewish opposition and women’s roles, the Western Text consistently elevates the authority and effectiveness of apostolic leaders, portraying them as bold, Christ-centered figures divinely empowered for their mission. This tendency reflects early Christian reverence for the apostles as foundational leaders, emphasizing their role in proclaiming the gospel amidst opposition. In Acts 16:4-5, for example, the standard text states that Paul and Timothy delivered the Jerusalem Council’s decrees to the churches. The Western Text expands this, noting that they did so “with all boldness to everyone, preaching the Lord Jesus Christ along with delivering the letter.” This addition underscores their fearless proclamation and missionary zeal, presenting them as unwavering ambassadors of Christ.[23]

Similarly, in Acts 28:31, describing Paul’s house arrest in Rome, the standard text notes that he taught “with all boldness and without hindrance.” The Western Text amplifies this, adding that he proclaimed Jesus as “the Christ, the Son of God, through whom the whole world will be judged.” This expansion introduces a strong Christological and eschatological emphasis, framing Paul’s teaching as a cosmic declaration of Jesus’ divine identity and authority. Such additions reflect the priorities of early Christian communities, who sought to highlight the apostles’ divine mandate and their role in establishing the church’s theological foundations.[24]

This enhancement of apostolic authority also appears in smaller details, such as Acts 18:8, where the standard text states that Crispus, the synagogue ruler, “believed in the Lord together with his entire household.” The Western Text adds that he did so “when he heard the teaching,” explicitly linking his conversion to Paul’s preaching and reinforcing the apostle’s persuasive power. These variants collectively portray the apostles as heroic figures, divinely guided to overcome obstacles and proclaim the gospel with clarity and conviction. For modern readers, these expansions offer a vivid picture of how early Christians viewed their leaders, inspiring contemporary reflection on the role of bold proclamation in ministry.[25]

Case Study: Barnabas and Jewish Exegetical Methods

The Western Text's treatment of Barnabas offers a striking example of how this tradition employs sophisticated Jewish exegetical techniques to create theological meaning. In this vein, Read-Heimerdinger argues that Codex Bezae contains a unique reference to Barnabas in Acts 1:23 that fundamentally changes our understanding of his role in the early church.[26]

The Acts 1:23 Variant

In Acts 1:23, where the Alexandrian text reads "Joseph called Barsabbas," Codex Bezae reads "Joseph called Barnabas." This variant, supported by several Old Latin manuscripts and other witnesses, identifies Barnabas as one of the two candidates proposed to replace Judas among the twelve apostles. Rather than being a scribal error, this reading reveals a carefully constructed theological narrative.

Typological Identification with the Patriarch Joseph

The Western Text deliberately associates Barnabas with the patriarch Joseph through multiple parallels: both are called "the righteous one," both serve as sources of comfort and encouragement to their communities, and both represent Jews living among foreigners. This typological identification follows traditional Jewish exegetical methods that view present events through the lens of biblical precedents, where "everything that happens in the history of the people of God is viewed as belonging to the whole."

Significance of Rejection

If Barnabas was indeed proposed as a replacement for Judas but not chosen, this creates a parallel with Joseph's rejection by his brothers. Read-Heimerdinger argues that Barnabas's rejection reflects the early community's reluctance to accept a Hellenistic Jew (from Cyprus) as equal to the Palestinian apostles, despite his superior qualifications. The conclusion drawn is that "the rejection of Barnabas is as misguided and unwarranted as the rejection of Joseph in the story of Genesis."

Implications for Understanding the Western Text

This analysis demonstrates several key features of the Western Text:

Sophisticated Jewish Perspective: The subtleness and intricacy of Jewish resonances and allusions mark the Western Text as "expressing its message from within Judaism" rather than from an outside Christian perspective.

Critical Portrayal of Early Leaders: Rather than presenting the apostles as infallible, the Western Text shows them as "learning and growing in understanding," making mistakes that require correction.

Methodological Consistency: The Barnabas analysis exemplifies how the Western Text employs "discreet allusion, with a word or a phrase used to evoke a whole scene or idea" rather than direct quotation.

Textual Priority Arguments

Based on the above, Read-Heimerdinger argues that the sophisticated Jewish interpretive framework in the Western Text suggests it preserves the original composition, as it would be difficult to explain why later Christian editors would invent such complex Jewish theological connections. The Barnabas material exemplifies this argument, requiring "extraordinary clarity of spiritual understanding in association with a thorough familiarity with a pre-Christian Jewish cultural and theological perspective."

Practical Applications: Enriching Ministry with Variants

For ministers and teachers, the Western Text is more than a scholarly curiosity—it’s a treasure trove for biblical instruction. When preaching on Acts 15, you might highlight how some early manuscripts frame the Apostolic Decree as an ethical call, resonating with modern congregations seeking universal principles. For example, you could say, “Early Christians emphasized ‘do not do to others what you would not want done,’ a principle that guides our relationships today.” In a Bible study on Peter’s prison escape, mentioning the “seven steps” helps listeners visualize the scene, grounding the miracle in a real place. Similarly, Paul’s teaching schedule in Acts 19:9 offers a glimpse into his strategic ministry, inspiring practical discussions about outreach in busy modern contexts.[27]

To incorporate variants effectively, introduce them naturally: “An early version of this passage adds a detail that deepens our understanding.” Focus on meaning rather than technicalities, using accessible language like “different early versions” instead of “text-types.” Connect variants to practical applications, such as using the Ethiopian eunuch’s confession to discuss the role of faith in baptism. These insights not only enrich teaching but also connect modern believers to the early church’s dynamic engagement with Scripture.[28]

The Western Text as an Evolving Tradition

The Western Text challenges simplistic views of how Scripture developed, revealing a gradual process where oral and written traditions intertwined. Many of its expansions reflect liturgical practices, such as the Ethiopian eunuch’s confession in Acts 8:37, which mirrors early baptismal formulas found in documents like the Apostolic Tradition. Others address pastoral needs, like Acts 16:35-39, where the Western Text explains the magistrates’ decision to release Paul and Silas by noting they “remembered the earthquake that had happened” and were afraid. This addition clarifies their motivations, aiding early teachers in explaining the narrative to congregations.[29]

Pasi Hyttinen’s 2019 “evolving text” theory reframes the Western Text as a tradition that developed through multiple stages of adaptation, not a single editorial act. Different communities shaped the text to address their theological and pastoral concerns, leading to variations among Western witnesses. For instance, some expansions appear in Codex Bezae but not in Old Latin manuscripts, reflecting diverse interpretive priorities. This perspective underscores that early Christians saw Scripture as a living tradition, authoritative in its apostolic message but flexible in its wording.[30]

This view reshapes our understanding of biblical authority. The substantial agreement across textual traditions in essential content demonstrates early Christians’ commitment to faithful transmission. Yet their willingness to clarify and expand suggests they prioritized the message over verbatim precision, inviting modern readers to approach Scripture with humility and openness to its community-shaped nature.[31]

Conclusion: The Western Text as a Living Voice

The Western Text of Acts isn’t just a collection of oddities or additions—it’s a powerful reminder of how Scripture was received, shaped, and lived out by early Christian communities. These unique readings—whether it’s the Ethiopian eunuch’s confession or the more universal tone of the Apostolic Decree—offer real insight into how believers in the second century were trying to follow Jesus in their world.

Recent scholarship has helped us look at these differences in new ways. Tools like the CBGM are moving the conversation beyond labels like “corrupt” or “authentic,” encouraging us to evaluate each variant on its own terms. And the ongoing debate between Read-Heimerdinger and Dawson shows just how vibrant this field still is. While Read-Heimerdinger sees the Western Text as preserving early, possibly Jewish-Christian traditions, Dawson pushes back, arguing these readings often reflect theological reshaping rather than historical priority. Together, they keep the conversation open and thoughtful.

So what does this mean for us?

Preach with depth: These textual variations aren’t just historical footnotes—they’re rich narrative choices that can expand the way we engage Scripture from the pulpit. When the Western Text adds dialogue or shifts emphasis, it can highlight theological themes or pastoral insights that might otherwise go unnoticed. Use them to bring familiar passages to life and to help listeners feel the dynamic way early Christians were working out their faith.

Teach with transparency: Whether you're leading a Bible study or teaching in a classroom, be honest about how the New Testament came together. Show your community that the process wasn’t mechanical, but deeply human and Spirit-led. Introducing tools like CBGM or the differences between text forms can build trust—not confusion—when handled well. It reassures learners that asking questions doesn’t threaten the Bible’s authority; it deepens our appreciation for its history.

Engage with curiosity: You don’t have to be a scholar to enter this conversation. Read-Heimerdinger and Dawson don’t agree—and that’s okay. Their dialogue shows us that it's possible to explore bold ideas, challenge long-held assumptions, and still remain committed to the text. Following their example, we can model a faith that doesn’t retreat from complexity, but leans into it with openness, humility, and a desire to learn.

The Western Text reminds us that the Bible was never just written—it was lived, debated, and handed down in community. By taking these differences seriously, we’re not weakening Scripture—we’re honoring the very process that helped shape it. And we’re stepping into a long tradition of believers who wrestled with the Word, trusted its message, and let it transform their lives.

References

[1]: Bruce Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1994), 222-236, https://www.amazon.com/Textual-Commentary-Greek-Testament-Ancient/dp/1598561642.

[2]: D.C. Parker, Codex Bezae: An Early Christian Manuscript and its Text (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 35-49, https://www.cambridge.org/us/universitypress/subjects/religion/biblical-studies-new-testament/codex-bezae-early-christian-manuscript-and-its-text.

[3]: Eldon Epp, “Traditional ‘Canons’ of New Testament Textual Criticism: Their Value, Validity, and Viability,” in The Textual History of the Greek New Testament, eds. K. Wachtel and M.W. Holmes (Atlanta: SBL, 2011), 79-127, https://brill.com/edcollbook/title/20983.

[4]: C.K. Barrett, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1998), 734-737, https://www.logos.com/product/4157/acts-vol-2.

[5]: Richard I. Pervo, Acts: A Commentary (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2009), 302-303, https://www.fortresspress.com/store/product/9780800660451/Acts.

[6]: Eckhard J. Schnabel, Acts, Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2012), 787-788, https://zondervanacademic.com/products/acts1.

[7]: F.F. Bruce, The Book of the Acts, New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988), 177-178, https://www.eerdmans.com/9780802825056/the-book-of-the-acts/.

[8]: Ben Witherington III, The Acts of the Apostles: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 387, https://www.eerdmans.com/9781467429580/the-acts-of-the-apostles/.

[9]: Friedrich Blass, Acta Apostolorum sive Lucae ad Theophilum liber alter (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1895), 7-29, https://www.amazon.com/Apostolorum-Lucae-Theophilum-Liber-Alter/dp/B07QZL762C.

[10]: B.F. Westcott and F.J.A. Hort, The New Testament in the Original Greek (Cambridge: Macmillan, 1881), 120-126, https://www.amazon.com/New-Testament-Original-Greek/dp/1602067759.

[11]: Bruce M. Metzger and Bart D. Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 4th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 315-318, https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-text-of-the-new-testament-9780195161229.

[12]: Jenny Read-Heimerdinger and Josep Rius-Camps, The Message of Acts in Codex Bezae: A Comparison with the Alexandrian Tradition, 4 vols. (London: T&T Clark International, 2004-2009), https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/bezan-text-of-acts-9780826462121/.

[13]: David C. Parker, An Introduction to the New Testament Manuscripts and Their Texts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 172-175, https://assets.cambridge.org/97805218/95538/frontmatter/9780521895538_frontmatter.pdf.

[14]: Klaus Wachtel, “Colwell Revisited: Grouping New Testament Manuscripts,” in The New Testament in Early Christianity: Proceedings of the Lille colloquium, July 2000, ed. C.B. Amphoux and J.K. Elliott (Lausanne: Editions du Zebre, 2003), 31-43, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25442490.

[15]: Read-Heimerdinger and Rius-Camps, The Message of Acts in Codex Bezae.

[16]: Zachary Dawson, “The Textual Traditions of Acts: What Has Discourse Analysis Contributed?” Biblica 100:4 (2019): 560-583, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48567984.

[17]: Eldon Jay Epp, “Anti-Judaic Tendencies in the D-Text of Acts: Forty Years of Conversation,” in The Book of Acts as Church History, eds. T. Nicklas and M. Tilly (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2003), 111-146, https://www.amazon.com/Book-Church-History-Apostelgeschichte-Kirchengeschichte/dp/311017717X.

[18]: Ibid.

[19]: Ibid.

[20]: Marg Mowczko, “Anti-Woman Tendencies in Codex Bezae,” MargMowczko.com, 2021, https://margmowczko.com/anti-woman-tendencies-in-codex-bezae/.

[21]: Ibid.

[22]: Ibid.

[23]: Mikeal C. Parsons, Acts, Paideia Commentaries on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 366-367, https://bakerpublishinggroup.com/books/acts/279190.

[24]: Ibid.

[25]: Ibid.

[26]: Jenny Read-Heimerdinger, "Barnabas in Acts: A Study of His Role in the Text of Codex Bezae," JSNT 72 (1998): 23-66.

[27]: Harry Y. Gamble, Books and Readers in the Early Church: A History of Early Christian Texts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 142-144, https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300069181/books-and-readers-in-the-early-church/.

[28]: Gordon D. Fee and Mark L. Strauss, How to Choose a Translation for All Its Worth (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2007), 110-111, https://zondervanacademic.com/products/how-to-choose-a-translation-for-all-its-worth.

[29]: Paul F. Bradshaw, Early Christian Worship (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2010), 28-30, https://litpress.org/Products/3366.

[30]: Pasi Hyttinen, “Evolving Gamaliel Tradition in Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis, Acts 5:38-39,” Novum Testamentum 61:4 (2019): 386-410, https://helda.helsinki.fi/server/api/core/bitstreams/b1d28eee-c68b-4157-91f1-ffd0a2c3c87c/content.

[31]: William A. Graham, Beyond the Written Word: Oral Aspects of Scripture in the History of Religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 117-118, https://www.cambridge.org/us/universitypress/subjects/religion/religion-general-interest/beyond-written-word-oral-aspects-scripture-history-religion.

Frequently Asked Questions on the Western Text of Acts

Q1. What makes the Western Text of Acts different from other versions?

The Western Text, preserved primarily in Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis, expands the Book of Acts by 8% to 10% compared to standard Alexandrian manuscripts like Codex Sinaiticus. It includes vivid narrative details, theological clarifications, and pastoral adaptations across 494 unique passages. These additions transform the narrative into something more cinematic and contextual, often reflecting the needs and experiences of early Christian communities.

Q2. Is the Western Text considered more authentic or less reliable than other manuscripts?

This remains debated. Traditional scholarship viewed the Western Text as a secondary, embellished version. However, modern approaches—especially those using the Coherence-Based Genealogical Method (CBGM)—evaluate variants individually. Scholars like Jenny Read-Heimerdinger argue the Western Text may preserve early Jewish-Christian traditions and authorial coherence, while others like Zachary Dawson caution that its theological shifts suggest later redaction.

Q3. What are some key theological or narrative additions in the Western Text?

Notable expansions include. First, the Ethiopian eunuch’s confession in Acts 8:37 (“I believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God”), mirroring early baptismal liturgies. Second, a universal ethics framing of the Apostolic Decree (Acts 15), replacing ritual laws with the negative Golden Rule. Third, architectural details like “the seven steps” in Peter’s escape (Acts 12:10), adding historical texture. These variants often clarify characters’ motivations, enhance apostolic authority, and reflect cultural tensions within the early church.

Q4. How does the Western Text portray women and Jews differently than other versions?

The Western Text tends to portray character groups in different ways. First, it minimizes women’s prominence, often domesticating or omitting female figures (e.g., replacing “leading women” with “wives of prominent men”; omitting Damaris). Second, intensify Jewish opposition, using harsher rhetoric (e.g., “blaspheming” Jews in Acts 13:45) to heighten conflict between Jews and early Christians. These shifts reflect second-century concerns and cultural pressures, illustrating how early Christians shaped the text for their contexts.

Q5. Why should modern pastors or teachers care about the Western Text of Acts?

The Western Text isn’t just a scholarly curiosity—it offers rich resources for biblical teaching and preaching. Its vivid expansions, ethical emphases, and liturgical echoes (e.g., baptismal confessions) provide fresh angles for sermons and studies. When used thoughtfully, these variants can connect today’s readers to the dynamic, lived faith of the early church and underscore the human and communal shaping of Scripture.

Podcast Episode: Re-reading Luke-Acts' Characterization in Codex Bezae (Part 2) | Interview with Jenny Read-Heimerdinger