Ending That Begins: How Acts 28:30-31 Closes and Opens the Christian Story

This analysis challenges frustration with Acts' "abrupt" ending. Luke didn't fail to finish his story—he executed a sophisticated literary strategy. Paul's Roman house arrest isn't narrative incompleteness but theological triumph: the Word reaches "the ends of the earth" and continues "without hindrance" despite imperial constraints. Modern scholars now recognize Acts ends by beginning, transforming readers from passive observers into active participants. The perceived "problem" was interpretive, not authorial—expecting biographical closure instead of literary invitation. Paul's final citation of Isaiah 6:9-10 provides prophetic framework for understanding Jewish rejection as divine strategy rather than failure. Acts 28:31 launches readers into the unfinished drama of early Christian witness.

Greg Camp and Patrick Spencer

7/17/202546 min read

NOTE: This article was research and written with the assistance of AI.

Key Takeaways

Literary sophistication over narrative failure: Luke's "abrupt" ending represents deliberate theological achievement rather than editorial incompetence, employing sophisticated ancient historiographical techniques to create completion without closure, transforming apparent biographical gaps into invitations for ongoing reader participation in the Christian mission.

The Word as protagonist: C. Kavin Rowe's analysis reveals that divine speech (λόγος), not Paul or any human character, serves as Acts' true protagonist, with the climactic "without hindrance" (ἀκωλύτως) demonstrating both external triumph over imperial constraints and Paul's internal theological resolution regarding the Jewish-Gentile mission dynamic.

Prophetic vindication through Isaiah 6:9-10: Paul's final citation of Isaiah's hardening passage functions not as bitter denunciation but as prophetic vindication, confirming that Jewish rejection serves God's strategic plan to provoke eventual Jewish jealousy through Gentile success, preserving hope within apparent judgment while advancing universal salvation.

Hermeneutical invitation for contemporary application: Acts 28:30-31 positions modern readers as "Acts 29" participants continuing Luke's narrative through faithful community formation, bold testimony, and inclusive hospitality, demonstrating how ancient texts serve ongoing theological reflection rather than merely historical curiosity, with practical implications for church identity, mission strategy, and cultural engagement.

Ending That Begins: How Acts 28:30-31 Closes and Opens the Christian Story

"And he lived there two whole years at his own expense, and welcomed all who came to him, proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance" (Acts 28:30-31). These final words of Acts have puzzled and frustrated readers for nearly two millennia. Where is the dramatic conclusion to Paul's story? What happened to his trial before Caesar? Did he live or die, triumph or suffer defeat? The silence is deafening—and deliberate.

For centuries, biblical scholars treated Acts' abrupt ending as a literary problem requiring explanation. Lost manuscripts, authorial ignorance, apologetic evasion, or simple narrative incompetence—each theory attempted to solve what appeared to be Luke's failure to finish his story properly. Yet a growing scholarly consensus recognizes that Acts 28:30-31 represents not narrative failure but theological triumph, not incomplete storytelling but masterful literary strategy.

Recent interdisciplinary scholarship has revolutionized understanding of Luke's narrative strategy by integrating literary analysis with historical investigation and reader-response criticism. This comprehensive approach reveals that Acts' conclusion emerges not from editorial accident but from deliberate theological purpose—demonstrating how the Word of God reaches "the ends of the earth" and continues "without hindrance" into the reader's present moment. The convergence of historical-critical analysis, narrative criticism, and reader-response theory provides unprecedented insight into how Luke crafted his two-volume work as both historical account and ongoing invitation. From C. Kavin Rowe's analysis of the Word as protagonist to comparative studies with ancient historiography and epic literature, contemporary scholarship demonstrates that Luke's ending achieves completion precisely by refusing closure—finishing his story by launching readers into theirs.

This article examines how Acts 28:30-31 functions as a deliberate literary hinge that simultaneously concludes major narrative threads while opening new possibilities for reader participation in the Christian mission. Through analysis of historical contexts, narrative strategies, and interpretive frameworks, we discover how Luke's "ending that begins" speaks powerfully to contemporary concerns about religious authenticity, social transformation, and ongoing witness in an ever-changing world.

How the Ending of Acts Completes Paul's Makeover | Dr. Thomas E. Phillips | Ep. 6

The "Problem" of Acts' Ending: Setting the Scholarly Stage

Traditional Explanations and Their Limitations

The perception that Acts ends "abruptly" or "incompletely" has dominated scholarly discussion since the early church period, generating numerous theories that attempt to explain what appears to be Luke's editorial failure. These traditional explanations, while reflecting genuine literary concerns, often reveal more about modern expectations for narrative closure than about ancient storytelling conventions.[1]

The lost conclusion hypothesis represents the oldest attempted solution, tracing back to early patristic speculation about missing manuscript material. Some early church fathers suggested that Luke originally composed a longer ending that detailed Paul's fate but that this material disappeared through scribal error or persecution-related destruction.[2] However, manuscript evidence provides no support for this theory, and the consistent ending across all textual traditions suggests Luke intended precisely the conclusion we possess.

The ignorance theory gained prominence among historical-critical scholars who argued that Luke simply didn't know what happened to Paul and therefore ended his narrative where his knowledge terminated. This explanation treats Acts as straightforward historical reporting constrained by available sources rather than as carefully crafted theological literature.[3] F.F. Bruce, while supporting an early date for Acts, argued that Luke "stopped where his knowledge ended" but nevertheless "crafted a fitting close" that emphasized gospel triumph even under imperial constraints.[4] Yet this view underestimates Luke's literary skill, ignoring how the author selectively shapes known events to convey theological truths rather than being limited by incomplete information.

Apologetic strategy explanations suggest Luke deliberately avoided narrating Paul's martyrdom to protect Christianity's legal standing within the Roman Empire. This theory positions Acts as propaganda designed to demonstrate Christian innocence and Roman tolerance rather than honest historical reporting.[5] I. Howard Marshall and Craig Keener have argued that ending during house arrest showcases Roman authorities finding no fault in Paul, thereby portraying Christianity as a legally tolerable movement rather than a subversive threat.[6] While this highlights Luke's political nuance, it risks reducing the text to mere defense, overlooking the broader theological invitation embedded in the open ending.

Historical termination theories propose that Luke wrote Acts before Paul's trial concluded, making narrative resolution impossible because the events hadn't yet occurred. J.A.T. Robinson famously argued for a composition date around 62 CE, suggesting that Acts ends abruptly because Paul was still alive and his fate remained unknown.[7] This approach treats the ending as circumstantial accident rather than literary choice, neglecting evidence of Luke's intentional thematic arcs that reach fulfillment regardless of unresolved personal details.

Each of these traditional explanations shares a common assumption: that Acts' ending represents some form of narrative deficiency requiring external explanation. Whether attributed to lost sources, limited knowledge, strategic evasion, or historical timing, these theories treat Luke's conclusion as failure to achieve proper closure rather than success in accomplishing his intended purpose. By focusing on perceived gaps, they often miss how Luke's design prioritizes theological depth over biographical completeness, inviting readers to reflect on the implications for their own interpretive engagement.

Modern Scholarly Consensus

Contemporary biblical scholarship has increasingly challenged the assumption that Acts ends inadequately, recognizing instead that Luke's conclusion reflects deliberate literary and theological choices consistent with ancient historiographical conventions. This interpretive shift represents a fundamental reorientation from treating the ending as problem requiring solution to understanding it as achievement deserving analysis.[8]

Recognition of deliberate literary choice emerges through comparative analysis with other ancient works that employ similar open-ended conclusions to achieve specific rhetorical effects. Clare K. Rothschild's examination of Acts within ancient historiographical traditions demonstrates how Luke employs "authentication devices" common to Hellenistic historians, including deliberate use of open endings to establish narrative credibility and invite reader engagement.[9] Rather than failing to achieve closure, Luke succeeds in employing sophisticated literary techniques to accomplish his theological purposes.

Understanding ancient genre expectations reveals how modern demands for biographical resolution reflect contemporary rather than ancient literary conventions. Ancient historiography, unlike modern biography, prioritized theological and moral instruction over comprehensive life narratives. Loveday Alexander's analysis positions Acts within popular prose traditions that emphasized practical wisdom and community formation rather than individual fate.[10] This generic framework explains why Luke focuses on the Word's triumph rather than Paul's personal destiny, ensuring his narrative resonates with his original audience while conveying timeless truths.

The theological versus biographical priority distinction illuminates how Luke's interests transcend individual biography to address broader questions about divine action and community mission. Robert Tannehill's narrative unity studies demonstrate how Luke constructs his two-volume work to emphasize theological themes—the fulfillment of divine promises, the inclusion of Gentiles, and the unstoppable advance of God's word—rather than biographical completeness.[11] From this perspective, Paul's personal fate becomes secondary to the larger story of God's redemptive purposes, allowing interpreters to see the ending as a culmination of these themes rather than an incomplete personal arc.

Archaeological and historical validation supports Luke's historical reliability while confirming his selective emphasis on theologically significant events. Colin J. Hemer's detailed analysis of Acts' historical accuracy demonstrates remarkable knowledge of first-century political, social, and geographical details while acknowledging Luke's theological shaping of his materials.[12] This combination of historical accuracy and theological purpose suggests conscious literary strategy rather than ignorance or deception, bolstering confidence in Luke's intentionality and showing how he weaves fact with faith to create a compelling narrative.

The emerging scholarly consensus recognizes Acts' ending as sophisticated literary achievement that accomplishes Luke's theological objectives through deliberate narrative choices. Rather than failing to provide closure, Luke succeeds in creating completion—fulfilling his narrative purpose while inviting ongoing reader participation in the story he has begun. This consensus not only resolves past debates but also opens the text to fresh applications in contemporary theological reflection and ministerial practice.

Comparative Perspectives: Major Scholarly Approaches

Historical-Critical and Social-Scientific Integration

Historical-critical methodology has dominated Acts scholarship for over two centuries, generating significant insights into the text's composition, sources, and historical background while sometimes obscuring literary and theological dimensions that contribute to contemporary interpretation. Understanding this scholarly tradition provides essential context for evaluating recent interpretive developments.[13]

Hans Conzelmann's epochal periodization represents the most influential historical-critical interpretation of Acts, arguing that Luke divides salvation history into three distinct periods—Israel, Jesus, and the Church—with Acts documenting the emergence of the church age as response to delayed parousia expectations.[14] Conzelmann's "early Catholicism" thesis suggests that Luke's ending reflects institutional development rather than eschatological anticipation, positioning Acts within second-century church concerns rather than first-century apostolic experience, though this has been nuanced by later scholars who argue for a more integrated view of Luke's theology.[15]

Redaction criticism and theological shaping illuminates how Luke adapts his sources to serve distinctive purposes, revealing the author's intentional editorial choices that emphasize certain theological motifs over raw historical data.[16] Source criticism and the "we passages" discuss eyewitness testimony and editorial construction, exploring sections where the narrative shifts to first-person plural as possible indicators of direct participation or literary device.[17] Dating controversies and historical reliability affect interpretation, with debates centering on whether Acts was composed before or after Paul's death, influencing views on Luke's knowledge of events and his theological emphases.[18] Archaeological validation and social context enriches understanding by confirming Luke's detailed knowledge of first-century Mediterranean life, from urban structures to legal practices, supporting the narrative's historical plausibility while highlighting how Luke uses accurate settings to underscore theological points.[19]

Social-scientific approaches to Acts have enriched scholarly understanding by applying anthropological, sociological, and economic theories to illuminate the social dynamics and cultural contexts that shaped early Christian development. These methodologies provide important insights into how Luke's ending reflects realistic social circumstances and ongoing community needs.[20]

Cultural anthropology and Mediterranean values illuminate how honor-shame dynamics, kinship relationships, and patron-client arrangements affected early Christian community formation and mission strategy. Bruce Malina's social-scientific analysis demonstrates how understanding these cultural patterns enhances appreciation for Luke's narrative choices and contemporary applications.[21] Economic analysis and class relationships reveal how early Christian communities navigated questions of wealth, poverty, and social status within highly stratified ancient Mediterranean societies, with the reference to Paul's economic independence reflecting strategies for autonomy that allowed missionaries to avoid compromising dependencies while modeling equitable sharing.[22]

Urban sociology and community formation explains how Christianity spread most rapidly in cities, where diverse populations, existing social networks, and commercial connections created optimal conditions for religious innovation and expansion.[23] Gender analysis and women's participation reveals how early Christian communities created new opportunities for female leadership and involvement while operating within patriarchal social structures, with women playing significant roles that contributed to teaching and hosting, suggesting that Luke's silence on women in the Roman conclusion does not negate their likely presence but reflects broader patterns of empowerment.[24] Conflict resolution and community boundaries emerge as key issues for maintaining health in early Christian groups, as they sought to establish identity while engaging with diverse cultural and religious contexts, with mechanisms like the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15) modeling negotiation and inclusion.[25] Network analysis and social capital explains how early Christian expansion relied upon existing relationships and social connections rather than isolated efforts, turning personal ties into conduits for faith transmission and illustrating why Paul's "welcoming all who came" represents a hub in a larger web of connections.[26]

Literary-Critical and Theological Integration

Literary-critical approaches have revolutionized Acts scholarship by attending to narrative structure, rhetorical strategy, and theological artistry that previous methodologies often overlooked. These interpretive methods reveal how Luke achieves sophisticated theological objectives through careful attention to literary form and artistic technique.[27]

Narrative criticism and story structure demonstrates how Luke constructs his two-volume work to achieve both aesthetic satisfaction and theological instruction through carefully developed character relationships, plot progression, and thematic integration. Robert C. Tannehill's analysis of narrative unity reveals how Acts' ending functions within the larger story Luke tells rather than standing as isolated conclusion, emphasizing recurring motifs like divine guidance and community growth that build toward a cohesive message of unstoppable mission.[28] This approach uncovers how Luke weaves individual episodes into a grand arc, where the open ending serves as a climactic invitation for readers to enter the plot.

Rhetorical analysis reveals how Luke uses traditional techniques to influence his audience. Mikeal Parsons' rhetorical study demonstrates how Acts' conclusion employs deliberate strategies to create closure without resolution, satisfaction without completion, using devices like amplification and irony to persuade readers of the gospel's enduring power amid uncertainty.[29] Intertextuality and biblical theology show that Luke builds his narrative using Hebrew Bible traditions, Gospel sources, and early Christian writings to form a new theological synthesis responsive to both past and present concerns. Richard Thompson's intertextual analysis demonstrates how Acts' ending resonates with broader biblical themes while maintaining distinctive emphases, such as echoing prophetic promises of restoration to underscore the continuity between Israel's story and the church's global expansion.[30] Reader-response criticism and interpretive participation investigates how texts create meaning through reader engagement rather than merely containing predetermined significance that interpretation discovers, explaining why Acts' ending generates ongoing discussion and diverse applications as readers project their contexts onto the open conclusion.[31]

Genre criticism and literary conventions provides comparative context for understanding how Acts relates to other ancient literature while serving distinctive Christian theological purposes. Loveday Alexander's analysis positions Acts within popular ancient prose traditions while acknowledging unique theological contributions that distinguish Christian literature from purely secular writings, such as blending historiographical accuracy with epic-like themes of heroic witness and divine intervention.[32] Postcolonial criticism explores how Luke's narrative interacts with Roman imperial ideology, highlighting both adaptation and resistance in Christian responses to political authority and illuminating contemporary applications for Christian communities facing various forms of political constraint or cultural pressure.[33]

Theological interpretation of Acts emphasizes the text's continuing significance for Christian faith and practice while maintaining appropriate attention to historical and literary dimensions that inform contemporary application. These approaches demonstrate how biblical scholarship serves church life and spiritual formation.[34] Systematic theology uses Acts to inform modern Christian views on revelation, salvation, church, and mission, with the ending's emphasis on divine sovereignty and unstoppable word providing foundation for theological reflection on God's relationship to human history and cultural development.[35] Missional theology and contemporary application explores how Acts' conclusion informs current understanding of Christian witness, church identity, and global mission responsibility, with the geographic progression from Jerusalem to Rome and the emphasis on inclusive community providing biblical foundation for contemporary missional engagement.[36] Pneumatology and spiritual discernment examines how Acts documents the Holy Spirit's role in enabling effective Christian witness and community formation, with the boldness and freedom that characterize Paul's Roman ministry illustrating pneumatological themes that remain relevant for contemporary spiritual formation.[37] Ecclesiology and institutional development investigates how Acts illuminates questions about church structure, leadership formation, and institutional sustainability that continue to challenge contemporary religious communities, with Luke's documentation of emerging organizational patterns providing biblical guidance while acknowledging cultural and historical differences.[38]

Historical and Social Contexts: The World Behind the Text

Paul's Roman Imprisonment and Early Christian Communities

The historical plausibility of Paul's Roman house arrest provides important context for understanding how Luke's narrative conclusion reflects both authentic first-century conditions and theological interpretation of those circumstances. Archaeological and literary evidence supports the basic accuracy of Luke's description while illuminating the social dynamics that enabled continued ministry despite legal constraints.[39]

Archaeological evidence for house arrest practices confirms that Roman legal procedures included various forms of custody that allowed significant freedom for defendants awaiting trial, particularly those with Roman citizenship and financial resources. The discovery of first-century Roman housing remains in various Mediterranean sites demonstrates how upper-class residences could accommodate both family life and semi-public activities.[40] Legal circumstances surrounding Paul's appeals process reflect the complexity of Roman judicial procedures and the significant delays that characterized imperial legal systems, where cases involving provincial appeals to Caesar often required years for resolution, creating extended periods of legal limbo for defendants.[41]

Social dynamics that facilitated ministry illustrate how Roman house arrest, rather than preventing Christian witness, actually created unique opportunities for sustained teaching and community formation. Jerome Murphy-O'Connor's studies of Pauline urban ministry demonstrate how household-based activities formed the backbone of early Christian expansion.[42] The enforced stability of house arrest, combined with Paul's financial ability to "welcome all who came to him," created ideal conditions for the intensive teaching ministry Luke describes. The household of faith concept emerges as crucial for understanding how Roman legal constraints paradoxically enhanced rather than hindered Christian mission, as Paul's rented quarters became a semi-public space where visitors could engage in extended religious discussion without the itinerant pressures that characterized his earlier missionary journeys.[43]

House church networks formed the backbone of early Christian expansion, providing both meeting spaces and social frameworks that enabled religious communities to develop within existing social structures. L. Michael White's archaeological analysis of early Christian meeting places demonstrates how converted households served as centers for worship, instruction, and community formation.[44] Patronage systems and financial support illuminate how figures like Paul could maintain independent ministries while serving broader community needs, with the reference to Paul living "at his own expense" (Acts 28:30) suggesting either personal resources or financial support from fellow Christians that enabled him to provide hospitality for visitors.[45] Urban ministry contexts explain why Christianity spread most rapidly in cities, where diverse populations, existing social networks, and commercial connections created optimal conditions for religious innovation and expansion, making Rome's position as imperial capital and cosmopolitan center ideal for the kind of diverse ministry Luke describes.[46]

Rome as Symbol and Reality

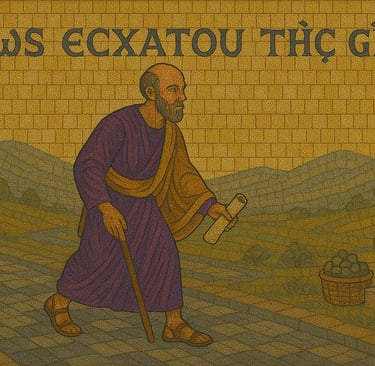

Rome's significance in Acts transcends mere geographical terminus to encompass symbolic, theological, and missiological dimensions that illuminate Luke's understanding of Christian witness within imperial contexts. The city's representation as both political center and spiritual destination reflects sophisticated theological reflection on the relationship between divine kingdom and earthly empire.[47]

Imperial significance as "ends of the earth" connects Luke's narrative conclusion with the programmatic statement of Acts 1:8, where Jesus promises that witnesses will reach "Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria, and to the ends of the earth." While "ends of the earth" could refer to various distant locations, Rome's position as imperial capital makes it the logical symbolic conclusion for a narrative emphasizing the gospel's universal scope.[48] Ben Witherington III's analysis demonstrates how Luke constructs his narrative geography to show Christianity penetrating the empire's heart rather than remaining on its periphery, transforming Rome from a seat of oppression into a stage for divine proclamation.[49]

Jewish-Christian relations in imperial context find their climactic expression in Paul's final synagogue confrontation (Acts 28:17-28), which recapitulates themes present throughout Luke-Acts while providing theological interpretation of Jewish resistance to Christian proclamation. Paul's quotation of Isaiah 6:9-10 (Acts 28:26-27) represents the fifth and final citation of this passage in the New Testament, offering biblical explanation for Jewish rejection while maintaining divine faithfulness to covenant promises.[50] Luke Timothy Johnson's analysis shows how this final Jewish-Gentile encounter in Rome symbolically represents the global scope of both Jewish diaspora and Christian mission, highlighting ongoing dialogue and tension that reflects real-world complexities of religious identity in a multicultural empire.[51]

Gentile mission culmination achieves its narrative climax with Paul's declaration that "this salvation of God has been sent to the Gentiles; they will listen" (Acts 28:28). This statement, delivered in Rome to both Jewish and Gentile audiences, represents the theological completion of the salvation-historical movement from Jerusalem to the nations.[52] Rather than rejecting Jewish election, Luke demonstrates how Gentile inclusion fulfills rather than replaces divine promises to Israel, challenging readers to consider how salvation extends beyond ethnic boundaries while fostering a theology of unity amid diversity.

The power dynamics of imperial witness reveal Luke's sophisticated understanding of how Christian testimony functions within systems of political authority. Paul's house arrest paradoxically demonstrates both Roman power and its limitations—Caesar can constrain Paul's movements but cannot silence his message.[53] This dynamic illustrates the complex relationship between divine sovereignty and human authority that characterizes Luke's political theology throughout Acts, serving as a model for believers navigating oppressive regimes through faithful presence rather than direct confrontation. Rome thus functions simultaneously as actual destination and symbolic representation of Gentile inclusion, imperial power, and universal scope, enabling Luke to ground his theological claims in historical reality while transcending merely local or temporal concerns.[54]

Narrative Threads: How the Ending Completes Luke's Story

Word as Protagonist and Geographic Fulfillment

C. Kavin Rowe's analysis fundamentally reframes understanding of Acts' ending by identifying the Word (λόγος) rather than any human character as the narrative's true protagonist. This insight transforms the apparent problem of Paul's unresolved fate into recognition of Luke's theological triumph—demonstrating how divine speech achieves victory even when human agents face constraints.[55] The theological centerpiece of Rowe's argument positions the Word of God as Acts' main character, whose growth and advance provide the narrative's central dramatic tension. Rather than focusing on individual apostolic careers, Luke constructs his story around the unstoppable progress of divine speech through human instrumentality.[56] This perspective explains why Luke can conclude his narrative with Paul under house arrest—the Word has achieved its objective regardless of Paul's personal circumstances.

The growth trajectory of the Word appears throughout Acts in carefully placed summary statements that mark major narrative developments while highlighting divine agency rather than human achievement. Rowe identifies the key progression: Acts 6:7 ("the word of God increased and the number of disciples multiplied greatly"); Acts 12:24 ("the word of God continued to spread and flourish"); Acts 19:20 ("the word of the Lord grew mightily and prevailed").[57] Each statement indicates divine initiative overcoming human obstacles, building cumulative momentum that culminates in the ending's affirmation of unhindered progress.

The Theological Significance of "Without Hindrance" (ἀκωλύτως)

The climactic declaration "without hindrance" (ἀκωλύτως) represents the narrative's theological conclusion, but scholarly analysis reveals this term functions on multiple interpretive levels that have been insufficiently explored in traditional scholarship.[58]

Traditional External Interpretation

The conventional scholarly interpretation presents ἀκωλύτως as demonstrating that external opposition—whether from Jewish rejection, Gentile hostility, or Roman imprisonment—cannot constrain the advance of God's kingdom.[59] This understanding emphasizes that Paul's physical chains paradoxically symbolize the unchained gospel. Despite being under house arrest, Paul continues his ministry "with all boldness and without hindrance," suggesting that no external force can ultimately thwart God's purposes.[60]

This interpretation finds strong support in the narrative progression of Acts, where the Word consistently overcomes obstacles: "the word of God increased and the number of disciples multiplied greatly" (Acts 6:7); "the word of God continued to spread and flourish" (Acts 12:24); "the word of the Lord grew mightily and prevailed" (Acts 19:20).[61] Each statement indicates divine initiative overcoming human obstacles, building cumulative momentum that culminates in the ending's affirmation of unhindered progress. C. Kavin Rowe's analysis demonstrates how these progressive statements position the Word as Acts' true protagonist, whose triumph provides the narrative's central theological achievement.[62]

Alternative Internal Resolution Interpretation

Recent scholarship, particularly influenced by analysis of Paul's theological development in Romans 9-11, suggests that "without hindrance" may indicate Paul's internal theological resolution regarding the Jewish-Gentile tension rather than merely freedom from external constraints.[63]

Paul's Theological Development: By Acts 28, Paul may have reached mature understanding of how the gospel spreads within the complex dynamics of Jewish-Gentile relations. Rather than being hindered by the need to continuously explain and convince resistant Jewish audiences, Paul has come to terms with the prophetic pattern established in Isaiah 6:9-10.[64] Joseph Tyson's analysis of the threefold pattern of Jewish rejection throughout Acts (13:46, 18:6, 28:28) demonstrates that each "turn to the Gentiles" was tactical rather than permanent, as Paul continues engaging Jewish audiences after each declaration.[65]

Strategic Clarity: The "without hindrance" description could reflect Paul's strategic acceptance that his primary calling was to the Gentiles, freeing him from internal tension over failed Jewish evangelism. This interpretation gains support from Paul's explicit statement in Romans 11:13-14 about magnifying his Gentile ministry to provoke Jewish jealousy.[66] Thomas Phillips' work on reading Acts within diverse frames of reference supports understanding Paul's mission strategy as theologically sophisticated rather than reactive.[67]

Pattern Recognition: Daniel Marguerat's narrative-critical analysis reveals that the threefold "turn to the Gentiles" pattern demonstrates repeated strategic responses rather than progressive escalation toward final Jewish rejection.[68] He notes that Luke presents "Christianity between Jerusalem and Rome" as the fulfillment of God's universal salvific plan that includes both Jews and Gentiles, with each rejection serving the larger divine purpose.[69]

Synthetic Understanding: Both External and Internal

Linda Maloney's contribution to the Wisdom Commentary provides crucial insight by connecting Acts 28 with Paul's theological framework in Romans 11.[70] Her analysis suggests that Acts 28 represents the narrative fulfillment of Paul's mature theology where:

Gentile success serves Jewish purposes: The flourishing Gentile mission is designed to provoke Jewish jealousy and eventual return (Romans 11:11)

Divine timing governs salvation: Paul has accepted that Jewish restoration will occur according to God's timeline, not through human persuasion alone

Calling clarity brings freedom: Understanding his primary apostolic calling to the Gentiles liberates Paul from the hindrance of constantly defending his message to resistant Jewish audiences[71]

Loveday Alexander's analysis of Acts within ancient literary conventions supports this interpretation, demonstrating how Luke employs open endings to establish narrative credibility and invite reader engagement rather than providing exhaustive biographical closure.[72]

The genius of Luke's conclusion lies in its theological comprehensiveness. The word ἀκωλύτως functions simultaneously as declaration of the gospel's triumph over external obstacles and testament to Paul's internal theological maturity regarding the Jewish-Gentile mission dynamic.[73] This reading transforms Paul's final imprisonment from merely a platform for continued evangelism into a theological culmination—the apostle to the Gentiles, finally free from both external constraint and internal tension, proclaiming the kingdom with complete clarity about his calling and confidence in God's ultimate purposes for both Jews and Gentiles.

The geographic progression from Jerusalem to Rome represents more than mere travel narrative; it embodies Luke's theology of salvation history and divine purpose unfolding through human witness across cultural, religious, and political boundaries. This spatial dimension demonstrates systematic theological reflection on the scope and direction of Christian mission.[74] The Jerusalem to Rome trajectory fulfills the programmatic promise of Acts 1:8 while reversing the traditional ancient Mediterranean understanding of Jerusalem as the world's center. Rather than nations coming to Jerusalem (as in Isaiah 2:2-4), Luke narrates the gospel going out from Jerusalem to reach the empire's heart.[75] This geographic reorientation reflects the transformed understanding of divine presence and purpose that characterizes Christian theology, challenging ethnocentric views and showing salvation radiating outward to all peoples.

Jewish-Gentile Relations and Leadership Transition

Luke's treatment of Jewish-Gentile relations throughout Acts reaches its climactic resolution in Paul's final encounter with Roman Jewish leaders (Acts 28:17-28), providing theological interpretation of Jewish resistance to Christian proclamation while maintaining divine faithfulness to covenant promises. This resolution demonstrates Luke's sophisticated approach to one of early Christianity's most challenging theological and practical issues.[76]

Enhanced Analysis of the Isaiah 6:9-10 Citation

The Isaiah 6 citation as theological explanation provides biblical warrant for understanding Jewish resistance as fulfillment rather than contradiction of divine purpose. Paul's quotation of Isaiah 6:9-10 (Acts 28:26-27) represents the fifth and final citation of this passage in the New Testament, following its use in Matthew 13:14-15, Mark 4:12, Luke 8:10, and John 12:40.[77] This prophetic text carries profound theological weight that requires careful unpacking to understand Luke's sophisticated theological strategy.

In Isaiah 6:9-10, the prophet receives a divine commission that appears paradoxical: "Go and tell this people: 'Keep on hearing, but do not understand; keep on seeing, but do not perceive.' Make the heart of this people dull, and their ears heavy, and shut their eyes; lest they see with their eyes, and hear with their ears, and understand with their hearts, and return and be healed."[78] This passage, spoken during Isaiah's temple vision (Isaiah 6:1-13), establishes a pattern where divine revelation simultaneously offers salvation and, when rejected, results in judicial hardening.

The Isaianic text functions on multiple levels: it describes the inevitable human response to divine revelation while maintaining divine sovereignty over historical outcomes.[79] Critically, the passage contains within itself both judgment ("make their hearts dull") and hope ("lest they...return and be healed"), suggesting that the hardening serves a larger redemptive purpose rather than representing final condemnation. This theological nuance becomes crucial for understanding Paul's deployment of the text in Acts 28.

Paul's deployment of Isaiah 6:9-10 in Acts 28:26-27 serves multiple theological functions that illuminate Luke's sophisticated understanding of Jewish-Gentile relations:[80]

Historical Continuity: The passage demonstrates that Jewish rejection was not unexpected but was prophetically anticipated. As Joseph Tyson observes, "all quotations of Isaiah 6:9-10 in the NT occur in the context of national Israel's unbelief in Jesus as Messiah," establishing a pattern of divine foreknowledge rather than divine failure.[81] This connection to broader biblical precedent transforms apparent failure into prophetic fulfillment.

Theological Framework for Understanding Rejection: Rather than attributing Jewish resistance to ethnic obstinacy or divine abandonment, the Isaiah citation provides scriptural interpretation that explains rejection as part of God's larger salvific strategy.[82] The prophetic text suggests that apparent "hardening" serves to open salvation to the Gentiles, which will ultimately provoke Jewish "jealousy" and lead to their inclusion (Romans 11:11-14). This framework preserves both divine sovereignty and Jewish hope within the narrative of temporary rejection.

Redemptive Purpose Within Judgment: The Isaianic framework maintains hope within judgment. The very structure of Isaiah 6:9-10—with its conditional "lest they...return and be healed"—preserves the possibility of restoration.[83] This theological nuance allows Paul to explain current Jewish rejection without foreclosing future Jewish inclusion, a theme developed extensively in Romans 9-11.

Linda Maloney's analysis in the Wisdom Commentary demonstrates how Acts 28 represents the narrative fulfillment of Paul's theological framework articulated in Romans 11.[84] The Isaiah citation functions not as bitter denunciation but as prophetic vindication—confirming that the pattern of Jewish rejection followed by Gentile acceptance represents divine strategy rather than human failure.

In Romans 11:13-14, Paul explicitly states his understanding: "Inasmuch as I am an apostle to the Gentiles, I magnify my ministry in order somehow to make my fellow Jews jealous, and thus save some of them."[85] This theological framework transforms the Isaiah 6 citation from a declaration of permanent hardening into an explanation of temporary strategic rejection that serves ultimate redemptive purposes. Daniel Marguerat's analysis supports this interpretation, noting that the Isaiah quotation functions as "prophetic rebuke rather than final rejection."[86]

This enhanced understanding of the Isaiah citation illuminates why Paul can minister "without hindrance" in Acts 28:31. Rather than being hindered by the need to continuously explain and convince resistant Jewish audiences, Paul has achieved theological clarity about his calling within God's larger plan.[87] The Isaiah citation provides biblical warrant for understanding that:

Jewish rejection was prophetically anticipated and therefore doesn't represent failure of divine promises

Gentile mission serves Jewish purposes by provoking the jealousy that will ultimately lead to Jewish restoration

Strategic focus on Gentiles represents obedience to divine calling rather than abandonment of Jewish hopes

The progression from apostolic to post-apostolic leadership represents a crucial but often overlooked dimension of Acts' narrative development, showing how Luke prepares readers for ongoing community life and mission after the foundational generation passes from the scene. This leadership transition provides important context for understanding why Luke concludes with Paul under house arrest rather than narrating his eventual martyrdom.[88] From Peter to Paul as central focus illustrates Luke's systematic approach to documenting how Christian leadership evolved from its initial Jerusalem base to encompass diverse cultural contexts and expanding geographic scope, with the narrative shift from Peter's prominence in early chapters to Paul's dominance in later sections demonstrating institutional development rather than individual biography.[89] From apostles to community structures emerges through Luke's attention to the development of organizational frameworks that enable Christian communities to function beyond dependence on founding figures, with examples like the selection of the Seven (Acts 6:1-7), the Jerusalem council (Acts 15), and the appointment of elders (Acts 14:23) illustrating institutional development that prepares communities for ongoing life and mission.[90]

The democratization of Christian witness becomes evident through Luke's documentation of how Christian testimony expands beyond apostolic figures to include diverse community members who participate in mission and ministry. The witness of Stephen, Philip, Apollos, Priscilla, and others demonstrates that effective Christian mission depends on community participation rather than individual leadership.[91] This preparation for the post-apostolic era explains why Luke concludes Acts during Paul's imprisonment rather than narrating his eventual martyrdom, demonstrating that Christian mission continues effectively even when primary leaders face constraints and providing encouragement for subsequent generations who will lack direct apostolic presence.[92]

Literary and Narrative Analysis: How the Ending Works

Completion vs. Closure and Ancient Literary Conventions

The fundamental distinction between completion and closure provides the interpretive key for understanding how Acts achieves its narrative purpose without satisfying conventional expectations for biographical resolution. This distinction, developed most clearly in C. Kavin Rowe's analysis, demonstrates how Luke accomplishes his theological objectives through sophisticated literary strategy rather than editorial failure.[93]

Closure refers to the psychological and aesthetic satisfaction that comes from resolving narrative tensions and answering outstanding questions about character fate and plot development.[94] Completion, by contrast, refers to the successful achievement of an author's stated or implied purposes, which may or may not include traditional forms of closure. Luke prioritizes the latter, fulfilling his thematic goals while leaving personal details unresolved.

Luke's achievement of narrative purpose becomes evident when Acts is evaluated according to the objectives Luke establishes in his prologue (Luke 1:1-4) and programmatic statements (Acts 1:8). Rather than promising biographical completeness or individual fate resolution, Luke commits to providing "an orderly account" of events and their theological significance.[95] The narrative completion occurs when the Word reaches Rome and continues "without hindrance," fulfilling the geographic and theological objectives Luke has established. This focus on divine mission over human story arcs satisfies the text's internal logic while encouraging readers to seek spiritual insight over mere biographical facts.

Understanding how Acts' conclusion relates to conventional patterns in ancient historiography, biography, and epic literature provides crucial context for evaluating Luke's achievement and recognizing his sophisticated use of established narrative techniques to accomplish theological purposes.[96] Ancient historiographical practices included various strategies for concluding narrative works that prioritized thematic completion over biographical exhaustiveness, with historians like Polybius and Josephus often employing open endings to emphasize ongoing historical processes rather than individual closure.[97] Rhetorical strategies of deliberate inconclusiveness appear throughout ancient literature as authors invite reader participation in determining narrative significance and contemporary application, transforming readers from passive consumers into active interpreters.[98]

Epic parallels with foundational narratives provide important comparative context for understanding how Luke constructs Acts as community-founding literature rather than individual biography. Marianne Palmer Bonz's analysis demonstrates striking parallels between Acts and Virgil's Aeneid, both of which narrate foundational journeys that establish new communities while ending with beginnings rather than conclusions.[99] The literary topos of the unfinished journey appears throughout ancient literature as authors demonstrate how significant movements transcend individual leadership to become ongoing historical forces, with Dennis R. MacDonald's mimesis criticism revealing how Acts 27-28 parallels Odyssean themes of dangerous voyage leading to new beginning rather than final homecoming.[100] Authentication devices in ancient historiography include summary statements, geographical markers, and thematic declarations that establish narrative credibility and interpretive framework, with Clare Rothschild's analysis demonstrating how Luke employs conventional historiographical techniques—including deliberate inconclusiveness—to establish his account's reliability while inviting ongoing engagement.[101]

Narrative Techniques and Intertextual Connections

Luke employs multiple sophisticated narrative techniques to achieve both literary artistry and theological instruction through his conclusion, demonstrating how skilled ancient authors integrated aesthetic achievement with didactic purpose. These techniques reveal the careful craftsmanship underlying what might appear to be simple narrative prose.[102]

Summarizing statements provide thematic closure without requiring biographical resolution, enabling Luke to demonstrate achievement while maintaining openness for continued development. The final verses (Acts 28:30-31) function as carefully constructed summary that encompasses key themes—boldness, teaching, universal welcome, and freedom from hindrance—while suggesting ongoing rather than completed activity.[103] Ironic reversal as theological commentary emerges through Luke's demonstration that apparent constraint produces expanded opportunity for witness and teaching, with Paul's house arrest creating ideal conditions for sustained instruction and relationship building rather than limiting ministry.[104]

Symbolic geography conveying theological meaning transforms concrete locations into representations of abstract spiritual realities, enabling Luke to ground theological claims in historical particularity while transcending merely local concerns. Rome functions simultaneously as actual destination and symbolic representation of Gentile inclusion, imperial power, and universal scope.[105] Temporal markers suggesting continuation indicate ongoing rather than concluded activity through Luke's careful use of verbal tenses and durational indicators, with the phrase "two whole years" establishing historical specificity while the present participles describing Paul's activities ("proclaiming," "teaching") suggest continuing rather than completed action.[106] Audience inclusion through universal language transforms Paul's specific Roman situation into paradigmatic example of Christian witness that transcends particular circumstances, with the phrase "all who came to him" suggesting both social inclusivity and narrative invitation for readers to participate in the welcoming community.[107]

The network of thematic and structural parallels between Acts' ending and other biblical texts, particularly within the Lukan corpus, demonstrates the author's sophisticated literary strategy and theological vision. These intertextual connections reveal how Luke constructs his narrative in dialogue with Scripture, enriching its depth and resonance.[108]

The Luke 24 parallel provides the most significant intertextual connection, showing how both volumes of Luke's work conclude with similar patterns of divine revelation, commission, and ongoing witness. Luke 24 ends with the disciples "continually in the temple blessing God" (Luke 24:53), while Acts concludes with Paul "proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ" (Acts 28:31).[109] Both endings emphasize worship and teaching as responses to divine revelation and commission, creating symmetry that unifies Luke-Acts and portrays the church as the continuation of Jesus' work.

Journey narrative symmetry reveals Luke's careful construction of parallel travel accounts that move in opposite geographic directions while maintaining similar theological purposes. Jesus' journey to Jerusalem (Luke 9:51-19:44) culminates in suffering, death, and resurrection that enable universal salvation, while Paul's journey to Rome (Acts 19:21-28:31) demonstrates how that salvation reaches "the ends of the earth" through witness.[110] Commission and fulfillment patterns connect Jesus' final instructions to his disciples (Luke 24:44-49; Acts 1:4-8) with the narrative demonstration of how those commissions find practical expression through apostolic mission, with the promise of power through the Holy Spirit (Acts 1:8) receiving fulfillment through the bold witness that characterizes Acts' conclusion.[111] These intertextual connections demonstrate Luke's sophisticated literary strategy for creating thematic unity across his two-volume work while achieving specific theological objectives through carefully constructed narrative parallels.

Reader-Response: The Ending as Invitation

From Theophilus to Contemporary Readers: The Expanding Circle of Interpretive Participation

While C. Kavin Rowe's hermeneutical framework emphasizes reader participation in determining contemporary significance, Luke's explicit dedication to Theophilus (Luke 1:3; Acts 1:1) provides important insight into how the ending functions as invitation rather than closure.[112]

Luke's explicit address to "most excellent Theophilus" establishes a primary intended reader while simultaneously creating space for secondary readership participation.[113] The name Theophilus, meaning "God-lover" or "friend of God," may function both as reference to a specific patron and as symbolic designation for any reader committed to understanding divine activity in human history.[114]

Alternative Approach to Theophilus via Codex Bezae: Jenny Read-Heimerdinger's research on Codex Bezae offers an alternative perspective that could significantly reshape our understanding of the Theophilus dedication. Working with Josep Rius-Camps, Read-Heimerdinger argues that Luke-Acts represents a unified "demonstration" to a specific Theophilus who was likely a Jewish authority figure—possibly even a high priest—requiring persuasion about the legitimacy of the Christian movement within Jewish tradition.[115] Her analysis of the Bezan text tradition suggests that Luke's purpose was not general historiography but targeted apologetic demonstration, designed to show a skeptical Jewish leader that Christianity fulfilled rather than contradicted Israel's scriptural expectations. This interpretation would transform the open ending of Acts from generic reader invitation into specific evidence presented to Theophilus (and subsequent readers) of God's ongoing faithfulness to Israel through the unstoppable advance of the Word among the nations.[116]

Historical Particularity with Universal Application: The Theophilus dedication demonstrates Luke's strategy of grounding his narrative in specific historical circumstances while crafting content that transcends particular limitations.[117] Just as Paul's house arrest represents both concrete historical reality and symbolic representation of the Word's triumph over constraint, the Theophilus address functions both as ancient epistolary convention and invitation for ongoing readership engagement. Loveday Alexander's analysis of the preface to Luke's Gospel demonstrates how this dedication follows classical historiographical conventions while serving distinctive Christian theological purposes.[118]

Incomplete Information as Interpretive Invitation: Luke's promise to provide Theophilus with "an orderly account...so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught" (Luke 1:3-4) establishes interpretive framework that prioritizes theological understanding over biographical completeness.[119] The "certainty" (ἀσφάλεια) Luke promises relates to divine faithfulness and the effectiveness of the apostolic mission rather than exhaustive historical detail. This interpretive priority explains why Luke can conclude Acts with Paul under house arrest—the theological certainty has been established regardless of unresolved biographical questions.

The transition from Theophilus as primary addressee to contemporary readers as interpretive participants reflects ancient literary conventions that enabled texts to transcend original circumstances while maintaining historical grounding.[120] Patron to Community: The Theophilus dedication likely reflects ancient patronage systems where wealthy individuals sponsored literary works that would subsequently circulate among broader communities.[121] This publication model anticipated expanding readership circles that would encounter the text in diverse circumstances requiring contextual application. Bruce Winter's analysis of early Christian benefaction patterns demonstrates how individual patronage served broader community formation and institutional support.[122]

Individual to Corporate Interpretation: While addressed to an individual, Luke-Acts clearly anticipates community readership engaged in collective discernment about identity, mission, and relationship to both Jewish heritage and Gentile inclusion.[123] The ending's emphasis on Paul welcoming "all who came to him" models the inclusive community formation that Luke envisions for his readers. This corporate dimension explains why Acts concludes with ongoing community activity rather than individual biographical resolution.

Understanding how the text moves from Theophilus to contemporary readers illuminates why Acts' ending functions as invitation rather than conclusion:[124] From Ancient to Modern "God-lovers": Contemporary readers who identify as "friends of God" (the meaning of Theophilus) inherit both the privilege and responsibility of determining ongoing significance of Luke's narrative.[125] The ending challenges modern "Theophiluses" to continue the story Luke has initiated. Daniel Marguerat's analysis of Luke as "the first Christian historian" demonstrates how the open ending serves specific narrative functions designed to engage readers in continuing the story rather than providing closure.[126]

From Individual Study to Community Formation: Just as the original Theophilus likely shared Luke's work with broader communities, contemporary readers bear responsibility for translating biblical interpretation into community formation and institutional engagement that reflects apostolic practices while addressing current circumstances.[127] This transformation from individual patron to community responsibility reflects Luke's understanding of how divine revelation serves corporate rather than merely personal purposes.

From Historical Information to Ongoing Participation: The "certainty" Luke promises Theophilus extends beyond historical accuracy to include confidence in divine faithfulness and the effectiveness of the apostolic mission.[128] Contemporary readers seek similar certainty through active participation in the ongoing story rather than passive consumption of ancient information. This participatory dimension explains why the ending emphasizes continuing ministry rather than concluded biography.

The Theophilus framework supports Rowe's emphasis on active readership versus passive consumption while providing historical grounding for contemporary application:[129] Interpretive Responsibility: Just as Theophilus received Luke's account with responsibility for understanding and application, contemporary readers inherit similar obligations for discerning significance and contemporary relevance.[130] This responsibility extends beyond individual spiritual formation to include community leadership and institutional engagement that continues the narrative Luke documents.

Community Accountability: The movement from individual patron to community readership establishes pattern for how personal biblical study serves corporate discernment and institutional engagement rather than merely individual satisfaction.[131] Kevin Vanhoozer's analysis of the drama of doctrine demonstrates how biblical interpretation serves community formation and cultural engagement through faithful performance of Scripture's ongoing story.[132]

Historical Continuity with Contemporary Application: The Theophilus model demonstrates how biblical interpretation honors historical particularity while embracing contemporary responsibility—maintaining connection to ancient testimony while engaging current challenges and opportunities.[133] This balance prevents both antiquarian irrelevance and anachronistic misapplication while enabling faithful contemporary interpretation.

This understanding transforms the question from "What happened to Paul?" to "How do we, as contemporary friends of God, continue the narrative Luke has begun?" The ending that appears to conclude with Theophilus actually begins with every subsequent reader who embraces both the privilege and responsibility of determining ongoing significance of God's unstoppable word.[134]

Hermeneutical Framework and Contemporary Application

C. Kavin Rowe's hermeneutical framework transforms traditional scholarly discussion of Acts' ending by repositioning it as deliberate invitation for reader participation in determining contemporary significance rather than providing predetermined answers to theological questions.[135] Active readership versus passive consumption distinguishes approaches to biblical interpretation that treat texts as sources of information versus invitations for ongoing reflection and application. Rowe argues that Acts' ending deliberately refuses to satisfy certain reader expectations in order to create space for contemporary audiences to wrestle with implications of the Word's triumph for their own contexts.[136] Participatory narrative structure emerges through Luke's construction of his conclusion as beginning rather than ending, requiring readers to consider how they might continue the story that Luke has initiated, with the narrative opening possibilities for ongoing interpretation and community formation that depend upon reader engagement and commitment.[137]

Theological reflection as interpretive responsibility challenges readers to determine what divine "victory" means within their particular historical and cultural circumstances. The declaration that Paul preached "without hindrance" raises questions about contemporary obstacles to Christian testimony and how divine sovereignty relates to human constraints in different social contexts.[138] The contemporary church as Acts 29 represents one influential application of Rowe's hermeneutical framework, suggesting that religious communities can understand themselves as continuing the narrative that Luke documents rather than merely studying historical events from distant past, transforming Acts from historical curiosity into contemporary commission and accountability.[139] Interpretive humility and ongoing discovery characterize the appropriate reader response to Luke's hermeneutical invitation, acknowledging that the meaning of Acts' ending continues to unfold through community discernment and practical application rather than being predetermined through scholarly analysis alone.[140]

The understanding of Acts' ending as hermeneutical invitation rather than narrative closure carries significant implications for how contemporary religious communities understand their identity, mission, and relationship to the biblical narrative. These ecclesial applications demonstrate how literary analysis serves practical theological reflection and community formation.[141] The church as continuing narrative emerges from recognition that Luke constructs his ending to position readers as participants in rather than merely observers of the story he documents, with religious communities that understand themselves as "Acts 29" recognizing responsibility for continuing the testimony and community formation that Luke describes while adapting to contemporary contexts and challenges.[142] Community responsibility as institutional calling extends beyond individual activity to encompass corporate commitment to embodying and proclaiming the theological insights that Jesus taught and Paul demonstrated, with the phrase "all who came to him" suggesting communities characterized by hospitality and inclusive welcome that reflects divine grace rather than human prejudice.[143]

Practical Applications for Scholarship and Interpretation

The recognition of Acts' ending as hermeneutical invitation rather than biographical conclusion provides rich opportunities for teaching and interpretation that connect ancient narrative with contemporary application while avoiding both antiquarian irrelevance and anachronistic misapplication.[144]

Academic frameworks can effectively present Acts' ending within broader theological contexts that help students understand both historical background and contemporary significance. A structured approach might address: (1) "The Word Unhindered"—exploring how divine speech transcends human constraints; (2) "Bold Testimony"—examining what courage means in various historical contexts; (3) "Universal Hospitality"—investigating how communities welcome diverse populations; and (4) "Ongoing Narrative"—challenging readers to understand their role in continuing the story Luke began.[145] Educational strategies for diverse audiences require careful balance to avoid either historical irrelevance or contemporary misapplication, with effective teaching demonstrating how understanding first-century circumstances illuminates rather than limits contemporary significance while maintaining awareness of both continuity and discontinuity between ancient and modern contexts.[146]

Cross-cultural perspectives and global Christianity enrich interpretation by providing insights from Christian communities experiencing social contexts that parallel ancient circumstances more closely than typical Western church experience. Voices from diverse cultural contexts, including those under political pressure and minority Christian communities, can illuminate aspects of Acts that may be invisible to interpreters from privileged social positions.[147] Academic study and intellectual formation emerge naturally from engagement with Acts' ending as communities consider what "boldness," "hospitality," and "unhindered" testimony mean within their particular contexts and challenges, with research methodologies, critical analysis, and comparative studies helping translate biblical interpretation into practical intellectual engagement.[148] Academic and liturgical applications provide opportunities for communities to embody the worship-learning integration that characterizes Acts' conclusion, with scholarly elements—research, critical reading, theological reflection, and comparative analysis—reflecting themes of divine sovereignty, institutional courage, and inclusive community that Luke emphasizes.[149]

Acts' conclusion provides practical guidance for intellectual development and scholarly formation that connects individual academic growth with community mission and cultural engagement. Academic mission and daily scholarship emerge from understanding how ordinary scholars participate in the ongoing advance of knowledge through faithful research, honest discourse, and practical service within their particular academic contexts and professional circumstances.[150] The household-based ministry Luke describes illustrates how authentic Christian scholarship often occurs through relationships and daily activities rather than formal programs, encouraging scholars to engage naturally in conversations and acts of intellectual service while extending the narrative through academic work. Intellectual formation and practical service require integration as individuals seek both personal growth in understanding and meaningful contribution to community welfare and social knowledge, with Paul's combination of intensive teaching and practical hospitality providing a model for holistic academic engagement that serves both individual development and community transformation.[151]

Theological Implications: What the Ending Teaches

Nature of God's Word and Church Mission

Acts' conclusion provides profound theological insight into the character and function of divine speech within human history, demonstrating how God's word operates with sovereignty and effectiveness that transcends human limitation and cultural constraint. This theological understanding provides foundation for contemporary reflection on revelation, Scripture, and ongoing divine communication.[152]

Divine power and unstoppable advance emerge as central characteristics of God's word throughout Acts, culminating in the triumphant declaration that Paul preached "without hindrance" despite apparent imperial constraint.[153] The Word's ability to overcome opposition, transcend cultural boundaries, and achieve divine purposes regardless of human circumstances reflects theological understanding of divine sovereignty over human history, offering assurance to contemporary readers facing societal or personal barriers that divine truth ultimately triumphs through persistence and providence.[154]

Divine presence through human testimony demonstrates how divine speech becomes historically effective through human instrumentality while maintaining its essential divine character and authority.[155] Faithful cooperation enables partnership, as exemplified by Paul's teaching ministry in Rome, where human vulnerability (house arrest) becomes the vessel for divine proclamation, echoing the incarnation of Christ and reminding believers that God's word is embodied in faithful human lives. Cross-cultural effectiveness and contextual adaptation reveal how God's word maintains essential content while achieving effective communication across diverse cultural and linguistic contexts, with the progression from Jewish to Gentile audiences throughout Acts demonstrating divine intention for universal communication while requiring human wisdom for appropriate contextualization.[156] Universal truth enables rather than prevents cultural sensitivity, providing a model for contemporary interpretation where core theological insights are translated into relevant contexts without dilution.

The understanding of Acts' ending as theological climax rather than narrative failure provides crucial insights into Christian ecclesiology that continue to inform contemporary reflection on church identity and purpose. These theological implications demonstrate how ancient texts provide guidance for ongoing community formation and institutional engagement.[157] Apostolic succession and institutional continuity emerge through Luke's documentation of how Christian mission continues beyond founding leadership while maintaining essential theological commitments and practical strategies, with the transition from apostolic to post-apostolic ministry illustrating how institutional development serves rather than replaces spiritual vitality and effective testimony.[158] Global vision and local application require integration as Christian communities recognize their participation in worldwide testimony while addressing particular cultural contexts and local challenges, with Acts' geographic progression from Jerusalem to Rome providing theological framework for understanding how local faithfulness serves universal purposes while avoiding both narrow parochialism and rootless universalism.[159]

Inclusive community and theological integrity present ongoing challenges as churches seek to embody radical hospitality while maintaining distinctive Christian identity and theological convictions. Paul's welcome of "all who came to him" illustrates how theological clarity enables rather than prevents inclusive community formation that transcends social, economic, and cultural boundaries.[160] Boldness and cultural engagement characterize authentic Christian testimony that maintains doctrinal distinctiveness while engaging effectively with diverse cultural contexts and challenging social circumstances, with the "boldness" that Luke emphasizes suggesting courage for both proclamation and practical service that may require risk-taking and creative adaptation to changing circumstances.[161] Worship and testimony integration demonstrates how authentic Christian spirituality encompasses both devotional practice and public engagement rather than treating these as competing priorities, with Acts' conclusion showing how teaching ministry, community formation, and spiritual growth function as complementary aspects of comprehensive Christian discipleship.[162]

Individual Calling and Contemporary Relevance

Acts' conclusion provides important insights into how individual Christians understand their participation in God's mission while maintaining appropriate emphasis on community formation and corporate testimony. These theological implications demonstrate how personal discipleship serves broader divine purposes rather than merely individual spiritual satisfaction.[163]

Personal testimony as community responsibility emerges through understanding how individual Christian witness contributes to broader patterns of community formation and cultural transformation that extend beyond personal activity, with Paul's household ministry illustrating how individual faithfulness enables community development that serves divine purposes in ways that transcend personal achievement.[164] Vocational integration and spiritual formation require ongoing reflection as individuals seek to understand how their particular skills, circumstances, and opportunities contribute to broader Christian mission while serving legitimate personal and family needs, with Paul's ability to maintain ministry while supporting himself financially providing example of how vocational responsibility and spiritual calling can function as complementary rather than competing priorities.[165]

Contextual ministry and cultural adaptation become necessary as individual Christians seek to communicate theological truth effectively within their particular social circumstances while maintaining theological integrity and spiritual authenticity. Paul's adaptation to house arrest constraints illustrates creative flexibility that serves faithfulness rather than compromising it.[166] Courage and cultural engagement emerge as essential characteristics for effective Christian testimony that requires willingness to address challenging social issues while maintaining respectful dialogue with diverse perspectives and religious traditions, with the boldness that characterizes Paul's Roman ministry suggesting courage for both proclamation and practical service that may involve personal risk.[167] Spiritual growth and practical service function as integrated aspects of Christian discipleship that serve both individual development and community formation, with Acts' emphasis on teaching ministry demonstrating how learning and service function as complementary activities that contribute to both personal formation and community development.[168]

The themes and challenges addressed in Acts' ending maintain striking relevance for contemporary religious communities facing questions about institutional identity, cultural engagement, and effective testimony. These connections demonstrate how ancient texts continue to provide insight and guidance for current challenges while respecting historical specificity.[169] Religious authenticity versus cultural accommodation presents ongoing challenges as communities seek to maintain theological integrity while engaging effectively with diverse cultural contexts. Paul's ability to minister within Roman imperial constraints provides example of how to navigate complex relationships between faith commitment and social participation.[170] Institutional constraints and legal restrictions may limit traditional ministry, but Paul's house arrest shows how obstacles can inspire innovation in teaching and outreach, with creative approaches to community formation addressing financial limitations, legal restrictions, and social pressures.[171]

Political engagement and social responsibility require careful theological reflection as communities consider how Christian testimony relates to contemporary issues of economic inequality, social reconciliation, and political responsibility. Acts' emphasis on inclusive community and bold testimony provides biblical foundation for social engagement while maintaining focus on spiritual transformation rather than mere activism.[172] Interfaith dialogue and religious diversity present opportunities and challenges as Christian communities encounter increasing pluralism, with Paul's engagement with Jewish leaders illustrating maintaining distinctiveness while acknowledging God's work in diverse communities.[173] Global mission and local testimony require integration as Christian communities recognize their responsibility for both local community engagement and global institutional participation, with Acts' geographic progression providing framework for understanding how local faithfulness serves universal purposes while avoiding both narrow parochialism and rootless cosmopolitanism.[174] Leadership development and institutional sustainability become crucial as established religious communities prepare for generational transition and cultural change, with Luke's documentation of emerging leadership structures and community formation providing biblical guidance for developing sustainable institutions that serve rather than supplant spiritual vitality and effective testimony.[175]

Endnotes

[1] Richard I. Pervo, Acts: A Commentary (Hermeneia; Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2009), 697-702.

[2] F.F. Bruce, The Acts of the Apostles: The Greek Text with Introduction and Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990), 544-548.

[3] Henry J. Cadbury, The Making of Luke-Acts (London: SPCK, 1958), 322-326.

[4] F.F. Bruce, New Testament History (Garden City: Doubleday, 1972), 415-420.

[5] I. Howard Marshall, The Acts of the Apostles (TNTC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980), 423-429.

[6] Craig S. Keener, Acts: An Exegetical Commentary (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2015), 4:3725-3741.

[7] J.A.T. Robinson, Redating the New Testament (London: SCM Press, 1976), 86-92.

[8] Troy M. Troftgruben, A Conclusion Unhindered: A Study of the Ending of Acts within Its Literary Environment (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), 15-45.

[9] Clare K. Rothschild, Luke-Acts and the Rhetoric of History: An Investigation of Early Christian Historiography (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2004), 275-298.

[10] Loveday Alexander, Acts in Its Ancient Literary Context: A Classicist Looks at the Acts of the Apostles (London: T&T Clark, 2005), 195-220.

[11] Robert C. Tannehill, The Narrative Unity of Luke-Acts: A Literary Interpretation (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1990), 2:344-363.

[12] Colin J. Hemer, The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1989), 383-410.

[13] William W. Gasque, A History of the Interpretation of the Acts of the Apostles (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1989), 21-43.

[14] Hans Conzelmann, The Theology of St. Luke (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1982), 149-169.

[15] Ibid., 162-169.

[16] Stanley E. Porter, The Paul of Acts: Essays in Literary Criticism, Rhetoric, and Theology (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1999), 10-34.

[17] Colin J. Hemer, The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History, 376-410.

[18] Craig S. Keener, Acts: An Exegetical Commentary, 1:258-392.

[19] Charles H. Talbert, Literary Patterns, Theological Themes and the Genre of Luke-Acts (Missoula: Scholars Press, 1974), 125-140.

[20] Bruce J. Malina, The New Testament World: Insights from Cultural Anthropology (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), 25-47.