Narrative Artistry, Social Dynamics, and Rhetorical Strategy in Paul's Sea Voyage in Acts 27

Acts 27 is far more than a travelogue. Luke’s unusually long, first-person account of Paul’s storm-tossed voyage uses precise nautical detail, suspenseful pacing, and dense intertextual echoes to probe divine providence, authentic leadership, and life under Roman imperial power. Drawing on textual criticism, narrative theory, and trauma studies, the article shows how Acts 27 forges “storm-formed” communities that practice shared discernment, embodied solidarity, costly loss for the sake of people, and resilient hope amid unresolved danger and open-ended endings. It invites readers to treat this shipwreck as a theological laboratory, where careful attention to detail, memory, and communal imagination trains the church to navigate storms now. It also speaks to churches living through prolonged crisis, marked by cultural headwinds, fatigue, and fragmentation.

Greg Camp and Patrick Spencer

12/2/202550 min read

NOTE: This article was researched and written with the assistance of AI.

Key Takeaways

1. Acts 27 Is Theological, Not Just Historical

Acts 27 isn’t mere travel narration; its 59 verses are a deliberate theological slowing of the story. Luke uses storm, ship, and sea to ask what it means to trust God when outcomes are uncertain. The voyage becomes a narrative “laboratory” where divine providence is explored in real time, not asserted in abstraction.

2. Crisis Reveals True Leadership

In the storm, Paul’s authority doesn’t rest on titles but on tested character, discernment, and costly presence. The narrative contrasts Roman power, expert opinion, and economic interests with a leader who listens, stays, and speaks hope. Leadership in Acts 27 is defined by staying on deck with endangered people, not steering from a safe distance.

3. Community Is Saved Together or Not at All

Luke’s repeated emphasis on “we” and on “all” being saved exposes the myth of purely individual deliverance. The turning points in the story hinge on whether people stay together, share information, and resist self-protective escape. Survival becomes a communal event, where shared discernment and solidarity matter as much as nautical skill.

4. Loss Is Real, Yet Not the Final Word

Acts 27 refuses to romanticize faith; the ship, cargo, and economic security are genuinely lost. The narrative honors grief and material damage even as it insists that God’s purposes are not exhausted by those losses. The text trains readers to name what breaks in a storm while still watching for unexpected forms of preservation and new beginning.

5. Storms Become Spaces of Formation

The voyage to Rome functions as a formative journey where characters and readers learn to inhabit unresolved danger faithfully. Acts 27 models practices—listening, remembering promises, sharing food, telling the truth about risk—that shape a resilient community under imperial pressure. Storms, in this reading, are not interruptions to Christian life but classrooms in which the church learns how to live its vocation.

How Acts 27 Forms Christian Imagination Through Ancient Echoes | Dr. Amanda Jo Pittman

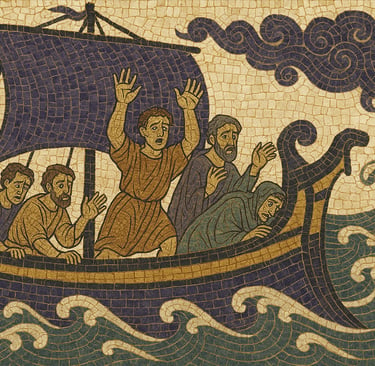

Maritime Adventure

The final chapters of Acts present Paul's dramatic journey to Rome as a prisoner appealing to Caesar. Within this concluding movement, Acts 27 stands out as a literary anomaly that has puzzled interpreters for centuries. Luke devotes 59 verses—roughly 6% of his entire second volume—to describing what amounts to a single sea voyage and shipwreck. This disproportionate attention raises fundamental questions: Why does Luke spend so much narrative energy on travel? What literary, social, and rhetorical purposes does this extended account serve within his broader theological project?

The scholarly consensus recognizes Acts 27 as one of the most detailed maritime narratives surviving from antiquity, containing remarkably accurate nautical terminology, geographical precision, and technical knowledge of Mediterranean sailing conditions.[1] Yet the chapter functions as far more than historical reportage or adventure literature. Through sophisticated narrative techniques, complex social dynamics, and deliberate rhetorical strategies, Luke constructs a multi-layered account that advances his theological vision while engaging readers in profound reflection on divine providence, human leadership, and authentic witness under pressure.

Textual Criticism and the “We-Passages” Problem

The textual foundation of Acts 27 presents intriguing variations across manuscript traditions that significantly impact how interpreters reconstruct the voyage to Rome. The chapter’s first-person plural narration (“we” passages) has been transmitted with notable stability across the major Alexandrian witnesses, even as the Western text occasionally introduces shifts that complicate the narrative voice. In a few places, Codex Bezae (D) and related Western witnesses alter first-person verbs to third-person forms, potentially softening or obscuring the impression of an eyewitness report. The Nestle–Aland 28th edition notes several significant variants in Acts 27:37, where the precise number “276 persons” aboard the ship appears alongside readings such as “275” or “about 76” in certain minuscule manuscripts (614, 1505), suggesting scribal discomfort with the exact headcount and the level of detail it implies.[2]

The “we” narrative technique itself has long sat at the crossroads of historical and literary questions. On one side stand arguments that treat the first-person plural as a marker of personal participation, perhaps preserving travel notes from a companion of Paul. On the other side are readings that view the “we” voice as a crafted literary device, intended to pull the implied audience more deeply into the narrated journey. Colin Hemer’s detailed analysis of Acts 27–28, for instance, stresses the dense network of nautical, geographical, and seasonal details that appear to resonate with the realities of ancient Mediterranean navigation, reinforcing the impression of concrete experience embedded in the narrative. At the same time, the selective use of “we,” confined to particular sections of Acts, pushes readers (listeners) to consider how Luke employs shifts in narrative voice to shape the reader’s perception of key episodes rather than simply reporting travel logs.

Amanda Pittman’s work on scriptural imagination reframes these debates by asking not only whether the “we” indicates eyewitness presence but what the first-person voice does to shape readers’ engagement with the text (see further discussion below).[3]

Recent scholarship has revolutionized understanding of Acts 27 through advances in narrative criticism, social-scientific analysis, and ancient rhetorical theory. International researchers have illuminated the chapter's literary sophistication, its engagement with classical literary traditions, and its significance within Mediterranean cultural contexts.[4] These scholarly perspectives reveal that Acts 27:1-28:10 represents a carefully constructed narrative that operates simultaneously on multiple levels—as historical account, theological statement, and cultural commentary.

Length and Placement Problem

Quantitative Disproportions

The extraordinary length of Acts 27:1-28:10 constitutes the narrative's most immediate puzzle. At 59 verses spanning two chapters, this single voyage account occupies approximately 6% of Acts' total content. To appreciate this disproportion, consider that Luke describes Paul's entire three-year Ephesian ministry—arguably the most productive period of his missionary career—in just 41 verses (Acts 19:1-41). The Jerusalem Council deliberations that determined Gentile Christianity's relationship to Jewish law receive only 35 verses (Acts 15:1-35). Paul's dramatic conversion and commission occupy 22 verses (Acts 9:1-22).

The contrast with other travel narratives in Acts proves equally striking. Paul's journey from Troas to Philippi, marking Christianity's initial entry into Europe, requires merely 7 verses (16:11-17). His return journey from Corinth to Jerusalem, covering similar Mediterranean distances, receives 15 verses (18:18-22). The final journey from Caesarea to Jerusalem, fraught with prophetic warnings and dramatic significance, spans 17 verses (21:15-17). Against these patterns, the 59 verses devoted to the Malta voyage represent a dramatic narrative deceleration demanding explanation.[5]

Luke Timothy Johnson articulated the central interpretive challenge: "Why does [Luke] spend so much time and care on what was after all only a voyage?"[6] This question has generated diverse scholarly responses ranging from source-critical theories about preserved eyewitness documents to literary arguments about classical imitation. Yet the very persistence of this question across scholarly generations suggests that Acts 27's length serves multiple simultaneous purposes that resist reduction to single explanatory factors.

Strategic Narrative Position

The placement of Acts 27 within the broader Acts narrative proves equally significant for understanding its function. The voyage occurs at a crucial structural juncture—after Paul's extended trials and apologetic speeches in Caesarea (Acts 23-26) but before his arrival and ministry in Rome (Acts 28:16-31). This positioning creates a transitional moment where the narrative's geographical movement mirrors theological developments in Paul's mission and status.

The voyage follows immediately after Festus's declaration to Agrippa that Paul "appealed to be kept in custody for the decision of the Emperor" (25:21). This legal framework establishes the journey's official purpose while creating narrative tension about its ultimate outcome. Will Paul reach Rome alive? Will the voyage itself present additional obstacles to fulfilling the divine commission articulated in Acts 23:11, where the Lord tells Paul, "Just as you have testified about me in Jerusalem, so you must also testify in Rome?"

Coming near the end of the Acts' narrative creates what Troy Troftgruben identifies as strategic "suspense" that prepares readers for the book's deliberately open ending.[7] Rather than providing neat narrative closure with Paul's trial verdict, acquittal, or martyrdom, Acts concludes with Paul "proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance" (28:31). The extended voyage narrative, with its accumulating dangers and repeated threats to Paul's survival, trains readers to expect ongoing witness despite continued uncertainty about final outcomes.

This structural placement also positions the sea voyage as the climactic demonstration of themes Luke has developed throughout Acts: divine providence operating through natural events, authentic leadership emerging during crisis, the universal scope of God's salvation encompassing all people regardless of social status, and the unstoppable advance of the gospel message despite human opposition and natural obstacles.

Scholarly Explanations Surveyed

Traditional source-critical scholarship often explained Acts 27's unusual length through theories about Luke's incorporation of pre-existing travel documents or personal diaries. The shift to first-person plural narration in the "we-passages" (27:1-28:16) suggested to many interpreters that Luke drew upon eyewitness accounts—either his own participation or another companion's written records—that preserved detailed observations about the voyage.[8]

Vernon Robbins advanced an influential alternative explanation in the 1970s, arguing that first-person plural narration represented a conventional literary device in ancient sea voyage accounts rather than evidence of eyewitness participation.[9] Robbins identified parallels with other Mediterranean maritime literature where authors employed first-person narration to enhance narrative vividness and reader engagement. However, subsequent scholarship has challenged Robbins' thesis on multiple grounds: not all ancient sea voyages employ first-person narration, the "we-passages" in Acts include extensive land travel alongside maritime journeys, and Acts shares more formal features with historiographical works than with romance literature or novelistic fiction.[10]

Dennis MacDonald proposed that Luke deliberately modeled Acts 27-28 on Homer's Odyssey, specifically Odysseus's shipwrecks in Books 5 and 12.[11] MacDonald identified shared vocabulary, parallel narrative structures, and common plot elements suggesting intentional literary imitation. Some have criticized his MacDonald on the basis that similar maritime experiences naturally produce similar narratives, the proposed parallels often appear forced, and the technical precision of Acts 27 exceeds what purely literary imitation would require.[12]

On a similar note, Richard Pervo argued that Acts should be read as an ancient novel, with Acts 27 exemplifying typical adventure fiction motifs including late-season departure, passengers more knowledgeable than the captain, cargo jettisoning, crew escape attempts, and encounters with indigenous peoples on strange coasts.[13] However, this interpretation struggles to explain the chapter's unusual technical precision, its lack of typical romance novel features, and its integration within the broader historical framework Luke establishes throughout Acts.[14]

These competing explanations share a common limitation: each attempts to explain Acts 27's distinctive features through single-factor analysis. Contemporary scholarship increasingly recognizes that the chapter's length and characteristics result from multiple converging purposes—historical preservation, literary artistry, theological instruction, and rhetorical persuasion—that operate simultaneously within Luke's sophisticated compositional strategy.[15]

Narrative Structure and Pacing

Three-Part Dramatic Structure

Luke constructs Acts 27:1-28:10 as a carefully balanced three-act drama, with each section centered on Paul's speeches and the centurion Julius's evolving responses. This structural pattern reveals Luke's primary concern with authority, leadership, and divine sovereignty rather than mere adventure narrative or travel documentation.[16]

The first act (27:1-12) establishes the journey's parameters and introduces the central conflict between expert opinion and prophetic insight. Luke provides extensive geographical detail as the voyage progresses from Caesarea through Sidon to the southern coast of Asia Minor, then westward along Crete's coast. The narrative pace remains relatively brisk through these early stages, with Luke noting various ports and sailing conditions in summary fashion.

The dramatic tension emerges at Fair Havens on Crete's southern coast, where "much time had been lost, and sailing was now dangerous because even the Fast had already gone by" (27:9). The reference to "the Fast"—the Day of Atonement falling in late September or early October—establishes the chronological framework while signaling danger, since Mediterranean sailing became increasingly hazardous after mid-September and typically ceased entirely by mid-November.[17]

Paul's prophetic warning introduces the act's central conflict: "Men, I perceive that the voyage will be with injury and much loss, not only of the cargo and the ship, but also of our lives" (27:10). This statement establishes Paul's prophetic authority while creating narrative tension about whether his warning will be heeded. The centurion Julius must choose between Paul's spiritual insight and the pilot's professional expertise, deciding "to put out to sea from there, on the chance that somehow they could reach Phoenix and winter there" (27:12).

Julius's decision to trust the ship's captain and owner over Paul's warning represents more than mere plot development—it establishes patterns of authority and decision-making that will be dramatically reversed as the voyage progresses. Luke notes that "the majority" supported the decision to sail, highlighting how democratic consensus can oppose prophetic wisdom when material interests and professional confidence override spiritual discernment.

The second act (27:13-38) chronicles the escalating storm crisis and Paul's emergence as the voyage's true leader despite his prisoner status. A deceptively favorable south wind encourages departure from Fair Havens, but "not long afterward, there rushed down from it a tempestuous wind, called the northeaster" (27:14). Luke's description of the storm's progression demonstrates sophisticated understanding of Mediterranean meteorology: the crew must use undergirding cables to strengthen the hull, strike the mainsail to prevent capsizing, jettison cargo to lighten the ship, and finally abandon all hope of navigation as "neither sun nor stars appeared for many days" (27:20).[18]

The narrative pace slows dramatically during the storm sequence, with Luke recording specific actions, temporal markers, and emotional states that create reader immersion in the crisis. This deceleration from the summary pace of earlier travel sections represents what Gérard Genette identifies as movement toward "scene"—narrative approximating real-time representation of events.[19] The effect draws readers into the experience of sustained maritime danger while building suspense about the voyage's outcome.

Paul's second speech (27:21-26) provides the act's turning point, transforming him from ignored warner to acknowledged prophet whose authority now supersedes all human expertise. The speech begins with mild rebuke—"Men, you should have listened to me and not have set sail from Crete"—establishing Paul's vindication before proceeding to divine revelation. An angel's appearance promising Paul's survival and Roman testimony establishes both the theological framework (God's purposes will not be thwarted) and the practical outcome (all will survive despite ship loss).

The speech's rhetorical structure moves from past judgment through present revelation to future encouragement: "So take heart, men, for I have faith in God that it will be exactly as I have been told. But we must run aground on some island" (27:25-26). This progression from vindication through divine promise to practical prediction demonstrates Paul's integration of spiritual authority with pragmatic leadership.

The meal scene (27:33-38) provides crucial character development while advancing the theological themes. After fourteen days without food, Paul urges the crew and passengers to eat, taking bread, giving thanks publicly, breaking it, and beginning to eat. Luke's description employs terminology evocative of Jesus's Last Supper and post-resurrection meals, though the narrative carefully notes that "all" were encouraged and ate—suggesting a practical meal rather than restricted Eucharistic celebration.[20]

The scene demonstrates Paul's pastoral leadership, practical wisdom, and ability to maintain hope during crisis. His public thanksgiving before "all" (276 people according to verse 37) represents bold religious witness within a pagan environment, claiming divine providence and protection despite circumstances suggesting abandonment. The meal's communal dimension creates temporary unity among the socially diverse ship population, modeling how crisis can generate solidarity across conventional status boundaries.

The third act (27:39-28:10) narrates the shipwreck, survival, and Paul's vindication through ministry on Malta. The crew's attempted escape (27:30-32) creates additional drama while demonstrating Paul's continued prophetic insight and Julius's growing trust. When sailors lower the ship's boat under pretense of laying anchors from the bow, Paul warns Julius that "unless these men stay in the ship, you cannot be saved" (27:31). The soldiers' immediate action cutting away the boat demonstrates Julius's complete reversal from his initial rejection of Paul's counsel—the centurion now trusts Paul's judgment over maritime professionals' deceptions.

The shipwreck itself receives vivid description emphasizing both human action and divine preservation. The crew deliberately runs the ship aground on a beach, but "the bow stuck and remained immovable, and the stern was being broken up by the surf" (27:41). The soldiers' plan to kill prisoners—standard procedure preventing escape and avoiding execution for guards who lost their charges—creates final dramatic tension resolved by Julius's intervention "because he wished to save Paul" (27:43).

The Malta landing transitions from survival narrative to status transformation account. The indigenous population's initial kindness, Paul's snake bite survival, and his subsequent healing ministry create escalating demonstrations of divine favor. The narrative concludes with Paul receiving honors and provisions, effectively reversing his prisoner status through supernatural vindication and practical service to the island's inhabitants.[21]

Gérard Genette's theoretical framework for analyzing narrative speed provides crucial insights into Acts 27's distinctive pacing. Genette identifies four basic narrative speeds: ellipsis (narrative silence about story time), summary (brief narration of extended story time), scene (narrative approximating story duration), and pause (narrative time exceeding story time through description or commentary).[22]

Acts progressively decelerates from Paul's arrest in Jerusalem through his trials and voyage to Rome. The three-year Ephesian ministry receives summary treatment in Acts 19, while the relatively brief Caesarean imprisonment receives three full chapters (24-26) of speeches and legal proceedings. This deceleration continues in Acts 27, where the voyage itself receives treatment approaching scene pace during crucial episodes.

"We-Passages" and Narrative Perspective

The shift to first-person plural narration in Acts 27:1 ("And when it was decided that we should sail for Italy...") marks the final "we-passage" in Acts, extending through 28:16. This stylistic feature has generated extensive scholarly debate about its significance and source.

The first-person plural creates several immediate narrative effects. It enhances the account's vividness and immediacy, creating reader identification with the narrator's experience while implying eyewitness authority for the details recounted. The perspective shifts readers from external observers of Paul's activities to participants sharing his dangers and experiences.

The "we-passages" occur exclusively during travel episodes (16:10-17; 20:5-15; 21:1-18; 27:1-28:16), with first-person narration beginning and ending at specific geographical locations. This pattern suggests either the narrator's actual participation in these journeys or Luke's use of a travel source incorporating first-person perspective. The passages display stylistic unity with surrounding material, lacking the rough edges typically marking unintegrated source insertion, yet containing distinctive features including geographical precision and technical terminology exceeding Luke's usual practice.[23]

Craig Keener argues that the "we-passages" reflect genuine eyewitness participation, noting that these sections display greater narrative detail than other Acts portions while demonstrating geographical and chronological continuity suggesting authentic travel diary material. Keener emphasizes that the passages' technical precision and cultural accuracy support eyewitness origin rather than literary convention.[24]

Alternative explanations view first-person narration as rhetorical strategy rather than source marker. Mikeal Parsons argues that the "we-passages" enhance Luke's persuasive authority, functioning as a crucial "third buttress" alongside oral tradition and written witnesses. The apparent eyewitness testimony strengthens Luke's credibility with readers while serving his rhetorical purposes regardless of actual authorship questions.[25]

Luuk van de Weghe offers an innovative psychological approach, applying trauma and memory research to the "we-passages." Van de Weghe argues that Acts 27's vivid, unpolished details reflect "cerebral scars" of actual shipwreck experience, with the distinctive features matching psychological profiles of traumatic memory rather than literary invention.[26] Studies of modern shipwreck survivors show that traumatic maritime experiences create flash-bulb memories with exceptional detail, lasting accuracy, and vivid immediacy—characteristics matching Acts 27's narrative profile. Van de Weghe's analysis of the 1994 Southern Star disaster survivors reveals spontaneous emphasis on identical themes reflected in Acts 27: drive to survive, modeling behavior by a leader, prayer, and hope for salvation.[27]

The debate's persistence reflects the passage's complex evidence. The first-person narration enhances rhetorical authority while potentially preserving eyewitness perspective; the technical precision suggests authentic maritime knowledge while serving Luke's literary purposes; the geographical accuracy demonstrates historical awareness while advancing theological themes. These multiple dimensions need not exclude each other—Luke may well combine personal experience or source material with sophisticated literary artistry and theological reflection in constructing his account.

For present purposes, the "we-passages" function rhetorically to enhance narrative authority and reader engagement regardless of their precise historical origin. The first-person perspective creates intimacy and immediacy that serve Luke's persuasive purposes while inviting readers to identify with the narrator's experiences and perspectives.

Character Development and Social Dynamics

Paul's Multi-Faceted Leadership

Acts 27 presents Paul exercising diverse leadership roles that transcend his formal prisoner status, demonstrating how authentic authority emerges through competence, character, and divine empowerment rather than merely official position. Luke's portrayal develops Paul's characterization through multiple leadership dimensions operating simultaneously throughout the voyage narrative.

Prophetic Authority: Paul's primary role involves prophetic insight discerning divine purposes and communicating them to the voyage community. His initial warning at Fair Havens (27:9-10) establishes this prophetic dimension before its confirmation through events. The warning's vindication through the subsequent storm provides retroactive validation while preparing readers to trust Paul's later pronouncements.

The angel's appearance to Paul (27:23-24) provides direct divine revelation confirming his Roman destiny while promising collective survival despite ship loss. Paul's public declaration of this revelation—"So take heart, men, for I have faith in God that it will be exactly as I have been told" (27:25)—demonstrates prophetic confidence communicating divine purposes to human audiences. This prophetic function parallels Old Testament figures like Joseph and Daniel who interpreted dreams and provided divine guidance within pagan imperial contexts.[28]

Paul's third prophetic intervention prevents the sailors' escape (27:30-32), warning Julius that "unless these men stay in the ship, you cannot be saved" (27:31). This warning demonstrates continued prophetic insight into both human intentions and divine requirements for fulfilling the promised salvation. The immediate response—soldiers cutting away the boat—shows Paul's prophetic authority now commanding instant obedience without debate or resistance.

Pastoral Care: Alongside prophetic authority, Paul exercises pastoral leadership providing emotional and spiritual support during crisis. After days of storm violence and growing despair, Paul addresses the ship's company: "I urge you to take heart, for there will be no loss of life among you, but only of the ship" (27:22). This pastoral encouragement moves beyond mere information transmission to address the emotional and psychological needs of frightened people facing apparent death.

The meal scene (27:33-38) demonstrates Paul's pastoral wisdom integrating practical care with spiritual witness. Recognizing that the crew and passengers have eaten nothing for fourteen days due to seasickness and despair, Paul urges them to take food "for your preservation" (27:34). His public thanksgiving before breaking bread creates a pastoral moment where religious witness serves practical human needs while maintaining hope despite circumstances.[29]

Paul's pastoral approach combines realistic acknowledgment of danger with confident assurance of divine protection. He neither minimizes the genuine threats facing the ship's company nor allows circumstances to overwhelm faith in God's promises. This balanced pastoral style provides a model for religious leadership during crisis, where authentic care requires both honest recognition of difficulty and steadfast confidence in divine providence.

Practical Wisdom: Paul demonstrates practical knowledge of maritime conditions and survival procedures that commands respect beyond his religious authority. His initial warning about sailing dangers reflects genuine understanding of Mediterranean seasonal patterns, prevailing winds, and navigational challenges. Though not a professional sailor, Paul's extensive travel experience (he mentions three previous shipwrecks in 2 Corinthians 11:25) provides practical wisdom about maritime dangers.

During the storm, Paul provides specific practical advice: urge the crew to eat for strength, prevent the sailors' escape to preserve necessary expertise for landing, and prepare for running aground by lightening the ship. This practical wisdom complements rather than contradicts his prophetic authority, demonstrating that spiritual leadership includes attention to material necessities and practical realities.

The Malta episode extends Paul's practical service through healing ministry. After surviving the snake bite, Paul heals Publius's father and subsequently treats other islanders suffering from diseases (28:8-9). This practical service generates gratitude and honor, with the Maltese providing necessary supplies for continuing the journey to Rome. Paul's combination of spiritual ministry and practical service demonstrates integrated leadership that addresses multiple human needs simultaneously.

Status Negotiation: Throughout the voyage, Paul navigates complex social hierarchies while gradually transforming his effective status from prisoner to acknowledged leader. This status negotiation operates within Mediterranean honor-shame dynamics where public recognition of authority depends on demonstrated competence and divine favor rather than merely formal position.

F. Scott Spencer analyzes Paul's Acts 27-28 experience through Victor Turner's three-stage status transformation model: separation (Paul as prisoner), liminality (crisis voyage as transitional space), and aggregation (recognition and honor on Malta).[30] The sea voyage functions as liminal space where conventional status markers lose salience, allowing new authority structures to emerge based on competence and divine vindication rather than official roles.

Paul's initial status as prisoner places him at the social hierarchy's bottom, subject to Julius's authority and dependent on the centurion's goodwill. Yet through the voyage's progression, Paul's demonstrated prophetic insight, practical wisdom, and divine favor generate informal authority that eventually supersedes the captain's professional expertise and the soldiers' military power. By the shipwreck, Julius acts primarily to protect Paul rather than guard a dangerous criminal, while the soldiers obey Paul's warnings over their own tactical assessments.

The Malta episode completes Paul's status transformation through public vindication. The snake bite survival leads natives to regard him as divine (28:6), while his healing ministry generates honor comparable to elite benefactors. Publius, identified as the island's "leading man" (28:7), hosts Paul and his companions for three days, with Paul reciprocating through healing Publius's father. This patron-client relationship establishment demonstrates Paul's effective status elevation to elite recognition despite his formal prisoner status.[31]

Julius the Centurion's Evolution

The centurion Julius undergoes the narrative's most dramatic character development, evolving from Paul's guard who rejects his counsel to his protector who trusts his judgment implicitly. This evolution provides a structural backbone for the three-act narrative while demonstrating how authentic authority earns recognition through demonstrated competence and character.

Luke introduces Julius as "a centurion of the Augustan Cohort" (27:1), immediately establishing his official status and military authority. The designation "Augustan Cohort" connects Julius to imperial service, suggesting elite military status befitting prisoner transport to Caesar's court. Julius's initial treatment of Paul shows courtesy exceeding mere duty—permitting Paul to visit friends in Sidon for care (27:3)—yet this kindness reflects personal disposition rather than recognition of Paul's authority.

Michael Kochenash offers an illuminating interpretation of Julius's initial courtesy by connecting it to Socratic literary traditions. Kochenash argues that Julius's characterization deliberately evokes Socrates' prison guard in Plato's dialogues, who develops fondness for the philosopher and facilitates friends' visits.[32] This Socratic parallel maintains Paul's characterization as philosophical-religious teacher even during maritime adventure, demonstrating Luke's ability to weave multiple literary influences into coherent narrative.

At Fair Havens, Julius faces his first crucial decision: whether to trust Paul's warning against continued sailing or follow the pilot and ship owner's professional advice. Luke notes that Julius "paid more attention to the pilot and to the owner of the ship than to what Paul said" (27:11). This decision appears entirely reasonable from Julius's perspective—professional maritime experts possess more relevant expertise than a religious teacher for navigation decisions. Yet Luke's narrative framework establishes this reasonable decision as tragic error, with the subsequent storm vindicating Paul's prophetic insight.

The storm crisis transforms Julius's relationship with Paul through accumulated evidence of Paul's supernatural insight and divine favor. Paul's initial warning's vindication provides retrospective validation, while the angel's appearance to Paul establishes divine revelation as the source of his knowledge. Julius must grapple with the reality that conventional expertise and professional confidence have failed catastrophically, while Paul's religiously grounded warnings prove accurate.

The sailors' attempted escape forces Julius to choose between maritime professionals' judgment and Paul's warning. The sailors' deceptive pretense—claiming to lay anchors from the bow while actually preparing to abandon ship—demonstrates that professional expertise can serve self-interest over collective welfare. Paul's warning that "unless these men stay in the ship, you cannot be saved" (27:31) requires Julius to trust spiritual insight over pragmatic self-preservation. The soldiers' immediate action cutting away the boat demonstrates Julius's complete transformation—he now trusts Paul's counsel absolutely, even when it contradicts apparent tactical wisdom.

The climactic demonstration of Julius's changed perspective occurs during the shipwreck when soldiers plan to kill prisoners preventing escape. Standard military procedure required guards to execute prisoners who might flee, with guards facing execution themselves for lost charges. Yet Julius "wishing to save Paul, kept them from carrying out their plan" (27:43). This statement reveals Julius's motivation: not merely following orders or maintaining his charge but actively protecting Paul despite professional risks.[33]

Julius's character development demonstrates how authentic spiritual authority earns recognition even from those initially skeptical or antagonistic. The transformation occurs through accumulated evidence of Paul's prophetic accuracy, practical wisdom, and divine favor, creating a portrait of conversion to Paul's authority if not necessarily to his faith. Luke's portrayal suggests that genuine spiritual authority creates its own validation through demonstrated truthfulness and divine empowerment.

The Ship as Social Microcosm

The ship's 276 passengers (27:37) represent a compressed social world containing diverse statuses, backgrounds, and interests forced into temporary community by maritime circumstances. Luke's presentation of this floating society illuminates ancient Mediterranean social structures while demonstrating how crisis reconfigures conventional hierarchies.

Social Stratification: The voyage company includes multiple status levels reflecting broader Roman social organization. At the top, the ship's owner and pilot represent commercial elite controlling valuable property and technical expertise. The centurion Julius commands military authority over soldiers and prisoners, occupying middle-range status within imperial hierarchy. The sailors possess specialized skills commanding respect within maritime contexts while lacking broader social prestige. Prisoners represent society's margins, stripped of civil rights and subject to constant surveillance.

Luke also mentions "we" (Paul and his companions) and "others" (27:1), suggesting additional passengers including merchants, government officials, or travelers pursuing various purposes. This diverse company creates a microcosm of Roman Mediterranean society, with the voyage forcing cooperation across boundaries that would normally maintain social distance.

Status Fluidity During Crisis: The storm's violence generates status fluidity as conventional hierarchies prove inadequate for maritime emergency. The owner and pilot's professional expertise fails to prevent catastrophe, undermining their authority claims. Julius's military power cannot command the wind or sea, reducing his coercive authority's effectiveness. The sailors' technical skills remain valuable but prove insufficient for salvation without divine intervention.

Paul's status transformation illustrates crisis-driven authority reconfiguration. His formal prisoner status places him at the hierarchy's bottom, yet his prophetic insight and divine favor elevate him to functional leadership. By the storm's conclusion, even military and commercial authorities defer to Paul's judgment, creating what Victor Turner terms "communitas"—temporary social equality emerging during liminal crisis experiences.[34]

Economic Relationships: The voyage's economic dimensions reveal complex relationships between commerce, security, and survival. The ship carries "a cargo of grain from Alexandria" (27:38)—part of Rome's crucial grain supply drawn from Egyptian agricultural surplus. This economic function explains the ship's size (capable of carrying 276 people plus substantial cargo) and the commercial pressures encouraging risky late-season sailing.

The cargo jettisoning (27:18) and tackle disposal (27:19) represent massive economic losses undertaken for survival. These actions demonstrate crisis priorities where preservation of life supersedes property protection, yet the losses affect different social groups unequally. The ship owner bears direct financial catastrophe, while crew members lose employment, and passengers lose transported goods. Paul and fellow prisoners, owning nothing, lose nothing material through the shipwreck.

Luke's description employs terminology evocative of Jesus's Last Supper ("took bread, gave thanks, broke it, and began to eat"), though the narrative carefully indicates universal participation suggesting practical meal rather than restricted Eucharistic ritual.[35] This ambiguity allows multiple interpretive levels: the meal functions practically as necessary nutrition, socially as community formation, and symbolically as divine provision and care.

The meal's aftermath shows renewed collective action: "they all were encouraged and ate. And when they had eaten enough, they lightened the ship, throwing out the wheat into the sea" (27:37-38). The communal eating generates courage for continued survival efforts, while the wheat disposal demonstrates collective commitment to preservation over profit. The ship's diverse company achieves temporary unity through shared danger and Paul's pastoral leadership.

Diverse Responses to Paul: The voyage company's varied responses to Paul illuminate different possible relationships to spiritual authority. Julius evolves from skeptical courtesy through crisis-driven trust to active protection. The soldiers obey Julius's orders protecting Paul while apparently harboring no independent recognition of his significance. The sailors demonstrate pragmatic self-interest, attempting escape despite Paul's warnings. The ship owner and pilot resist Paul's initial counsel, preferring professional judgment over prophetic insight.

These diverse responses suggest that spiritual authority generates varied recognition depending on individuals' openness to supernatural claims, their investment in alternative authority structures, and their willingness to revise judgments based on accumulating evidence. Luke presents Paul's authority as objectively validated through prophetic accuracy and divine favor, yet this validation does not produce universal acknowledgment—different social actors maintain varied relationships to spiritual truth depending on their interests and dispositions.

Suspense as Literary Strategy

Ancient Rhetorical Theory of Suspense

Ancient rhetoricians recognized suspense as a deliberate compositional technique for engaging audiences and enhancing narrative impact. Greek and Latin sources identify multiple components necessary for effective suspense creation, providing theoretical frameworks that illuminate Acts 27's literary strategies.

Aristotle's Poetics discusses how superior poets generate "fear and pity" through carefully constructed narratives where outcomes remain uncertain until final resolution.[36] This emotional engagement depends on audiences caring about characters and being genuinely uncertain about their fates, requiring authors to construct scenarios where multiple outcomes appear possible. Aristotle emphasizes that effective suspense requires more than mere surprise—it demands sustained tension where audiences remain invested in uncertain outcomes.

Quintilian's Institutio Oratoria addresses how speakers and writers create anticipation through careful information management. He notes that effective persuasion often requires withholding certain information while providing enough detail to generate interest and investment. This strategic disclosure creates audiences actively seeking resolution, thereby increasing attention and emotional engagement with the material.

Aelius Theon's Progymnasmata discusses narrative (διήγησις) as fundamental rhetorical exercise, emphasizing how effective narration creates "clarity" (σαφήνεια), "brevity" (συντομία), and "persuasiveness" (πιθανότης). Yet Theon notes that brevity must be strategic rather than absolute—crucial moments deserve extended treatment creating the vividness necessary for persuasive impact. This principle of variable pacing suggests that narrative deceleration during key episodes enhances rather than diminishes overall effectiveness.

Ancient rhetoricians recognized suspense as a deliberate compositional technique for engaging audiences. Troy Troftgruben identifies four key components: anticipation (building expectation), deferring (suspending resolution), uncertainty (raising doubts about outcomes), and empathy (creating reader identification with characters).

Anticipation: Luke establishes expectation for Paul's Roman testimony long before the voyage begins. In Acts 19:21, Paul "resolved in the Spirit to pass through Macedonia and Achaia and go to Jerusalem, saying, 'After I have been there, I must also see Rome.'" This divine necessity language (δεῖ—"it is necessary") indicates that Rome represents more than personal preference or strategic planning—it constitutes divinely ordained destination requiring fulfillment.

The Lord's direct communication to Paul following his Jerusalem arrest reinforces this expectation: "Take courage, for as you have testified to the facts about me in Jerusalem, so you must testify also in Rome" (23:11). This explicit divine promise establishes Rome as certain destination while leaving the means uncertain. The narrative tension emerges from the gap between promised outcome and unknown process—readers know Paul must reach Rome yet remain uncertain how this will occur given accumulating obstacles.[37]

The appeal to Caesar (25:11-12) provides the legal mechanism for Paul's Roman journey while introducing new uncertainties. Will imperial judgment favor or condemn Paul? What dangers await during the voyage? The legal framework transforms Paul's journey from missionary travel to prisoner transport, adding layers of constraint and danger to the anticipated Roman testimony.

Deferring: Acts 27's extraordinary length functions primarily as narrative deferring—suspension of resolution through extended treatment of what could have been summarized briefly. Luke could have written: "Paul sailed under guard to Rome, experiencing shipwreck near Malta before safely reaching the imperial capital." Such summary would preserve essential information while maintaining narrative momentum toward Acts' conclusion.

Instead, Luke devotes 59 verses to the journey, creating what Troftgruben identifies as Acts' "slowest" travel narrative.[38] This dramatic deceleration occurs precisely when readers most anticipate resolution—Paul approaches his divinely promised Roman destination, yet the narrative slows rather than accelerates toward this goal. The deferring technique heightens anticipation through delayed gratification while creating space for theological reflection on the journey's significance.

The fourteen-day storm duration (27:27, 33) extends the crisis temporally, creating what ancient audiences would recognize as sustained peril beyond normal storm experiences. This extended danger multiplies opportunities for catastrophe while testing both Paul's prophetic credibility and divine promises' reliability. Each day without resolution increases tension while demonstrating the severity of circumstances threatening fulfillment of God's purposes.

Uncertainty: Luke introduces multiple threats creating genuine doubt about Paul's survival despite divine promises. The initial sailing decision against Paul's warning establishes that human choices can create circumstances threatening divine purposes. The northeaster's violence exceeds normal storm patterns, with Luke noting that "neither sun nor stars appeared for many days, and no small tempest lay on us" until "all hope of our being saved was at last abandoned" (27:20). This explicit statement of despair signals that circumstances have reached extremity where survival appears impossible.[39]

The soldiers' decision to kill prisoners (27:42) introduces human malice as additional threat beyond natural dangers. Roman military procedure requiring guards to execute potentially escaping prisoners creates systematic threat independent of storm conditions. This human danger demonstrates that even if Paul survives the shipwreck, military logic threatens his life immediately afterward.

The snake bite on Malta (28:3) provides final dramatic threat after survival seems assured. The indigenous population's immediate reaction—"No doubt this man is a murderer. Though he has escaped from the sea, Justice has not allowed him to live" (28:4)—articulates widespread ancient belief that cosmic justice pursues guilty individuals even across natural disasters. The snake incident raises final question: Has Paul survived sea voyage only to die from venom on land?

These accumulating threats create what Troftgruben terms "raising doubts"—genuine narrative uncertainty about whether divine promises will be fulfilled despite apparently insurmountable obstacles. Luke constructs scenarios where survival appears increasingly implausible, thereby magnifying the ultimate resolution's significance while testing readers' confidence in divine providence.[40]

Empathy: The first-person narration creates reader identification with the narrator's experiences, generating emotional investment in the voyage's outcome. The "we" perspective invites readers to share the narrator's dangers, fears, and hopes, transforming them from external observers into virtual participants experiencing events alongside Paul and his companions.

Luke's vivid descriptions of storm violence, accumulated despair, and survival efforts enhance empathetic engagement through sensory details and emotional indicators. The crew's progressive actions—undergirding the hull, lowering the gear, jettisoning cargo, throwing tackle overboard, abandoning navigation—create escalating desperation palpable to readers. The explicit statement that "all hope of our being saved was at last abandoned" (27:20) articulates the emotional nadir shared by all aboard, inviting readers to experience similar despair.

Paul's speeches provide emotional anchors within the crisis, offering hope and encouragement that readers can share alongside the ship's company. His confident assertion that "there will be no loss of life among you, but only of the ship" (27:22) creates emotional relief available to readers alongside fictional characters. The meal scene's communal dimension—where "all" ate and "were encouraged" (27:36-37)—invites readers to participate imaginatively in this restoration of hope and strength.[41]

The cumulative effect of these suspense techniques creates what Troftgruben identifies as distinctive "reading experience" that engages audiences emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually. The extended voyage narrative transforms readers from passive information recipients into active participants wrestling with questions about divine providence, human agency, and authentic leadership under pressure.

The suspense created through Acts 27's literary strategies serves multiple theological purposes beyond mere entertainment or reader engagement. The extended crisis narrative provides experiential framework for understanding how divine purposes operate through rather than apart from natural processes and human choices.

This modeling serves Luke's broader theological project of preparing communities for ongoing witness amid uncertainty and opposition. Acts' open ending—Paul in Rome teaching "with all boldness and without hindrance" (28:31) but without resolution of his legal case—requires readers to maintain confidence that God's purposes advance even without neat narrative closure. The voyage's extended suspense trains readers for this open-ended confidence, demonstrating that divine faithfulness operates independently of immediate visible vindication.[42]

This theological claim challenges conventional assumptions about sacred geography limiting divine presence to temples, synagogues, or established Christian gathering places. The ship becomes sacred space where Paul exercises prophetic authority, provides pastoral care, demonstrates divine power, and creates temporary community across social boundaries. The Malta episode extends this theme, showing Paul's healing ministry operating effectively in remote locations among people who have never encountered Christianity.[43]

The journey's sacralization transforms travel from mere logistics into theological statement about the universal scope of God's kingdom and the unbounded nature of apostolic witness. Paul's prisoner status during this sacred journey demonstrates that divine purposes advance through rather than despite human constraints, with apparent obstacles becoming opportunities for displaying God's power and purposes.

Intertextual Dimensions

Jonah Typology

The Jonah narrative provides crucial intertextual framework for interpreting Acts 27, with multiple parallels suggesting deliberate literary connection between these sea voyage accounts. Both stories feature reluctant westward voyages, storms endangering pagan sailors, divine messages about survival, and ultimate deliverance to unexpected destinations. Yet the parallels function not merely as literary echoes but as theological commentary, with Paul appearing as obedient prophet contrasting with Jonah's initial disobedience.[44]

The prophetic figures' roles differ significantly, revealing Luke's theological purposes through contrast. Jonah initially sleeps during the storm, remaining passive until sailors force his involvement (Jonah 1:5-6). Paul actively leads throughout the crisis, providing warnings, encouragement, practical wisdom, and spiritual guidance. Jonah acknowledges responsibility for the storm and volunteers for sacrifice to save the pagan crew (Jonah 1:12). Paul receives divine assurance that all will be saved through God's protective purposes rather than through his sacrifice.

The post-storm outcomes reveal crucial theological differences. Jonah's deliverance leads to reluctant prophetic mission among Ninevites, with Jonah ultimately angry about their repentance and God's mercy (Jonah 4:1-3). Paul's Malta ministry demonstrates enthusiastic service among indigenous peoples, with healing miracles generating gratitude and honor (Acts 28:7-10). The contrast suggests that Paul embodies true prophetic calling—willing service to all peoples rather than grudging obedience and ethnic exclusivism.

The universal salvation themes operate differently in each account. Jonah's mission brings repentance to Nineveh's population while alienating the prophet from God's merciful purposes. Paul's shipwreck saves all 276 passengers regardless of their religious status or moral condition, demonstrating God's comprehensive care for humanity. Luke presents salvation as including both physical preservation and spiritual transformation, with Paul mediating both dimensions through prophetic authority and practical service.[45]

Gospel Parallels

Vadim Wittkowsky identifies systematic parallels between Acts 27–28 and Luke’s passion narrative, suggesting Luke structured Paul’s sea voyage as theological parallel to Jesus’s death and resurrection. Key parallels include angelic announcements of salvation, bread-breaking scenes that restore hope, triple death threats, and vindication language. These connections suggest Luke understands apostolic ministry as recapitulating Jesus’s death-resurrection pattern.[46]

Vindication Language: The phrase "this man" (ὁ ἄνθρωπος οὗτος) appears in both Paul's vindication (Acts 28:4, 6) and the centurion's testimony about Jesus (Luke 23:47). In both contexts, the expression marks dramatic reversal where apparent criminals receive recognition as righteous. The Maltese population's shift from viewing Paul as murderer deserving cosmic punishment to regarding him as divine parallels the centurion's recognition of Jesus's innocence and righteousness.[47]

Wood Imagery: Wittkowsky proposes that Jesus's cryptic saying about "green wood" and "dry wood" (Luke 23:31) finds fulfillment in Acts 27-28. Paul survives using wet planks (σανίδες) from the shipwreck (27:44) and then gathers dry brushwood (φρύγανα) for fire (28:3), creating formal parallel between wet/dry wood that fulfills Jesus's prophetic words. This connection, while speculative, demonstrates Luke's potential for intricate cross-referencing between his two volumes.[48]

These parallels suggest Luke understands apostolic ministry as recapitulating Jesus's death-resurrection pattern. Paul's near-death experiences and repeated deliverances demonstrate that resurrection power continues operating through apostolic witness, with disciples sharing Jesus's suffering while also experiencing his vindication and life-giving presence.

Homeric Echoes

Dennis MacDonald's proposal that Luke deliberately modeled Acts 27-28 on Homer's Odyssey has generated significant scholarly debate.[49] MacDonald identifies extensive parallels between Paul's shipwreck and Odysseus's maritime disasters in Odyssey Books 5 and 12, arguing for intentional literary imitation rather than coincidental similarity.

Nautical Vocabulary: The most compelling linguistic evidence involves the phrase ἐπέκειλαν τὴν ναῦν ("they ran the ship aground") in Acts 27:41. Kenneth Cukrowski demonstrates that this represents dramatic departure from Luke's normal vocabulary patterns.[50] Luke consistently uses πλοῖον for "ship" (12 times before verse 41, 4 times after), making ναῦς a hapax legomenon in all of Luke-Acts and the entire New Testament. The verb ἐπικέλλω is equally unique and "altogether poetical" rather than standard prose. Both terms paired together frequently appear in Homer's Odyssey, creating distinctive linguistic signature suggesting deliberate classical allusion.

Critical Responses: The Homeric imitation theory faces significant challenges. Critics note that similar maritime experiences naturally produce similar narratives without requiring literary dependence. The proposed parallels sometimes appear forced, requiring interpretive flexibility that weakens the case for intentional mimesis. The technical precision of Acts 27 exceeds what purely literary imitation would require—Luke demonstrates genuine nautical knowledge rather than merely copying Homeric descriptions.[51]

Cukrowski offers more modest claims, arguing that Luke employs brief Homeric allusion in Acts 27:41 to associate Paul with Odysseus's heroic endurance rather than constructing elaborate Homeric imitation throughout the entire narrative.[52] This measured approach recognizes classical echoes without reducing Acts 27 to derivative fiction, allowing for Luke's engagement with multiple literary traditions while maintaining the narrative's historical plausibility and theological purposes.

Julius as Philosophical Prisoner's Guard: The centurion's behavior specifically recalls Plato's depiction of Socrates' jailer who develops fondness for his philosophical prisoner and allows friends to visit providing care. Julius "dealt with Paul humanely (φιλανθρώπως) and allowed him to go to his friends to obtain care (ἐπιμελείας τυχεῖν)" (Acts 27:3). This directly parallels Crito's explanation that Socrates' guard "is used to me by now... owing to my frequent visits" and allows regular access for friends to provide care.[53]

The Socratic reading demonstrates Luke's sophisticated literary technique, weaving multiple classical traditions into Christian narrative that both honors and transcends its cultural sources. Paul emerges as figure embodying Socratic philosophical virtues while surpassing them through Christian conviction and divine empowerment.

Scriptural Imagination in Acts 27: Why Luke Lingers on the Storm

Acts 27 is one of those chapters readers tend to skim until they are in a storm of their own. Then, suddenly, every gust of wind and every discarded piece of cargo feels strangely familiar. Pittman’s work on scriptural imagination helps explain why Luke lingers so long on this voyage to Rome and why this narrative refuses to be trimmed down to a neat summary.[54]

On a purely informational level, the journey could have been reported in a single sentence: “We sailed, encountered difficulty, were shipwrecked, and eventually reached our destination.” Instead, the narrator slows the pace to almost real time, counting off days in which “neither sun nor stars appeared,” cataloguing abandoned plans, and tracing the gradual erosion of hope. The sheer length of the story functions as a kind of interpretive signal. Luke does not want the community merely to know that Paul survived a storm; he wants them to spend time inside the storm.

Pittman’s emphasis on scriptural imagination draws attention to what this extended narration does to its hearers. Rather than offering a detachable moral at the end, Acts 27 works on the imagination by accumulation: detail after detail, delay after delay. The audience is invited to picture the ship creaking under strain, to feel the uncertainty of sailors working by instinct rather than by stars, and to inhabit that haunting line that “all hope of our being saved was at last abandoned.” Scriptural imagination, in this sense, is not about escaping into a distant past but about learning to recognize the patterns of one’s own life within the narrative textures of the text.

The “we” perspective intensifies this effect. It is one thing to hear that “they” despaired of life; it is another to be told “we abandoned hope.” The shift into first-person narration collapses the distance between ancient travelers and contemporary readers. Pittman’s work invites us to see that this is not simply a claim about eyewitness testimony but a literary technique that encourages communities to say “we” with the text. The goal is not detached admiration for Paul’s resilience but a shared imaginative rehearsal of what it looks like to endure when visibility is low and outcomes are uncertain.

The length of Acts 27 also shapes how readers imagine time in crisis. Modern accounts of danger often rush toward resolution: a problem is introduced, tension rises, and within a short span the situation is resolved. Acts 27 resists that compression. Days are counted, conditions worsen, and the narrative allows space for fear and confusion to accumulate before any word of reassurance breaks in. Pittman’s lens helps communities treat this pacing as formative: the chapter trains readers to stop interpreting prolonged crisis as a failure of faith and instead receive it as a realistic account of how trust, courage, and discernment are often formed—slowly, with no guarantee of quick clarity.

Seen in this way, Luke’s decision to devote so many verses to a storm is not a digression from the theological work of Acts. It is one of the chief ways the book does its work. Acts 27 becomes a site where scriptural imagination is patiently formed: readers learn to recognize the fragility of human plans, the limitations of expertise, and the possibilities that emerge when a community continues to act, speak, and care for one another even when no one can yet see the shoreline.

Imperial Negotiation Strategies

Roman Power Structures Present

Acts 27 presents multiple dimensions of Roman imperial authority operating simultaneously, creating complex environment requiring sophisticated negotiation strategies. Warren Carter identifies four distinct structures of Roman power shaping the voyage narrative.[55]

Judicial Authority: Paul's status as prisoner appealing to Caesar demonstrates Rome's legal reach throughout the empire. The appeal mechanism (provocatio ad Caesarem) represents Roman judicial innovation allowing citizens to transfer cases to imperial jurisdiction, theoretically protecting individuals from local prejudice while ensuring imperial oversight of significant matters. Yet this system also concentrates power in imperial hands while subordinating local authorities to central control.

Paul's legal status creates ambiguity—he remains prisoner subject to military custody yet possesses rights through citizenship and appeal. This liminal legal position shapes his entire voyage experience, constraining his freedom while providing protections unavailable to common prisoners. The legal framework simultaneously benefits Paul (enabling Roman journey, preventing immediate execution) and threatens him (subjecting him to imperial judgment with potentially capital consequences).[56]

Military Power: The centurion Julius represents Rome's military might, with his "Augustan Cohort" designation connecting him directly to imperial service. Julius commands soldiers whose authority includes life-and-death decisions over prisoners (27:42), demonstrating coercive power underlying Roman order. The soldiers' plan to kill prisoners reflects standard military procedure prioritizing security over individual lives, revealing systematic violence embedded within Roman structures.

Yet Julius also exercises discretion moderating military violence, showing kindness to Paul and ultimately protecting him from execution. This individual agency within military structures demonstrates that Roman power operates through human choices rather than merely through institutional mechanisms. Julius embodies both threat and protection, coercion and kindness—the ambivalent character of imperial military authority.[57]

Maritime Control: The voyage itself operates within Rome's claimed mastery over Mediterranean waters. Ancient imperial ideology promoted rulers as controllers of seas and lands, with Augustus particularly emphasizing naval power following his victory at Actium. The Alexandrian grain ship transporting Paul represents Rome's maritime commercial network extracting resources from provinces for imperial consumption.

Yet the storm's violence exposes limits to Roman maritime control. Neither imperial ideology nor military authority can command the wind or sea, revealing natural forces beyond Roman mastery. The ship's destruction while passengers survive demonstrates that divine providence operates through and sometimes against Roman structures, asserting transcendent sovereignty relativizing imperial claims.[58]

Economic Domination: The grain cargo represents Rome's tributary economy extracting agricultural surplus from Egypt through taxation-in-kind. Historical sources indicate that Rome claimed 10% of crops from private Egyptian land and 30% to 40% from public land, creating massive wealth transfer funding Roman consumption and political stability. The ship's capacity to transport both 276 passengers and substantial grain cargo demonstrates the scale of this economic system.

The cargo's jettisoning (27:18, 38) represents economic loss serving survival, yet the loss affects different social groups unequally. The ship owner faces financial catastrophe, crew members lose employment, and the imperial grain supply suffers disruption. This economic dimension reveals how Roman prosperity depends on systematic extraction from provinces, with maritime commerce functioning as mechanism of imperial enrichment.[59]

Acts 27 demonstrates sophisticated engagement with Roman power through multiple simultaneous strategies rather than monolithic accommodation or resistance, reflecting early Christian communities’ actual navigation of imperial realities.

Contestation: The narrative asserts God's superior authority through Paul's prophetic insight superseding professional expertise, divine promises fulfilled despite Roman military procedures, and comprehensive salvation demonstrating God's power over nature and empire. This contestation operates through demonstration rather than confrontation, with events revealing divine sovereignty without requiring explicit anti-imperial rhetoric.[60]

Contested Sovereignty

The sea becomes theological battleground where divine and imperial powers interact in complex ways. Rome claims maritime sovereignty through military control and commercial dominance, yet the storm reveals natural forces beyond imperial mastery. God works through Roman structures (Julius's protection, the ship's provisions) while also demonstrating transcendent authority (storm survival, comprehensive salvation, miraculous healings).

The reference to "the Fast" (Day of Atonement, 27:9) subtly evokes Israel's exodus tradition where God's power overwhelmed Egyptian imperial forces in the sea. This intertextual allusion creates theological tension with Roman maritime sovereignty claims, suggesting that the God who defeated Pharaoh's army operates now in Paul's circumstances.[61] The allusion remains subtle rather than polemical, allowing Luke to assert divine sovereignty without directly attacking imperial ideology.

Instead, Carter proposes "aquatic display" model where Acts 27 provides Christ-believers with spectacle demonstrating how to navigate the "stormy imperial world."[62] The chapter presents multiple strategies operating simultaneously—submission, awareness, courage, interaction, contribution, discernment, and contestation—creating sophisticated framework for faithful living within imperial realities.

Acts 27, Empire, and Counter-Narratives of Security

Pittman’s emphasis on counter-cultural imagination also sharpens how Acts 27 engages questions of empire and security. The voyage to Rome unfolds within the infrastructure of the Roman economy: a grain ship carrying precious cargo for the capital, soldiers escorting prisoners, a centurion with authority, professional sailors whose expertise keeps the system moving. On the surface, this looks like a routine expression of imperial stability.

The storm exposes how fragile that stability actually is. Navigation schedules, seasonal calculations, and professional judgments all prove inadequate when conditions deteriorate. The grain ship bound for Rome—an icon of the empire’s ability to provision its center—breaks apart just offshore from an island whose name the travelers do not even know at first. Pittman’s lens encourages readers to see this not as a simple misfortune but as a narrative counterexample to imperial claims of control. Systems designed to guarantee safety and supply are shown to be limited, vulnerable, and at times self-endangering.

Within this setting, Paul’s presence introduces a quiet but persistent alternative. He does not seize formal authority, renounce the ship, or romanticize suffering. Instead, he keeps interpreting events in light of a different horizon of meaning: warning of danger when others are optimistic, naming the reality of loss while insisting that lives can be preserved, urging embodied practices—eating, staying together—that make survival possible. His confidence is not in the ship, the season, or the chain of command. It is in a promise that cuts across those structures without simply discarding them.

Pittman’s focus on scriptural imagination helps contemporary readers see how Acts 27 invites communities to question their own narratives of security. Modern equivalents of the Alexandrian grain ship—financial systems, organizational brands, institutional reputations, carefully managed careers—also promise stability. The chapter does not tell communities to abandon such structures out of hand. But it does imagine a situation in which those structures crack and where survival depends on practices that do not fit neatly within the empire’s scripts: listening to marginal voices, risking costly losses to preserve people, and staying with vulnerable others when escape routes appear.

In that sense, Acts 27 functions as a counter-narrative to both imperial triumphalism and religious triumphalism. It neither guarantees that faithful communities will be spared storms nor suggests that storms signal abandonment. Instead, it trains readers to expect that storms will reveal what their trust has actually been in, and to cultivate patterns of life that do not collapse when familiar supports fail.

Theological Themes and Contemporary Implications

Divine Providence and Human Agency

Acts 27 presents sophisticated understanding of how divine providence operates through rather than apart from natural processes and human agency. The theological framework rejects both deistic assumptions about divine non-involvement and magical thinking expecting constant miraculous intervention, instead demonstrating providence working through ordinary circumstances, human wisdom, and natural events.[63]

The angel's promise that all will survive (27:23-24) establishes divine commitment to comprehensive salvation while leaving implementation mechanisms unspecified. The fulfillment requires no storm calming miracle or supernatural transport to safety. Instead, salvation occurs through accumulated human choices and natural processes: the sailors' expertise detecting land proximity, the decision to run aground on a beach, Julius's intervention preventing prisoner execution, passengers' swimming or floating on debris to shore, and Maltese inhabitants' compassionate hospitality.

This incarnational providence demonstrates that divine purposes saturate ordinary reality rather than interrupting it occasionally through spectacular miracles. God works through Paul's prophetic warnings influencing Julius's decisions, through sailors' technical knowledge enabling safe landing, through favorable circumstances like the beach's location and the Maltese population's kindness. Providence operates comprehensively through creation's normal functioning rather than superseding it.[64]

The theological implications prove significant for communities facing ongoing challenges without expecting constant miraculous deliverance. Acts 27 suggests that God's faithfulness manifests through ordinary human wisdom, accumulated expertise, fortunate timing, and compassionate responses by strangers—not only through spectacular supernatural intervention. This theology encourages believers to exercise agency, develop competencies, practice discernment, and cooperate with others rather than passively waiting for miraculous rescue.[65]

Yet the narrative maintains space for supernatural elements—the angel's appearance, Paul's prophetic insight, the snake bite survival—demonstrating that divine providence includes both ordinary and extraordinary dimensions. The balance prevents reducing faith to either rationalized naturalism or superstitious supernaturalism, instead maintaining that God works through diverse means accomplishing purposes through both typical and atypical events.

Authentic Leadership in Crisis

As the earlier analysis demonstrated, Paul’s leadership throughout Acts 27 integrates prophetic authority, pastoral sensitivity, practical wisdom, and courageous action—all exercised from a position of formal powerlessness. This multi-dimensional model challenges both authoritarian approaches that demand unquestioning obedience and leaderless egalitarianism that assumes competent leadership emerges spontaneously. Contemporary communities can cultivate such integrated leadership that serves collective welfare through demonstrated competence and character rather than formal position alone.

Paul's leadership throughout Acts 27 provides paradigm for authentic authority emerging through competence, character, and divine empowerment rather than merely formal position. This model proves particularly relevant for contemporary discussions about religious leadership, organizational authority, and community formation.[66]

Paul's leadership style creates community rather than demanding individual followership. The meal scene demonstrates how authentic leaders facilitate collective participation and shared purpose rather than accumulating personal power. Paul's public thanksgiving creates moment of communal unity serving practical needs while maintaining spiritual witness, modeling leadership that serves community welfare rather than leader aggrandizement.

Embodied Practices in the Storm: Acts 27 and Communal Formation

If Acts 27 forms the imagination, it does so through bodies, not just ideas. Pittman’s focus on embodied practices invites a close look at what people actually do in this chapter and how those actions shape the community aboard the ship.

The first practice is communal discernment under pressure. The narrative repeatedly shows decisions being made in conversation: the centurion consults the pilot and the owner, sailors read the wind and the season, Paul offers warnings that initially go unheeded. These scenes are not merely stage directions; they expose the fault lines between different forms of authority. Technical skill, economic interest, and political power all speak, but they do not speak with one voice. The early decision to press on from Fair Havens despite Paul’s caution becomes a case study in what happens when certain perspectives are privileged and others dismissed. Pittman’s approach highlights how the text trains readers to pay attention to who is heard and who is ignored when communities choose a course in anxious circumstances.

A second practice is embodied solidarity. As the storm intensifies, the chapter draws repeated attention to the shared physical condition of those aboard: hunger, sleeplessness, and exhaustion. When Paul finally urges them to eat, he does not offer a slogan; he takes bread, gives thanks, and eats in front of them all. What might be overlooked as a simple narrative detail becomes, under Pittman’s lens, a critical moment of formation. The act of eating is public, visible, and communal. The text notes that “all” were encouraged and that “all” took food. Formation here is not simply about what individuals believe; it is about how a group’s shared practices of eating, watching, and laboring together can sustain life when there are no guarantees about outcomes.

A third practice is reordering value through embodied loss. The crew throws cargo overboard, discards tackle, and eventually loses the ship itself. These actions are expensive. Grain bound for Rome, hardware essential to navigation, and the vessel that carried them all are sacrificed for the sake of preserving lives. The narrative refuses to romanticize this. It is costly and chaotic. Yet the story quietly teaches that there are moments when communities must let go of significant material goods or cherished plans if they are to preserve one another. Pittman’s emphasis on counter-cultural imagination underscores how this chapter invites readers to reconsider what they are prepared to lose and what they are determined to protect when crisis hits.

A fourth practice is staying together when fragmentation is tempting. Several times, smaller groups attempt to peel away from the larger whole: sailors seek to escape in the lifeboat, soldiers consider killing the prisoners to prevent any from swimming away. Each of these gestures moves toward a familiar pattern in crisis: saving one’s own skin by abandoning responsibility for others. Paul’s interventions resist this pattern. He calls the centurion and soldiers back to a posture of shared risk, insisting that survival depends on remaining together. Pittman’s reading pushes communities to see in these moments a template for resisting fragmentation—whether institutional, relational, or economic—when stress is high and trust is thin.