Hospitable Barbarians: Luke’s Ethnographic Reversal in Acts 28:1–11

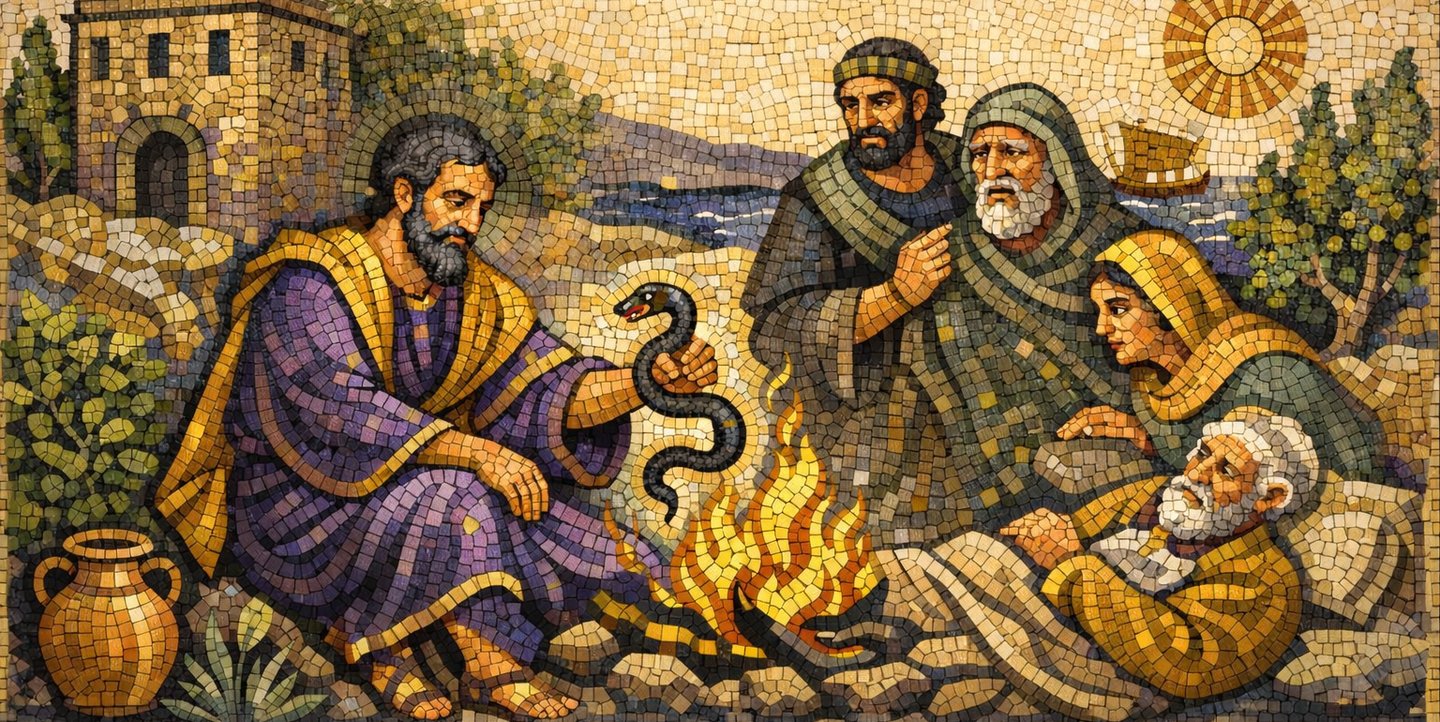

Luke’s Malta episode overturns ancient ethnic expectations by pairing the loaded label “barbarians” with striking kindness and moral clarity. Instead of the hostile islanders typically found in shipwreck narratives, the Maltese respond to 276 soaked, exhausted strangers with immediate care, warmth, and welcome. Their interpretation of Paul’s viper encounter shows not superstition but serious, coherent reasoning about justice and divine action. Publius’s formal guest-friendship and the island-wide healings deepen a reciprocal relationship that elevates the Maltese as exemplars of humane response. The narrative anticipates the wider Gentile openness that concludes Acts, insisting that genuine hospitality and moral insight—not cultural status or ethnic identity—reveal who is truly receptive to God’s presence, compassion, and active concern for all humanity, especially in moments of profound vulnerability.

Greg Camp and Patrick Spencer

12/17/202528 min read

NOTE: This article was researched and written with the assistance of AI.

Key Takeaways

1. Luke Uses “Barbarians” to Challenge Ethnic Stereotypes. Luke intentionally employs the loaded term βάρβαροι to activate Greco-Roman expectations of uncivilized, hostile outsiders—only to overturn them immediately. The Maltese demonstrate extraordinary φιλανθρωπία, forcing readers to reconsider the reliability of cultural and ethnic labels as moral predictors. The narrative exposes ethnic stereotyping as both unstable and ethically insufficient.

2. The Malta Episode Reverses the Shipwreck Topos. Ancient literature typically portrays shipwreck survivors encountering dangerous, inhospitable locals. Luke flips this script: the Maltese respond not with violence but with exemplary hospitality and care, embodying virtues that Greek culture claimed as markers of civilization. This reversal repositions supposed “barbarians” as moral exemplars in the story.

3. The Islanders’ Theological Reasoning Is Serious and Coherent. Rather than mocking the Maltese as superstitious, Luke presents them as thoughtful interpreters of divine justice. Their shift from assuming Paul is a murderer to believing he is under divine favor follows careful observation and logical inference based on ancient concepts of Δίκη or possibly the Punic deity Sydyk. Luke respects their reasoning even as he reframes their conclusions.

4. Hospitality Functions as a Marker of Openness to Divine Visitation. The Maltese display the kind of hospitality that, in Luke-Acts, consistently signals receptivity to God’s purposes. Publius’s formal ξενία, Paul’s healing ministry, and the islanders’ generous provisioning establish a relationship of mutual honor. Even without explicit conversions, the narrative portrays the islanders as responding rightly to divine presence.

5. Malta Embodies Luke’s Larger Ethnographic Strategy. Across Luke-Acts, outsiders—Samaritans, centurions, eunuchs, and now Maltese “barbarians”—repeatedly exceed the moral behavior of insiders. The Malta episode crystallizes Luke’s argument that divine receptivity transcends ethnic and cultural boundaries. In a world structured by exclusionary categories, Luke asserts that humane action, not identity, reveals who truly recognizes God’s visitation.

God's Acts for Israel, Gentiles, and Christians: A Theology of Acts | Dr. Joshua Jipp

The Problem of the Barbarians

When Paul and the survivors of a Mediterranean shipwreck stumbled onto the shores of Malta, Luke describes their hosts with a term that appears nowhere else in his two-volume work: οἱ βάρβαροι (the barbarians, Acts 28:2, 4). This terminological choice is striking. Throughout Luke-Acts, the author consistently employs τὰ ἔθνη (the nations or Gentiles) to describe non-Jewish peoples, making his sudden deployment of “barbarians” for the Maltese islanders a deliberate narrative signal that demands explanation.[1] The term carried substantial cultural weight in the Greco-Roman world, functioning as the primary marker of linguistic and cultural otherness—the word by which Greek speakers distinguished themselves from all who existed outside the boundaries of Hellenic civilization.[2]

The scholarly literature has long recognized this terminological anomaly without fully accounting for its narrative function. Some interpreters have suggested that Luke simply reflects the linguistic reality of Malta, where the inhabitants spoke a neo-Punic dialect rather than Greek or Latin.[3] Others have proposed that the term carries its standard pejorative connotations, characterizing the islanders as culturally inferior or intellectually unsophisticated.[4] Neither explanation, however, adequately addresses the central puzzle of the passage: why would Luke introduce a term laden with negative cultural associations precisely at the moment when he wishes to highlight the extraordinary kindness of the Maltese?

This article argues that Luke deliberately employs the loaded term “barbarians” to activate a constellation of Greco-Roman stereotypes about inhospitable, superstitious, and uncivilized islanders—only to systematically subvert each expectation through the narrative that follows. The Maltese display extraordinary φιλανθρωπία (love for humanity or kindness), demonstrate theologically coherent reasoning about divine justice, and extend exemplary hospitality that culminates in the formal establishment of guest-friendship (ξενία) with Paul. By pairing “barbarian” with “philanthropic”—two terms that ancient readers would have considered mutually exclusive—Luke forces his audience to reconsider the validity of ethnic stereotyping as a means of evaluating human character and worth.[5]

This reading strategy aligns with Luke’s broader narrative patterns throughout his two-volume work. The author repeatedly introduces ethnic and cultural stereotypes only to dismantle them through narrative action: Samaritans become models of neighborly love (Luke 10:25–37), Roman centurions display exemplary faith and piety (Luke 7:1–10; Acts 10:1–48), and an Ethiopian eunuch—doubly marked as “other” by geography and bodily status—becomes the first African convert and a model of responsive discipleship (Acts 8:26–40).[6] The Malta episode represents the culmination of this pattern, positioning “barbarians” as ideal recipients of divine visitation precisely at the moment when Paul’s journey to Rome approaches its conclusion. The islanders’ warm reception anticipates the Gentile responsiveness that Paul will prophesy in his final words: “this salvation of God has been sent to the Gentiles; they will listen” (Acts 28:28).

The following analysis proceeds in five major sections. First, we examine how ancient Greco-Roman discourse constructed the category of “barbarian” and the specific associations this term carried for educated readers. Second, we trace the literary topos of shipwreck narratives and the conventional expectation that sailors who washed ashore on unfamiliar islands would encounter hostile or savage inhabitants. Third, we provide a close reading of Acts 28:1–11, demonstrating how Luke systematically reverses each element of the “hostile barbarian” stereotype. Fourth, we analyze the theological reasoning of the islanders concerning divine justice and its relationship to Punic religious concepts. Finally, we situate this episode within Luke’s broader ethnographic vision, arguing that the Malta narrative provides crucial evidence for understanding how Luke conceptualizes the relationship between ethnic identity and membership in the people of God.

Constructing the Barbarian: Greco-Roman Ethnographic Discourse

Semantic Range of Barbaros

The Greek term βάρβαρος originated as an onomatopoeia, imitating the “bar-bar” sound that Greek speakers perceived when listening to unintelligible foreign languages.[7] In its primary semantic function, the term designated linguistic otherness: a βάρβαρος was simply someone who did not speak Greek. This linguistic criterion established the fundamental binary that organized Greek cultural identity: the world was divided into Hellenes (those who spoke Greek and participated in Greek cultural institutions) and barbarians (everyone else).[8]

The term was not always employed pejoratively. Arnaldo Momigliano and Erich Gruen have demonstrated that many Greek authors expressed genuine admiration for “barbarian wisdom,” recognizing that non-Greek peoples possessed valuable knowledge, sophisticated legal systems, and ancient religious traditions worthy of respect.[9] Herodotus famously presented the constitutional debate among Persian nobles (Histories 3.80–82) as a sophisticated discussion of governmental forms, and his ethnographic descriptions of Persian customs often display curiosity rather than contempt. Xenophon devoted an entire volume, the Cyropaedia, to celebrating the virtues of the Persian ruler Cyrus. Plutarch, despite his Hellenocentric perspective, could acknowledge barbarian contributions to philosophy, astronomy, and statecraft.[10]

Nevertheless, the term carried substantial negative connotations that extended well beyond the simple fact of linguistic difference. As Edith Hall has demonstrated in her foundational study, Greek tragedy played a crucial role in “inventing the barbarian” as a cultural construct that defined Greek identity through contrast with a supposedly inferior other.[11] The Persian Wars crystallized this ideological construction: the Greek victory over Xerxes was interpreted not merely as a military triumph but as the vindication of Greek cultural superiority—freedom over despotism, reason over passion, civilization over chaos.[12] In the aftermath of these conflicts, the term βάρβαρος increasingly carried connotations of cultural inferiority, moral weakness, and political servility.

The connection between speech and reason proved particularly significant. Greek intellectuals perceived an intimate relationship between linguistic capacity, rational thought, and moral virtue. The word λόγος meant both “word” and “reason,” suggesting that those who lacked proper speech also lacked proper rationality.[13] This conceptual linkage meant that barbarians were frequently depicted not merely as speaking differently but as thinking differently—and thinking less well. They were characterized as emotional rather than rational, impulsive rather than deliberate, governed by passion rather than principle. These intellectual deficiencies were thought to manifest in political forms: barbarians lived under despotism because they lacked the rational capacity for self-governance that enabled Greek democracy.[14]

Malta’s Historical and Cultural Context

Malta occupied a distinctive position in the ancient Mediterranean world. Politically, the island had been incorporated into Roman administration since 218 BCE, when it became part of the province of Sicily following the Second Punic War.[15] By the time of Paul’s shipwreck, Malta had been under Roman governance for nearly two and a half centuries. The island’s leading official bears the very Roman-sounding name Publius (Acts 28:7), and the presence of an Alexandrian ship on the island’s opposite shore (28:11) indicates regular commercial integration with Mediterranean trade networks.

Linguistically and culturally, however, Malta retained a distinctly Phoenician character. Archaeological and epigraphic evidence confirms that the island’s population continued to speak a neo-Punic dialect well into the Roman period.[16] The Phoenician colonization of Malta, dating to approximately the eighth century BCE, had established cultural patterns that persisted despite centuries of Greek and Roman influence. Religious inscriptions from the island demonstrate continued devotion to Punic deities, and material culture reflects Phoenician rather than Greco-Roman aesthetic preferences.[17]

Luke’s designation of the Maltese as βάρβαροι was therefore technically accurate from a Greek linguistic perspective: they were Semitic speakers who communicated in neither Greek nor Latin as their primary language.[18] A Greek-speaking traveler arriving on the island would have encountered a significant language barrier, precisely the situation that the term “barbarian” originally described. Yet Luke’s choice to employ this term rather than a more neutral designation like ἐπιχώριοι (natives or locals, as Eusebius later chose when describing the same episode) suggests deliberate rhetorical intent rather than simple ethnographic description.[19]

Shipwreck and Savage Shores: The Literary Topos

The Shipwreck Narrative in Hellenistic Literature

Ancient Mediterranean literature developed a recognizable topos for narrating shipwreck experiences, featuring conventional elements that would have been immediately familiar to educated readers. The pattern typically included an extended storm sequence emphasizing the sailors’ helplessness against divine or natural forces; the breakdown of normal shipboard hierarchy as crisis overwhelmed conventional social structures; moments of despair when all hope appeared lost; and finally, the survivors’ arrival on an unfamiliar shore where their fate remained uncertain.[20] Luke’s storm narrative in Acts 27 follows this conventional pattern with remarkable precision, demonstrating his sophisticated engagement with Hellenistic literary conventions.

The moment of landfall represented the narrative’s crucial turning point. Shipwrecked sailors occupied an acutely vulnerable position: stripped of resources, exhausted from their ordeal, and entirely dependent on the disposition of whoever might inhabit the coast where they had washed ashore.[21] Ancient authors frequently exploited this vulnerability to generate narrative tension, depicting the encounter between shipwrecked strangers and coastal inhabitants as a test that would reveal the moral character of both parties. Would the locals prove hospitable or hostile? Would the strangers receive the protection owed to suppliants, or would they face robbery, enslavement, or death?

The Trope of the Inhospitable Native

A particularly potent version of this narrative pattern associated barbarian coastal populations with violence against shipwrecked strangers. Euripides’ Iphigenia among the Taurians dramatized this trope with enduring influence: the “barbarian” Taurians were depicted as people who routinely sacrificed strangers who washed up on their shores, offering them to the goddess Artemis in a grim inversion of proper hospitality.[22] Herodotus similarly reported that the Tauric “barbarians” (βάρβαροι) sacrificed shipwrecked sailors (Histories 4.103), establishing an ethnographic precedent that reinforced the dramatic portrayal.[23]

The association between barbarian shores and danger to strangers appears throughout ancient literature. In Euripides’ Helen, the “barbarian gates” of Egypt threaten violence to Greeks who approach (line 789). Virgil’s Aeneid depicts Ilioneus questioning whether Carthage is “a country of barbarians” based on the initially hostile reception the shipwrecked Trojans receive (1.538–39).[24] Cicero characterized the refusal of hospitality to strangers as both “inhumane” and “barbaric” (Against Verres 2.4.25), making explicit the conceptual link between civilization and hospitable treatment of the vulnerable.[25]

The Odyssey established the paradigmatic framework for this literary pattern. As Odysseus approached each new island during his wanderings, he repeatedly voiced the same anxious question: “To the land of what mortals have I now come? Are they insolent, wild, and unjust? Or are they hospitable to strangers and fear the gods in their thoughts?” (Odyssey 6.119–21; cf. 9.172–76; 13.200–02).[26] This binary—hospitable god-fearers versus savage transgressors—structured the Odyssean narrative and established expectations that subsequent authors could exploit. The Cyclopes episode (9.252–370) represented the paradigmatic case of inhospitable barbarism: Polyphemus violated every convention of guest-friendship, devouring his “guests” rather than feeding them, and explicitly rejected the divine sanction that protected suppliants.[27]

Hospitality to the Shipwrecked as Supreme Virtue

The inverse of the “hostile barbarian” trope celebrated hospitality to shipwrecked strangers as an expression of supreme moral virtue. Seneca devoted substantial attention in De Beneficiis (On Benefits) to the philosophical significance of benefactions extended to those who could offer no reciprocal advantage.[28] The shipwrecked stranger represented the limit case: arriving destitute, without resources, connections, or ability to repay, such a person could offer nothing in return for any kindness received. Generosity toward the shipwrecked therefore demonstrated pure φιλανθρωπία—love for humanity as such, unmotivated by any calculation of advantage.

Dio Chrysostom developed this theme in his discourse known as “The Hunter” (Oration 7.51–54), presenting the reception of shipwrecked sailors as evidence of genuine moral excellence precisely because no reciprocity could be expected.[29] The philosophical reasoning was straightforward: if one showed kindness only to those who might return the favor, one’s generosity was merely disguised self-interest. Only the benefactor who aided the utterly helpless demonstrated authentic virtue. By this standard, the Maltese islanders’ treatment of Paul and his companions—276 bedraggled, cold, and exhausted survivors of a shipwreck—would represent the highest possible expression of φιλανθρωπία.

Reader Expectations in Acts 27–28

Luke’s storm narrative in Acts 27 builds toward the Malta landing with mounting tension. The chapter details a catastrophic Mediterranean voyage: departure against Paul’s prophetic warning (27:10), the terrifying northeaster (εὐρακύλων, 27:14), the desperate jettisoning of cargo and tackle (27:18–19), the loss of all hope for salvation among the crew (27:20), and finally Paul’s angelic reassurance that all aboard would survive despite the ship’s destruction (27:22–26). When the ship finally runs aground and breaks apart, leaving the survivors to swim or float to shore (27:41–44), Luke has positioned his readers to wonder what reception awaits them.

The opening of chapter 28 initially confirms the reader’s potential anxieties. The island is identified, but Luke immediately designates its inhabitants with that freighted term: οἱ βάρβαροι (28:2). No “brothers” await them, as at Ptolemais (21:7), Tyre (21:3–6), or Puteoli (28:14). No “friends” are mentioned, as with Julius the centurion at Sidon (27:3). Paul arrives as a complete stranger among people marked by the very term that ancient literature associated with hostility toward strangers. The literary setup invites the reader to anticipate an inhospitality episode—the hostile natives who will threaten Paul before he can reach Rome.[30]

Systematic Reversal: Close Reading of Acts 28:1–11

The Jarring Juxtaposition (28:1–2)

Luke’s reversal begins immediately and dramatically. Having introduced the Maltese as οἱ βάρβαροι, he pairs this term with a description that would have struck ancient readers as nearly oxymoronic: “The barbarians showed us unusual kindness” (οἱ βάρβαροι παρεῖχον οὐ τὴν τυχοῦσαν φιλανθρωπίαν ἡμῖν, 28:2a). The phrase οὐ τὴν τυχοῦσαν (not the ordinary or unusual) employs litotes—a rhetorical understatement that emphasizes by negation. The islanders’ kindness was not merely adequate but extraordinary, exceeding normal expectations.[31]

The term φιλανθρωπία (love for humanity) carried considerable weight in Greco-Roman moral discourse. It designated the disposition of benevolence toward human beings as such—the virtue that motivated generous treatment of others regardless of their status, origin, or capacity for reciprocation.[32] Commentators have sometimes translated the term simply as “kindness,” but this rendering understates its philosophical significance. Φιλανθρωπία represented a fundamental orientation toward the human other, a disposition that transcended particular relationships to embrace humanity universally. It was precisely the virtue that barbarians, in Greek stereotyping, were thought to lack.[33]

Luke specifies the concrete expression of this φιλανθρωπία: “having kindled a fire, they welcomed us all because of the rain that had set in and because of the cold” (28:2b). The details are prosaic but significant. The islanders responded to immediate human need—wet, cold, exhausted survivors required warmth and shelter. They did not first inquire about the strangers’ identity, legal status, or capacity for repayment. They did not hesitate or deliberate. They simply recognized human beings in distress and acted to relieve that distress. The verb προσελάβοντο (they welcomed or they received) emphasizes the inclusive nature of their hospitality: they received “all of us” (πάντας ἡμᾶς)—all 276 survivors, including prisoners like Paul.[34]

The narrative thus forces the reader to hold together two terms that cultural convention had rendered mutually exclusive. “Barbarian” and “philanthropic” do not belong together; the former term was precisely the category that excluded people from the latter virtue. Yet Luke insists on the conjunction. The text challenges its readers to recognize that ethnic categories provide insufficient grounds for predicting moral behavior—that “barbarians” can surpass “civilized” peoples in the very virtues that civilization claims as its distinctive mark.[35]

Paul and the Viper (28:3–6)

The viper episode extends and complicates the ethnographic reversal. Paul, despite his status as a prisoner under Roman guard, participates in the communal labor of gathering firewood (28:3). This detail characterizes Paul as humble and cooperative, willing to contribute to the common effort despite his precarious legal position. The narrative does not present him as demanding hospitality as an honored guest but as joining in the work that hospitality required.[36]

When a viper emerges from the bundle of sticks and “fastened onto his hand” (καθῆψεν τῆς χειρὸς αὐτοῦ, 28:3), the islanders interpret this event through their theological framework: “When the barbarians saw the creature hanging from his hand, they said to one another, ‘This man is certainly a murderer. Though he has escaped from the sea, Justice has not allowed him to live’” (28:4). The interpretive logic is coherent within ancient theological assumptions. The islanders assume that cosmic order includes mechanisms of retributive justice: those who commit serious crimes cannot ultimately escape divine punishment. If a man survives a shipwreck only to be immediately attacked by a venomous snake, this sequence of events reveals his moral status—he is a murderer whom Δίκη (Justice, personified) has pursued and finally overtaken.[37]

Modern interpreters have sometimes characterized the islanders’ reasoning as “superstitious,” suggesting that their theological interpretation marks them as intellectually unsophisticated.[38] This reading, however, participates in precisely the ethnic stereotyping that Luke’s narrative works to subvert. The islanders’ logic is not superstitious but theological—it reflects a coherent understanding of divine justice that pervaded ancient Mediterranean cultures, including Greek and Jewish traditions. The assumption that the natural world participates in enforcing moral order appears throughout ancient literature, from Hesiod’s assertion that Zeus punishes the unjust through natural disasters to biblical traditions of divine judgment manifested in plagues, floods, and cosmic disturbances.[39]

The Double Reversal (28:5–6)

Paul’s response is remarkably understated: “But he shook off the creature into the fire and suffered no harm” (ὁ μὲν οὖν ἀποτινάξας τὸ θηρίον εἰς τὸ πῦρ ἔπαθεν οὐδὲν κακόν, 28:5). The narrative emphasizes the islanders’ careful observation: “They were expecting him to swell up or suddenly fall down dead. But after they had waited a long time and saw that nothing unusual happened to him, they changed their minds and began to say that he was a god” (28:6).[40]

The islanders’ shift from “murderer” to “god” (θεός) has troubled commentators, some of whom see it as evidence of barbarian fickleness or theological confusion.[41] Yet the narrative presents their reasoning as empirically grounded and logically consistent. They observe carefully (προσεδόκων, they were expecting); they wait patiently (ἐπὶ πολύ, for a long time); they revise their conclusion when the expected outcome fails to materialize (μεταβαλόμενοι, changing their minds). Their initial interpretation was falsified by events, so they formulated a new interpretation that better fit the evidence.[42]

The reader, of course, knows that Paul is neither a murderer nor a god. He is a servant of the God of Israel, protected by divine providence for the mission he must complete in Rome. But the narrative does not mock the islanders for their theological reasoning. Rather, it presents them as engaged in the same interpretive task that all observers of divine action must undertake: discerning the significance of extraordinary events within an available theological framework. Their conclusion about Paul’s divine status is incorrect, but their method—careful observation followed by theological interpretation—is entirely appropriate.[43]

The parallel with Acts 14:8–18 illuminates Luke’s rhetorical strategy. At Lystra, Paul and Barnabas heal a lame man, and the Lycaonians similarly conclude that “the gods have come down to us in human form” (14:11). In that episode, Paul and Barnabas immediately and vehemently reject the divine identification, tearing their garments and rushing into the crowd to correct the theological error (14:14–18). On Malta, by contrast, Paul makes no recorded response to being called a god. The silence is significant: Luke apparently does not consider the islanders’ conclusion sufficiently dangerous to require immediate correction.[44] Perhaps the narrator trusts his readers to understand that Paul is neither murderer nor deity; perhaps he suggests that the islanders’ recognition of divine power at work in Paul is, in some sense, more accurate than their specific theological formulation. The God whom Paul serves is indeed present and active in Paul’s ministry, even if the Maltese misidentify the precise nature of that divine presence.

Hospitality Extended: Publius and the Healing Ministry (28:7–10)

The narrative expands from the initial beach encounter to a more formal expression of hospitality. Publius, identified as “the leading man of the island” (τῷ πρώτῳ τῆς νήσου, 28:7), extends welcome to Paul and his companions. The title πρῶτος (first or leading) likely reflects an official designation—inscriptional evidence confirms that Roman Malta used this terminology for municipal leadership.[45] Publius thus represents not merely a private individual but the island’s official authority, making his hospitality a public rather than merely personal gesture.

Luke’s language emphasizes the formal and generous character of this hospitality: “he welcomed us and for three days entertained us hospitably” (ἀναδεξάμενος ἡμᾶς τρεῖς ἡμέρας φιλοφρόνως ἐξένισεν, 28:7). The vocabulary is significant. The verb ἀναδέχομαι (to welcome or to receive formally) suggests official acceptance. The adverb φιλοφρόνως (hospitably or in a friendly manner) echoes the φιλανθρωπία of verse 2, connecting Publius’s hospitality with the islanders’ initial kindness and reinforcing the friendship vocabulary that pervades the passage. The verb ξενίζω (to entertain as a guest) explicitly invokes the institution of ξενία—the ritualized guest-friendship that created binding relationships between parties from different social groups.[46]

The ξενία relationship involved reciprocal obligations.

As Gabriel Herman has demonstrated in his definitive study, ritualized friendship was typically established between persons from different social systems who had no prior relationship.[47] The ritual created a fictive kinship bond that entailed ongoing mutual obligations: hosts were expected to provide for their guests’ needs, and guests were expected to reciprocate when circumstances permitted. The exchange of gifts often formalized the relationship, providing tangible symbols of the bond and its continuing validity.

Paul fulfills his guest obligations through healing ministry. The father of Publius lies ill “with fever and dysentery” (πυρετοῖς καὶ δυσεντερίῳ, 28:8)—Luke’s medical terminology is precise. Paul visits the sick man, prays, lays hands on him, and heals him. The sequence echoes Jesus’ healing of Simon Peter’s mother-in-law (Luke 4:38–39), reinforcing the characterization of Paul as continuing Jesus’ ministry.[48] When word of this healing spreads, “the rest of the people on the island who had diseases also came and were cured” (28:9), paralleling the mass healings that followed Jesus’ initial miracles (Luke 4:40–41).

The episode concludes with the islanders’ reciprocal generosity: “They also honored us with many honors, and when we were about to sail, they put on board whatever we needed” (28:10). The language of “honors” (τιμαῖς) and provision for the journey functions as the guest-gift that sealed the ξενία relationship.[49] The islanders have fulfilled every obligation of exemplary hosts, and more: they have demonstrated φιλανθρωπία beyond what custom required, transforming strangers into guest-friends and providing abundantly for their continuing journey.

Silence on Proclamation

A striking feature of the Malta episode is its silence regarding explicit Christian proclamation. Unlike Paul’s typical missionary pattern—entering synagogues, preaching the resurrection, establishing communities of believers—the Malta narrative includes no sermon, no baptisms, no mention of faith or conversion.[50] Paul heals, but he does not (at least in Luke’s telling) preach. The islanders honor him, but they are not described as joining “the Way.”

Interpreters have proposed various explanations for this silence. Some suggest that Luke assumes his readers will infer evangelistic activity from the narrative context—Paul would hardly have remained silent about his mission during three months on the island.[51] Others argue that Luke deliberately leaves the episode open-ended, perhaps inviting future missionary engagement with Malta or suggesting that the healing ministry itself constitutes a form of proclamation.[52] Still others see the silence as theologically significant: Luke may be suggesting that genuine φιλανθρωπία and recognition of divine power create the preconditions for later conversion without requiring immediate verbal confession.[53]

Whatever the explanation, the narrative effect is clear: the Maltese “barbarians” are presented in an entirely positive light despite the absence of explicit conversion. Their φιλανθρωπία, their theological seriousness, their exemplary hospitality—all these qualities mark them as people who have responded appropriately to divine visitation, even if their understanding of that visitation remains incomplete. They belong among the hospitable hosts who populate Luke-Acts: Cornelius, Lydia, the Philippian jailer, and others whose reception of apostolic messengers demonstrates openness to the God whom those messengers serve.[54]

Divine Justice on the Shore: Δίκη, Sydyk, and Theological Reasoning

Goddess Dikē in Greek Thought

The islanders’ invocation of ἡ δίκη (Justice, personified as a goddess, 28:4) reflects widespread ancient Mediterranean beliefs about cosmic moral order. In Greek religious and philosophical tradition, Δίκη was the daughter of Zeus, responsible for maintaining justice among mortals and ensuring that wrongdoers faced appropriate consequences.[55] Hesiod portrayed her seated beside her father’s throne, reporting human injustice and prompting divine retribution (Works and Days 256–62). The tragedians invoked her as the power that ultimately catches up with those who violate fundamental moral norms, even when human justice fails.

The concept of Δίκη assumed that the cosmos was morally ordered—that wrongdoing could not ultimately succeed because the structure of reality itself worked against injustice. Nature participated in this moral order: plagues, famines, shipwrecks, and attacks by wild animals could all be interpreted as expressions of divine judgment against wrongdoers.[56] The islanders’ interpretation of the viper attack thus reflects a deeply rooted theological conviction that transcended particular ethnic or religious traditions: the universe itself punishes crime.

Punic Context: Righteousness

Given Malta’s Phoenician heritage, the islanders may have been invoking not (or not only) the Greek Δίκη but a Semitic deity of justice. Phoenician religion included worship of Sydyk (or Sedeq), a deity whose name derives from the Semitic root for “righteousness” or “justice.”[57] The Hebrew cognate צֶדֶק (“righteousness”) appears throughout the Hebrew Bible as a key term for moral and cosmic order. Luke may be translating the islanders’ Punic theological concept into Greek terminology accessible to his audience—rendering Sydyk as Δίκη for readers who would not recognize the Phoenician deity.[58]

Archaeological evidence from Malta confirms the persistence of Phoenician religious practices well into the Roman period. Inscriptions invoking Punic deities, temple remains reflecting Phoenician architectural conventions, and votive objects following Carthaginian styles all indicate that the island’s population maintained distinctively Semitic religious traditions despite political incorporation into the Roman sphere.[59] The islanders’ theology, then, was not simply borrowed Greek philosophy but likely reflected authentic local religious convictions with deep Phoenician roots.

Narrative Function of the Islanders’ Theology

Luke presents the islanders’ theological reasoning without mockery or condescension. Their initial interpretation—that Paul was a murderer receiving divine punishment—was reasonable given their premises and the available evidence. Their revised interpretation—that he was a god—likewise followed logically from those same premises combined with new evidence (his immunity to the viper’s venom). The narrative respects their theological seriousness even while leaving room for readers to recognize the inadequacy of their categories.[60]

The theological reasoning displayed by the islanders serves several narrative functions. First, it demonstrates that the “barbarians” are not irrational or superstitious in a dismissive sense; they operate within a coherent theological worldview and reason carefully from evidence to conclusions. Second, it provides an external witness to the extraordinary nature of Paul’s experience: even outsiders recognize that something divinely significant is happening. Third, it vindicates Paul in advance of his arrival in Rome: If Δίκη/Sydyk has not punished him despite ample opportunity, he must not be the criminal his accusers claim.[61] The islanders’ theological verdict—“he is under divine favor, not divine judgment”—anticipates the legal verdicts that Roman authorities have repeatedly rendered throughout Acts: Paul has committed no crime deserving death or imprisonment (23:29; 25:25; 26:31–32).

Luke’s Ethnographic Vision: Implications and Conclusions

Subversion of Ethnic Stereotyping as Lukan Strategy

The Malta episode represents one instance of a broader Lukan strategy: the systematic subversion of ethnic and cultural stereotypes through narrative demonstration. Throughout Luke-Acts, characters consistently defy the expectations that their ethnic or social categories would generate.[62] The pattern is too consistent to be accidental; it reflects deliberate authorial strategy aimed at disrupting readers’ reliance on ethnic reasoning as a means of evaluating human character.

The parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37) provides the most explicit example. As John Dominic Crossan observed, the parable forces hearers to conjoin two terms that Jewish conventional wisdom held to be mutually exclusive: “Samaritan” and “neighbor.”[63] The lawyer’s question—“Who is my neighbor?”—assumed that some people were neighbors and others were not, with ethnic and religious identity providing the relevant criteria for distinction. Jesus’ parable refuses this framework: neighborliness is determined not by identity categories but by compassionate action. The Samaritan, precisely as a Samaritan, demonstrates the love of neighbor that the law requires, while the priest and Levite—despite their privileged religious status—fail to do so.

Luke’s portrayal of Roman centurions follows a similar pattern. Ancient Jewish audiences would likely have regarded Roman military officers with suspicion at best and hostility at worst—centurions were agents of imperial domination, enforcers of a foreign power’s control over Jewish territory.[64] Yet Luke consistently presents centurions in a positive light. The centurion of Capernaum displays faith that surpasses anything Jesus has found in Israel (Luke 7:1–10). The centurion at the cross confesses Jesus’ innocence (Luke 23:47). Cornelius is described as “devout and God-fearing,” a man who “gave alms generously to the people and prayed constantly to God” (Acts 10:2). Julius the centurion treats Paul with kindness (φιλανθρώπως, Acts 27:3) and protects him from soldiers who would have killed the prisoners to prevent escape (27:43). The ethnic category “Roman centurion” proves inadequate for predicting moral character; these military officers consistently exceed the expectations their social position would generate.[65]

The Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8:26–40) similarly defies categorical expectations. Marked as “other” by both geography (Ethiopian, from the edge of the known world) and bodily status (eunuch, excluded from the assembly of the Lord according to Deuteronomy 23:1), this figure might seem an unlikely candidate for incorporation into God’s people.[66] Yet Luke presents him as a model disciple: he reads Scripture, welcomes instruction, responds with faith, receives baptism, and goes on his way rejoicing. His apparent disabilities—outsider status, physical condition—prove irrelevant to his capacity for faithful response to the gospel.

“Barbarians” versus the “Civilized”

The Malta episode acquires additional force when read against the broader narrative of Paul’s journey from Jerusalem to Rome. Throughout this section of Acts, Paul encounters opposition and hostility from those who should, by cultural logic, have been most receptive to him: fellow Jews who share his heritage, Roman officials who represent civilization and law, religious leaders who claim to serve the same God.[67] The Jerusalem mob seeks to kill him (21:30–36). The chief priests and council bring false charges (23:1–10). King Agrippa dismisses his testimony with sardonic detachment (26:28). Even after Paul’s arrival in Rome, “the local leaders of the Jews” divide over his message, many refusing to believe (28:24–25).

The Maltese “barbarians,” by contrast, receive Paul with extraordinary kindness. They do not accuse him; they do not plot against him; they do not reject him. Instead, they demonstrate precisely the φιλανθρωπία that civilized peoples ought to display but often fail to exhibit. The narrative irony is pointed: the “barbarians” act more humanely than the “civilized,” the outsiders more graciously than the insiders. Luke’s reversal of expectations serves a theological purpose: it demonstrates that receptivity to divine visitation is not correlated with cultural sophistication, religious privilege, or ethnic identity.[68]

Hospitality and the People of God

Throughout Luke-Acts, hospitality functions as a key marker of appropriate response to divine visitation. Those who welcome Jesus’ messengers demonstrate openness to the God whom those messengers represent; those who reject them exclude themselves from the salvation being offered.[69] Jesus’ instructions to the seventy-two make this explicit: missionaries are to accept hospitality where offered and pronounce judgment where refused (Luke 10:5–12). The pattern continues in Acts: Lydia’s hospitality (16:15), the Philippian jailer’s hospitality (16:34), and the hospitality of the Jerusalem church (21:17) all signal receptivity to the apostolic message.

The Maltese islanders’ hospitality places them within this positive pattern. Their φιλανθρωπία toward the shipwrecked strangers, their recognition of divine power at work in Paul, their formal extension of ξενία through Publius, and their generous provision for the departing travelers all demonstrate the disposition that, in Luke’s narrative logic, characterizes those who will ultimately receive God’s salvation.[70] Even without explicit conversion, the islanders have positioned themselves among those who respond rightly to God’s visitation—in contrast to those religious insiders who reject the messengers God sends.

What the Silence on Conversion Might Suggest

The absence of explicit conversion language in the Malta episode invites reflection on Luke’s understanding of how non-Jews relate to Israel’s God and Israel’s Messiah. The narrative does not require the islanders to abandon their ethnic identity or cultural practices; it does not describe them receiving baptism, adopting Jewish customs, or joining the community of believers. Yet it presents them in an overwhelmingly positive light, as exemplars of the φιλανθρωπία and hospitality that characterize those who embrace God’s purposes.[71]

This portrayal may suggest that Luke envisions a spectrum of appropriate responses to divine visitation. At one end are those who hear the gospel, believe, receive baptism, and join the community of Jesus’ followers. At the other end are those who reject the message and its messengers, excluding themselves from the salvation offered. Between these poles may lie those like the Maltese: people who respond with φιλανθρωπία and openness, who recognize divine power at work, but who have not (yet) received explicit proclamation of the gospel. Their hospitality creates the conditions for eventual conversion without constituting conversion itself.[72]

The Malta episode thus functions as a narrative bridge between Paul’s final rejection by significant elements of the Jewish community (28:24–28) and the open-ended conclusion that emphasizes God’s salvation going forth “to the Gentiles” who “will listen” (28:28). The hospitable barbarians anticipate the Gentile receptivity that Paul prophesies, demonstrating in advance that those whom Jewish tradition classified as outsiders—linguistically, culturally, religiously “other”—are capable of the very φιλανθρωπία and hospitality that signal openness to God.[73]

Maltese Analeptically Embodies Lukan Narrative Topos

Luke’s deployment of the term βάρβαροι for the Maltese islanders represents a sophisticated rhetorical strategy that activates ancient ethnic stereotypes only to subvert them systematically. The narrative pairs “barbarian” with “philanthropic,” forcing readers to recognize that ethnic categories provide inadequate grounds for moral evaluation. The islanders’ hospitality, theological reasoning, and generous provision for the departing travelers all demonstrate virtues that Greek cultural discourse reserved for the “civilized”—virtues that the ostensibly civilized, throughout Paul’s journey, have frequently failed to display.

The Malta episode participates in Luke’s broader narrative project of disrupting ethnic reasoning as a means of determining who belongs to God’s people. Samaritans, centurions, Ethiopian eunuchs, and Maltese barbarians all defy categorical expectations, demonstrating that receptivity to divine visitation transcends ethnic, cultural, and religious boundaries. This narrative strategy does not erase ethnic difference—Luke consistently identifies characters by their ethnicity and does not require Gentiles to become Jews—but it does refuse to treat ethnic identity as predictive of spiritual capacity.[74]

For contemporary readers, Luke’s ethnographic reversal carries continuing significance. In contexts where ethnic and cultural categories continue to shape assumptions about human character and worth—where “barbarian” equivalents structure perception of migrants, refugees, and those marked as culturally “other”—the Malta narrative offers a counter-testimony. The shipwrecked strangers received extraordinary kindness from those whom cultural convention dismissed as uncivilized. The “barbarians” demonstrated the φιλανθρωπία that the “civilized” too often withhold. Luke’s ancient text speaks with uncomfortable directness to modern tendencies toward ethnic stereotyping, challenging readers to recognize that humanity—and the capacity for humane action—transcends the categories by which we habitually sort and dismiss one another.[75]

Endnotes

[1] The term βάρβαροι appears in Acts only at 28:2 and 28:4. For Luke’s typical use of τὰ ἔθνη, see Acts 4:25, 27; 7:7, 45; 9:15; 10:45; 11:1, 18; 13:19, 42, 46–48; 14:2, 5, 16, 27; 15:3, 7, 12, 14, 17, 19, 23; 18:6; 21:11, 19, 21, 25; 22:21; 26:17, 20, 23; 28:28.

[2] Hans Windisch, “βάρβαρος,” TDNT 1:546–53; Edith Hall, Inventing the Barbarian: Greek Self-Definition through Tragedy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), 1–17.

[3] Colin J. Hemer, The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History, WUNT 49 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1989), 152–53.

[4] C. K. Barrett, The Acts of the Apostles, ICC (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1998), 2:1224.

[5] Joshua W. Jipp, “Hospitable Barbarians: Luke’s Ethnic Reasoning in Acts 28:1–10,” JTS 68 (2017): 23–45, at 33.

[6] On Luke’s pattern of subverting ethnic stereotypes, see Laurie Brink, Soldiers in Luke-Acts: Engaging, Contradicting, and Transcending the Stereotypes, WUNT 2.362 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014), 166; Gay L. Bryon, Symbolic Blackness and Ethnic Difference in Early Christian Literature (London: Routledge, 2002), 108–15.

[7] Hall, Inventing the Barbarian, 4–7.

[8] Paul A. Cartledge, The Greeks: A Portrait of Self and Others, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 38–39, 51–77.

[9] Arnaldo Momigliano, Alien Wisdom: The Limits of Hellenization (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975), 1–21; Erich S. Gruen, Rethinking the Other in Antiquity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 1–37.

[10] On Xenophon’s Cyropaedia as appreciation for Persian virtue, see Deborah Levine Gera, Xenophon’s Cyropaedia: Style, Genre, and Literary Technique (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 1–26.

[11] Hall, Inventing the Barbarian, 56–100.

[12] Ibid., 101–59; Margaret C. Miller, Athens and Persia in the Fifth Century BC: A Study in Cultural Receptivity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 1–42.

[13] Hall, Inventing the Barbarian, 117–21, 199–200.

[14] Ibid., 160–200.

[15] A. J. Graham, “The Colonial Expansion of Greece,” in The Cambridge Ancient History, 2nd ed., vol. 3.3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 83–162.

[16] Hemer, Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History, 152–53.

[17] Claudia Sagona, The Archaeology of Punic Malta (Leuven: Peeters, 2002), 1–45.

[18] Henry J. Cadbury, The Book of Acts in History (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1955), 25, 32.

[19] Michael J. Hollerich, Eusebius of Caesarea’s Commentary on Isaiah: Christian Exegesis in the Age of Constantine (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999), 77.

[20] Jens Börstinghaus, Sturmfahrt und Schiffbruch: Zur lukanischen Verwendung eines literarischen Topos in Apostelgeschichte 27,1–28,6, WUNT 2.274 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), 1–45.

[21] Ibid., 46–89.

[22] Hall, Inventing the Barbarian, 106–10.

[23] Herodotus, Histories 4.103; François Hartog, The Mirror of Herodotus: The Representation of the Other in the Writing of History, trans. Janet Lloyd (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 14–60.

[24] Virgil, Aeneid 1.538–39.

[25] Cicero, Against Verres 2.4.25.

[26] Homer, Odyssey 6.119–21; 9.172–76; 13.200–02.

[27] Homer, Odyssey 9.252–370.

[28] Seneca, De Beneficiis 1.5.4; 3.9.3; 3.35.4; 4.11.1–3.

[29] Dio Chrysostom, Oration 7.51–54.

[30] Cadbury, Book of Acts in History, 25.

[31] On litotes in Acts, see Daniel Marguerat, The First Christian Historian: Writing the ‘Acts of the Apostles’, trans. Ken McKinney et al., SNTSMS 121 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 47–52.

[32] BDAG, s.v. φιλανθρωπία.

[33] Jipp, “Hospitable Barbarians,” 32–33.

[34] Ibid., 34.

[35] John Dominic Crossan, In Parables: The Challenge of the Historical Jesus (New York: Harper and Row, 1975), 64.

[36] Joshua W. Jipp, Divine Visitations and Hospitality to Strangers in Luke-Acts: An Interpretation of the Malta Episode in Acts 28:1–10, NovTSup 153 (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 245–48.

[37] Ibid., 248–56.

[38] Barrett, Acts of the Apostles, 2:1224; I. Howard Marshall, The Acts of the Apostles (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1992), 417.

[39] Hesiod, Works and Days 225–47; Klaus Koch, “Is There a Doctrine of Retribution in the Old Testament?” in Theodicy in the Old Testament, ed. James L. Crenshaw (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983), 57–87.

[40] The verbal parallels with Luke 4:38–41 reinforce Paul’s characterization as continuing Jesus’ ministry.

[41] F. F. Bruce, Commentary on the Book of Acts, NICNT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1954), 523.

[42] Richard I. Pervo, Acts: A Commentary, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2009), 674.

[43] Jipp, Divine Visitations, 256–60.

[44] Jacob Jervell, Die Apostelgeschichte, KKKT 17 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1998), 616.

[45] Hemer, Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History, 153.

[46] Gabriel Herman, Ritualised Friendship and the Greek City (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 29–30.

[47] Ibid., 34–40.

[48] Walter Radl, Paulus und Jesus im lukanischen Doppelwerk: Untersuchungen zu Parallelmotiven im Lukasevangelium und in der Apostelgeschichte (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1975), 211–25.

[49] Herman, Ritualised Friendship, 58–69.

[50] Pervo, Acts, 672; David Peterson, The Acts of the Apostles, PNTC (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 701.

[51] Ronald H. van der Bergh, “The Missionary Character of Paul’s Stay on Malta (Acts 28:1–10) according to the Early Church,” Journal of Early Christian History 3 (2013): 83–97, at 90–91.

[52] Jipp, Divine Visitations, 270–87.

[53] Ibid., 280–87.

[54] Andrew Arterbury, Entertaining Angels: Early Christian Hospitality in its Mediterranean Setting, NTM 8 (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2005), 169.

[55] Hesiod, Works and Days 256–62; Theogony 901–03.

[56] Koch, “Is There a Doctrine of Retribution?” 57–87.

[57] Paolo Xella, “Phoenician Religion,” in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, ed. Karel van der Toorn et al., 2nd ed. (Leiden: Brill, 1999), 658–62.

[58] Jipp, Divine Visitations, 252–56.

[59] Sagona, Archaeology of Punic Malta, 76–112.

[60] Jipp, “Hospitable Barbarians,” 42.

[61] Ibid., 42–43.

[62] Eric D. Barreto, Ethnic Negotiations: The Function of Race and Ethnicity in Acts 16, WUNT 2.294 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), 28–29.

[63] Crossan, In Parables, 64.

[64] Brink, Soldiers in Luke-Acts, 1–45.

[65] Ibid., 166.

[66] Bryon, Symbolic Blackness, 108–15; Clarice J. Martin, “A Chamberlain’s Journey and the Challenge of Interpretation for Liberation,” Semeia 47 (1989): 105–35.

[67] Robert Tannehill, The Narrative Unity of Luke-Acts, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986–90), 2:308–45.

[68] Jipp, “Hospitable Barbarians,” 44.

[69] Luke Timothy Johnson, The Literary Function of Possessions in Luke-Acts, SBLDS 39 (Missoula: Scholars Press, 1977), 1–45, 127–76.

[70] Jipp, Divine Visitations, 270–80.

[71] Matthew Thiessen, Contesting Conversion: Genealogy, Circumcision, and Identity in Ancient Judaism and Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 1–35.

[72] Jipp, Divine Visitations, 280–87.

[73] Loveday C. A. Alexander, Acts in its Literary Context: A Classicist Looks at the Acts of the Apostles, LNTS 298 (New York: T&T Clark International, 2005), 214.

[74] Barreto, Ethnic Negotiations, 184.

[75] Willie James Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 291–93.