The Gospel of Mark Cliffhanger: Lost, Added, or Intentional?

The Gospel of Mark ends with one of the most perplexing puzzles: while earliest manuscripts conclude abruptly at verse 16:8 with women fleeing the tomb in fearful silence, later manuscripts include either a brief "Shorter Ending" or extended "Longer Ending" featuring post-resurrection appearances and the famous snake-handling passage. Recent scholarship, particularly Claire Clivaz's MARK16 project, challenges assumptions by showing our earliest manuscript witnesses may not be independent, while Stanley N. Helton's research suggests Origen likely knew all three endings. Rather than viewing these variations as problems to solve, this manuscript tradition invites us to see Mark's conclusion as deliberately open-ended—a literary cliffhanger that transforms readers from passive observers into active participants, called to break the silence and bear witness themselves.

Greg Camp and Patrick Spencer

5/26/202527 min read

NOTE: This article was researched and written with the assistance of AI.

Key Takeaways from Mark's Ending

Multiple authentic endings: Mark's Gospel exists in three distinct versions—ending abruptly at 16:8 with fearful silence, the brief Shorter Ending affirming resurrection and mission, and the expanded Longer Ending (16:9-20) containing post-resurrection appearances and the controversial "snake handling" passage that continues to influence certain Pentecostal practices

Digital scholarship revolution: Claire Clivaz's MARK16 project uses high-resolution manuscript imaging to challenge traditional assumptions, revealing that Codex Sinaiticus and Vaticanus may represent a single scribal tradition rather than two independent witnesses, thus weakening the supposed early consensus for the 16:8 ending

Narrative intentionality vs. textual accident: Literary criticism suggests the abrupt 16:8 ending may be deliberate—forcing readers to become active participants in continuing the Gospel story rather than passive observers, with the women's fearful silence creating narrative space for the audience to step into the mission themselves

Pastoral embrace of complexity: Rather than viewing textual variants as threats to biblical authority, churches can treat Mark's multiple endings as gifts that demonstrate how early Christian communities wrestled faithfully with proclaiming the resurrection, offering rich opportunities for teaching about Scripture's living transmission through history

Introduction: Three Endings, One Gospel: Mark's Unresolved Finale

The Gospel of Mark ends in a way that has puzzled, unsettled, and inspired generations of readers. While the Gospels of Matthew, Luke, and John each offer detailed accounts of the risen Jesus appearing to his followers, Mark's Gospel—as preserved in its earliest manuscripts—closes on a strikingly different note. At Mark 16:8, the women flee the empty tomb, "trembling and bewildered," and say nothing to anyone "because they were afraid." There is no appearance of the risen Christ, no reunion with the disciples, no moment of resolution.

Yet not all manuscripts agree. Some include a few lines beyond verse 8—a brief "Shorter Ending" that quickly affirms Jesus' resurrection and the spread of the gospel. Others include a much longer conclusion, extending to verse 20, which recounts Jesus' post-resurrection appearances, his commissioning of the disciples, and a list of miraculous signs associated with believers. It is in this Longer Ending that we find the famous verse about picking up snakes and drinking poison without harm (Mark 16:18), a text that continues to shape the practices of certain Pentecostal groups in parts of Appalachia. In one tragic example, a Kentucky pastor died from a rattlesnake bite during a church service in 2015, convinced he was obeying a direct promise of Scripture.[1]

The differences among these endings are more than a matter of manuscript trivia. They touch the heart of Christian proclamation—what it means to declare Christ risen, and how the Gospel story is meant to be told. In this article, we will examine the primary endings of Mark's Gospel: the abrupt ending at 16:8, the brief Shorter Ending, and the expansive Longer Ending. We will consider the textual evidence behind them, explore how early Christians and later scribes received these passages, and reflect on what they mean for theology and Christian life today.

We will also bring to bear newer tools in biblical scholarship. The rise of digital access to ancient manuscripts allows us to see what scribes actually wrote—and what they left out. Literary approaches such as narrative criticism help us understand the function of the abrupt ending within the Gospel's dramatic structure. Reader-response criticism offers insight into how different audiences, from the second century to the present, have engaged these endings. By taking all of these into account, we can approach Mark's conclusion not merely as a problem to be solved, but as a window into the richness of early Christian faith and witness.

Fear, Silence, and Ancient Secrets: Mysterious Ending of Mark | Dr. Stanley N. Helton

Variant Endings of the Gospel of Mark

1. The Abrupt Ending at 16:8

The most striking and earliest attested version of Mark's Gospel ends with verse 8. After the women arrive at the tomb and encounter a young man who tells them that Jesus has risen and will meet the disciples in Galilee, we read:

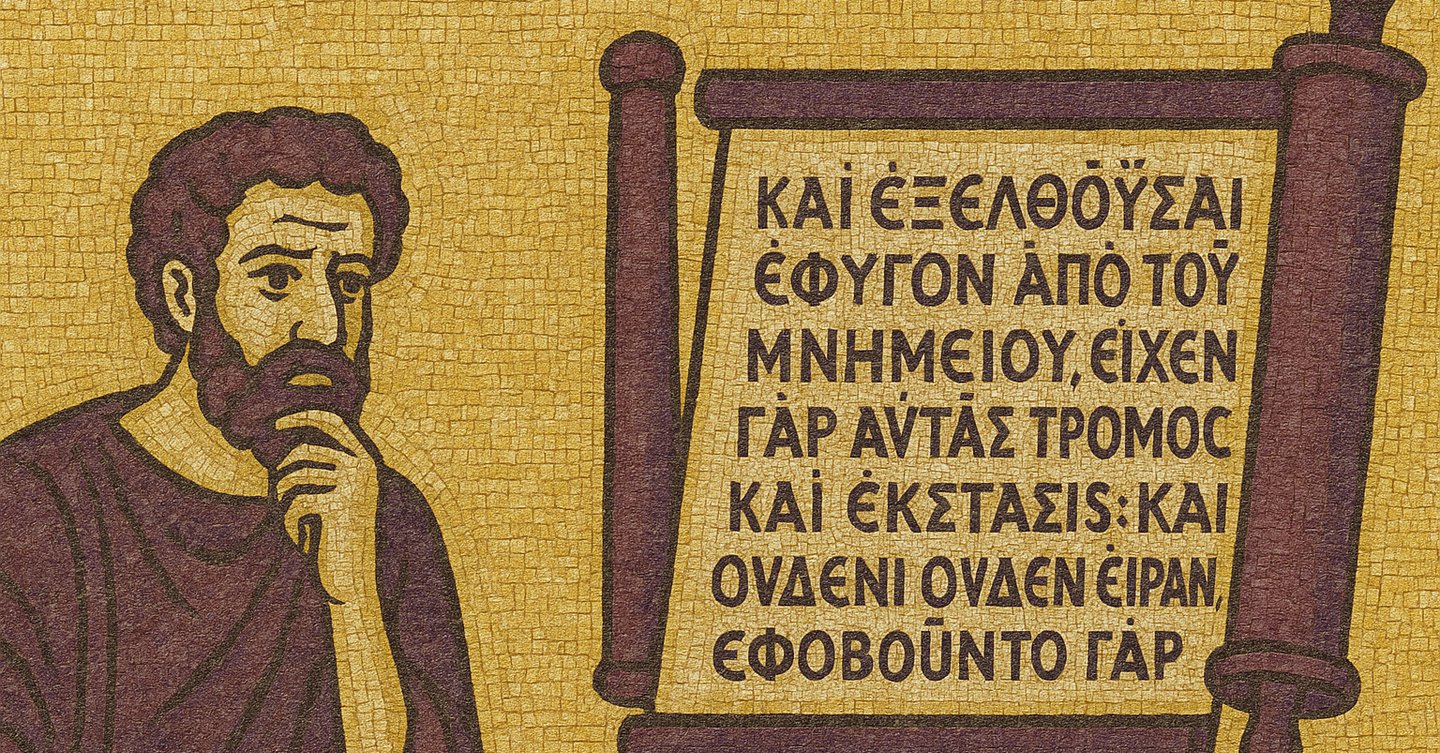

"So they went out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them; and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid."

(Mark 16:8, NRSV)

In the original Greek:

"καὶ ἐξελθοῦσαι ἔφυγον ἀπὸ τοῦ μνημείου, εἶχεν γὰρ αὐτὰς τρόμος καὶ ἔκστασις· καὶ οὐδενὶ οὐδὲν εἶπαν· ἐφοβοῦντο γάρ."

This ending has long drawn attention for its abruptness. Rather than concluding with joy, triumph, or clarity, it stops at a moment of fear and silence. What's more, the final word—"γάρ" (gar), typically translated "for"—is a conjunction that rarely ends a sentence in Greek literature. Some have suggested that this awkward construction indicates a missing ending, perhaps lost in transmission. Others argue that it was entirely deliberate—a literary move by Mark to provoke reflection, uncertainty, and response.[2]

From a literary perspective, this ending underscores themes that run throughout the Gospel: misunderstanding, fear, failure, and the unsettling nature of Jesus' mission. It leaves the reader with the weight of the message. If the women said nothing, who will? In this way, Mark's Gospel may be handing the story off to the audience, urging them to carry the news forward.[3]

2. The Shorter Ending

In a small number of manuscripts, the abrupt conclusion is followed by a brief paragraph sometimes referred to as the "Shorter Ending:"

"And all that had been commanded them they told briefly to those around Peter. And afterward Jesus himself sent out through them, from east to west, the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation."

This addition does not contain narrative detail but offers a summary statement of resurrection and mission. It appears to have been crafted to bring the story to a cleaner theological resolution, offering assurance that the message did, in fact, go forth.

Textually, the Shorter Ending is found in only a few manuscripts, including Codex Regius (8th century), and is often included alongside the Longer Ending. This pairing suggests that scribes were aware of the discomfort caused by the abrupt ending and tried to preserve both traditions. While the Shorter Ending lacks wide attestation and literary development, it reflects an early concern to provide closure and continuity with the preaching of the apostles.[4]

3. The Longer Ending (Mark 16:9–20)

By far the most well-known of the alternate conclusions is the Longer Ending, a twelve-verse section that appears in the majority of medieval Greek manuscripts and in many early translations of the New Testament.

This passage includes:

Jesus appearing first to Mary Magdalene

His appearance to two disciples walking in the country

A rebuke of the eleven disciples for their unbelief

The commissioning of the disciples to preach the gospel to all creation

A promise that signs will accompany believers, including speaking in tongues, casting out demons, and handling snakes

A final scene where Jesus ascends into heaven and the disciples go out and preach

Mark 16:9-20 (NRSV)

9 Now after he rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, from whom he had cast out seven demons.

10 She went out and told those who had been with him, while they were mourning and weeping.

11 But when they heard that he was alive and had been seen by her, they would not believe it.

12 After this he appeared in another form to two of them, as they were walking into the country.

13 And they went back and told the rest, but they did not believe them.

14 Later he appeared to the eleven themselves as they were sitting at the table; and he upbraided them for their lack of faith and stubbornness, because they had not believed those who saw him after he had risen.

15 And he said to them, “Go into all the world and proclaim the good news to the whole creation.

16 The one who believes and is baptized will be saved; but the one who does not believe will be condemned.

17 And these signs will accompany those who believe: by using my name they will cast out demons; they will speak in new tongues;

18 they will pick up snakes in their hands, and if they drink any deadly thing, it will not hurt them; they will lay their hands on the sick, and they will recover.”

19 So then the Lord Jesus, after he had spoken to them, was taken up into heaven and sat down at the right hand of God.

20 And they went out and proclaimed the good news everywhere, while the Lord worked with them and confirmed the message by the signs that accompanied it.

This ending brings Mark into closer alignment with the resurrection narratives of Matthew, Luke, and John, and it addresses the fear and silence of verse 8 by emphasizing proclamation, belief, and visible signs of divine power.

Patristic sources such as Irenaeus, writing in the late second century, quote from the Longer Ending, suggesting that it was in circulation relatively early.[5] At the same time, some early church fathers like Eusebius note that many copies of Mark ended at 16:8, and they question the authenticity of the additional verses.[6] The style and vocabulary of Mark 16:9–20 differ noticeably from the rest of the Gospel, which has led many scholars to conclude that it was not written by the original author of Mark.[7]

Despite these concerns, the Longer Ending has played a significant role in the life of the Church. It appears in the Latin Vulgate and was embraced in the Byzantine tradition. Even today, many Bibles include the passage, sometimes with footnotes or brackets. Its influence is felt in preaching, hymnody, and liturgy.

Whether seen as a faithful summary of apostolic teaching or a later attempt to resolve narrative tension, the Longer Ending remains a vital part of the discussion on how early Christians understood resurrection, mission, and the authority of Scripture.

What the Manuscripts Say: Key Textual Evidence

1. Earliest Manuscripts Ending at 16:8

When we examine the textual history of Mark's Gospel, the two most important early witnesses are Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus, both from the fourth century. These are considered among the most reliable and complete Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, and both conclude Mark's Gospel at 16:8.[8]

Codex Sinaiticus ends without any additional verses following the women's fearful flight from the tomb. There is no indication that verses were lost or removed. Codex Vaticanus also stops at 16:8, but its layout raises questions. Uncharacteristically, it leaves an entire blank column after verse 8 before beginning the Gospel of Luke. Since Vaticanus does not typically insert blank spaces between books, some scholars interpret this as a silent acknowledgement of an alternate ending that was known but not included.[9]

Claire Clivaz has raised a critical point about these two manuscripts. While most scholars have long treated them as independent witnesses to the 16:8 ending, Clivaz highlights evidence suggesting they may have been produced in the same scriptorium and possibly by the same scribe. If so, we may not be dealing with two early, independent attestations of the abrupt ending, but rather with a single textual tradition reproduced in two places. That shifts the evidential weight considerably and calls for greater caution when claiming that 16:8 represents the "original" ending based solely on these manuscripts.[10]

While the witness of Sinaiticus and Vaticanus is strong, it perhaps is not as conclusive as once believed. The blank column, the scribal commonalities, and the broader manuscript tradition suggest a more complex picture than a simple binary of early vs. late.

2. Absence of Papyri Evidence

When it comes to even earlier manuscript evidence, we must turn to the papyri. Unfortunately, the papyrus fragments of the Gospel of Mark that have survived do not preserve any portion of chapter 16. Papyrus 45 (P45), dating to the third century, includes material from all four Gospels, but the relevant portion of Mark is damaged or missing. Other early papyri, such as P84 or P137, either lack the end of the Gospel entirely or do not contain enough text to confirm or refute any of the endings.[11]

Some scholars have speculated that if Mark was originally written on a scroll rather than in codex form, the final portion may have been lost due to wear and tear at the end of the scroll. While this is a plausible theory, it remains unprovable. No existing manuscript, papyrus or otherwise, shows physical signs of a missing ending or truncation at precisely this point. The idea of a lost original conclusion, while intriguing, remains in the realm of conjecture.[12]

What we can say with confidence is this: the absence of any early papyrus support for Mark 16:9- 20, or even for 16:8, prevents us from making definitive claims about what the earliest copies contained. That silence should caution us against overstating the case on either side of the debate.

Argument from Style: A Nuanced Perspective

Recent computational analysis has provided a more nuanced understanding of Croy's stylistic arguments. Kelly Iverson's comprehensive study using the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae database examined 272 instances of γάρ followed by a period from the third century B.C.E. to the second century C.E., revealing that sentences ending with γάρ are "extremely, extremely rare at all times and in all genres."[13]

Rather than supporting either the mutilation theory or the intentional ending theory, this rarity suggests that "both the argument of frequency in selected genres and the use of γάρ as the concluding word in a piece of literature are moot points." The data can be "marshaled to argue for a hypothetical lost ending or the abrupt ending" with equal validity. This finding undermines arguments that rely solely on the grammatical peculiarity of the ending to determine Mark's original intent.

3. Manuscripts with the Longer and/or Shorter Endings

While the earliest manuscripts point to an abrupt conclusion, the vast majority of later manuscripts—from the fifth century onward—include additional material. Codex Alexandrinus, for example, a fifth-century Greek manuscript, contains the full Longer Ending without any marginal notes indicating concern. Codex Bezae, another important witness, also includes 16:9-20, though it is well known for its unique and paraphrastic tendencies.[14]

By the medieval period, the Longer Ending had become the standard conclusion to Mark, particularly within the Byzantine tradition. It was copied into nearly all Greek manuscripts, translated into Latin, Syriac, and Coptic versions, and incorporated into lectionaries and church readings.

Interestingly, some manuscripts include both the Shorter and Longer Endings, back to back. These composite texts suggest that scribes encountered divergent traditions and, rather than choosing one over the other, preserved both. In some cases, marginal notes acknowledge the disputed nature of the material. A few manuscripts even include asterisks or commentary indicating that some earlier copies ended the Gospel at 16:8.[15]

These scribal practices are instructive. They show that ancient copyists were not merely passive transmitters of text but active participants in a living tradition. Faced with uncertainty, many chose to preserve multiple endings, offering a layered witness to the evolving reception of Mark's conclusion.

Narrative Criticism and the Literary Function of Mark 16:8

From a narrative perspective, the Gospel of Mark ends not with resolution, but with rupture. The story that began with bold proclamation in the wilderness closes with trembling and silence. The women at the tomb receive the message of resurrection, but they flee and say nothing. This is no triumphant finale—it is a cliffhanger, a disruption, a challenge.

Mark's Gospel has long been recognized for its sharp pacing, abrupt transitions, and unsettling irony. Throughout the narrative, Jesus is misunderstood by his followers, opposed by religious leaders, and even abandoned in his final hours. The disciples—called to follow—repeatedly falter. The ending at 16:8 reinforces these themes. It exposes the cost of discipleship and the vulnerability of faith. Just when the good news reaches its climax, the witnesses fall silent.[16]

Literarily, this kind of ending forces the reader into the story. Mark doesn't show the resurrection; he announces it. The question is left hanging: if the women told no one, how did we come to hear the news? The answer is that the reader becomes the next link in the chain. Mark turns his audience into participants. The Gospel's final word—"for they were afraid"—is not the end of the story, but a pause that invites response.[17]

This reading aligns well with the broader themes of Mark: secrecy, reversal, struggle, and the mystery of Jesus' identity. It also allows us to see the Gospel not as unfinished, but as deliberately open-ended—an invitation to live out the message that the original witnesses were too afraid to proclaim.

Reader-Response Criticism: Interpreting Mark Across Time

If narrative criticism examines how the Gospel is written, reader-response criticism focuses on how it is received. Mark's abrupt ending places significant interpretive weight on the audience. The text does not tie up loose ends or offer reassurance. Instead, it demands engagement. Readers must decide what they believe, how they respond, and what they do with the message.

This ambiguity has not gone unnoticed across the centuries. Early Christian communities were clearly unsettled by the ending at 16:8. Some added a brief summary. Others expanded the story with appearances, commissions, and signs. These additions were not careless mistakes—they were sincere efforts by early readers to preserve the Gospel's power and coherence. In a sense, the Shorter and Longer Endings are forms of ancient reader-response, embedded directly into the manuscript tradition.[18]

Modern readers, too, often find Mark's ending difficult. In a culture shaped by narrative closure and happy endings, the silence of the women can feel anticlimactic or even troubling. Preachers may wonder how to teach a resurrection story without an actual resurrection scene. Teachers may worry about unsettling the faith of their students.

Yet this discomfort is itself a gift. It invites us to ask why we need closure. Why must resurrection be domesticated into certainty? Mark challenges us to consider that the power of the Gospel lies not in what is seen, but in what is promised. The risen Christ is not absent—he has "gone ahead of you into Galilee." The story continues, but not on the page. It continues in the life of the Church and the faith of the reader.

For pastors and teachers, this has rich implications. Rather than treating the variant endings as a problem to solve, we can present them as an opportunity to explore the many ways the Church has wrestled with the mystery of resurrection. We can invite congregations to enter the Gospel story—not just as readers, but as those called to bear witness, even in fear and trembling.

Cognitive Science of Narrative Gaps

Recent research in cognitive science offers a fresh perspective on Mark's ending that transcends the postmodern versus traditional interpretation debate. As Iverson demonstrates, the inferential processes required to make sense of Mark's abrupt ending are not modern innovations but reflect "cognitive processes that have been shaped through evolutionary development." The human brain evolved to "optimize inference making," developing what researchers call the "Inferential Brain Hypothesis."[19]

Studies of infant cognition show that even preverbal children can engage in "rudimentary probabilistic inference," suggesting that "the ability to determine 'the probability of uncertain future events' likely reflects an 'innate sensitivity' that has developed over millions of years". This research indicates that Mark's readers would have naturally engaged in what Iverson terms "predictive inference"—the cognitive process of imagining events beyond the narrative's conclusion.

The characteristics that typically trigger predictive inferences—narrative incoherence, contextual support for future events, and disrupted expectations—are precisely what Mark 16:7-8 provides. The angel's command creates an expectation that is immediately frustrated by the women's silence, forcing readers to mentally complete the narrative.

Claire Clivaz and the Digital Turn in Textual Criticism

One of the most significant developments in recent textual criticism is the increasing use of digital tools to access and reassess ancient manuscripts. Among the scholars leading this digital turn is Claire Clivaz, whose MARK16 project—funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation—has opened new doors for studying the diverse endings of the Gospel of Mark. The project's goal is to provide a virtual research environment that collects, visualizes, and analyzes the manuscript variations of Mark 16 in ways never before possible. In doing so, it brings renewed attention to the physical realities of the manuscripts themselves, not just the abstract text they transmit.[20]

Clivaz's work directly challenges the scholarly consensus that had solidified in the late twentieth century—namely, that Mark 16:8 represents the original and intentional conclusion of the Gospel. For decades, scholars had pointed to Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus as the strongest evidence for this view, both of which end Mark at verse 8 without including the Longer Ending. However, Clivaz urges us to look closer—and more concretely—at the manuscripts themselves. By examining high-resolution images and analyzing the scribal practices visible in these documents, she argues that these two codices may not represent two independent streams of tradition, as is often claimed. In fact, the same scribe may have been involved in producing both manuscripts, or at the very least, they were created in close proximity within the same scriptorium.[21]

This raises a critical question: If Sinaiticus and Vaticanus reflect the same editorial or scribal judgment, can they really be counted as separate witnesses in favor of 16:8? Clivaz thinks not. She points to features like the blank column at the end of Mark in Vaticanus—an anomaly in its otherwise continuous formatting—as evidence that the scribe was aware of additional material beyond verse 8 but chose to omit it. Rather than confirming the finality of 16:8, such features suggest ambiguity or uncertainty in the transmission process.[22]

Moreover, Clivaz contends that much of the older scholarship treated the text of Mark 16 as a purely literary or theological artifact—something to be read and interpreted, but not necessarily examined in its physical form. The digital availability of manuscripts now allows scholars and readers alike to engage directly with the "document" rather than just the "text." This is a subtle but significant shift. We are no longer confined to reading editions of the Greek New Testament or relying on secondhand descriptions of manuscript evidence. We can now see for ourselves where scribes left space, inserted marginal notes, or presented competing endings side by side.[23]

As Wido van Peursen notes, this "document-centered" approach transforms the way we do textual criticism. It allows us to recognize the scribes as active agents in the history of the text—interpreters who sometimes preserved multiple endings rather than suppressing one in favor of another. Through the lens of the MARK16 project, Clivaz has highlighted not only the complexity of the manuscript tradition but also the ways in which digital access empowers us to revisit long-held assumptions with fresh eyes.[24]

For pastors and lay leaders, the implications are clear. Textual decisions in our Bibles are not merely the product of ancient inspiration but also of historical transmission. By engaging both the theological and the material history of Mark's ending, we cultivate a deeper appreciation for Scripture as both sacred word and communal legacy.

What Digital Technology and Brain Research Tell Us About Mark's Ending

Clivaz's work with ancient manuscripts is just the beginning of a much bigger story. When scholars can examine high-resolution images of centuries-old biblical texts on their computers, they're not just looking at old documents—they're uncovering how people actually thought and processed stories two thousand years ago.

For decades, critics have dismissed people who accept Mark 16:8 as the real ending, calling their approach "postmodern"—basically accusing them of reading twenty-first-century ideas back into an ancient text. However, Kelly Iverson's cognitive research shows something remarkable: the mental processes that make Mark's abrupt ending work aren't modern at all. They're as old as humanity itself.[25]

When we read Mark 16:8 and feel compelled to imagine what happens next—when we mentally fill in the gaps about whether the women eventually told the disciples, whether Jesus met them in Galilee, whether the mission continued—we're using what brain scientists call "predictive inference." This isn't some sophisticated literary technique that requires a PhD to understand. It's how humans have always made sense of incomplete information, from figuring out whether that rustling bush might hide a predator to understanding that a friend's frown probably means something's wrong.

What's revolutionary about this discovery is that it suggests Mark knew exactly what he was doing. He wasn't writing an incomplete gospel that got cut off by accident or persecution. He was crafting an ending that would naturally trigger the same mental processes his first-century readers used every day to navigate their world. The combination of digital manuscript evidence and brain research is painting a picture of Mark as a sophisticated storyteller who understood human psychology in ways we're only now beginning to appreciate scientifically.

The implications of Clivaz's work extend beyond mere manuscript analysis. As Kelly Iverson notes in his cognitive science approach to Mark's ending, the digital turn has allowed scholars to move beyond viewing Mark 16:8 through purely postmodern literary lenses. Iverson argues that what critics have dismissed as "postmodern" interpretive strategies are actually rooted in ancient cognitive processes—specifically, the human capacity for "predictive inference" that has been shaped by evolutionary development. This intersection of digital manuscript study and cognitive science research suggests that Mark's abrupt ending may have been intentionally crafted to trigger inferential processes that are as ancient as human communication itself.

Origen's Witness to Multiple Endings: Stanley N. Helton's Analysis

While much of the scholarly discussion around the ending of Mark centers on manuscript evidence, patristic engagement with the text offers another essential layer of insight. One of the most intriguing figures in this regard is Origen of Alexandria (c. 185-254 CE), whose massive influence on Christian exegesis and textual scholarship makes his silence—or apparent silence—on Mark's ending especially noteworthy. In a detailed and thoughtful study, Stanley N. Helton revisits the traditional assumption that Origen was unaware of the Longer Ending and challenges the conclusions drawn from his supposed omission.[26]

For decades, prominent scholars such as Bruce Metzger cited Origen, along with Clement of Alexandria, as witnesses against the authenticity of Mark 16:9-20. The claim was simple: since Origen does not quote from the Longer Ending, he must not have known it. But as Helton points out, the argument from silence is fraught with difficulty—especially when it comes to someone like Origen, who worked with an extraordinary variety of textual sources.[27]

Helton makes a compelling case that Origen was familiar with all three endings associated with the Gospel of Mark: the abrupt ending at 16:8, the Shorter Ending, and the Longer Ending. His argument begins with a recognition of Origen's unparalleled philological expertise. Trained in Alexandrian grammatical traditions and equipped with an acute sensitivity to textual variants, Origen regularly compared multiple versions of biblical texts and meticulously noted differences. His monumental work, the Hexapla, arranged various Greek translations of the Old Testament in parallel columns alongside the Hebrew, often marking additions or discrepancies with diacritical symbols such as asterisks and obeli.[28]

In his commentaries and letters, Origen described this textual work in detail. He spoke of being compelled to stay up late, "studying and correcting the copies" (φιλολογεῖν καὶ ἀκριβοῦν τὰ ἀντίγραφα), and his method shows a level of care that few, if any, of his contemporaries could match. According to Helton, this meticulous attention to textual detail makes it highly unlikely that a passage as substantial as Mark 16:9-20 would have escaped his notice—especially given its use in some Christian communities during his lifetime.[29]

Indeed, Origen's exposure to multiple textual traditions means he likely encountered copies of Mark that ended at 16:8, as well as those that continued with one or both of the alternative endings. In some of his later work, Origen appears to align with textual traditions associated with Codex Θ, which included the Longer Ending without apparent objection. This further supports Helton's claim that Origen not only knew of the various endings but found nothing in them requiring correction or censure.[30]

What's more, Origen's commitment to preserving textual plurality—rather than forcing a uniform reading—sets a powerful precedent. Rather than eliminating variants he deemed questionable, he would often retain them with notations, trusting readers and scholars to weigh the evidence. This practice suggests that early Christians were not nearly as disturbed by textual differences as later modern interpreters have been. They were capable of holding multiple possibilities in tension without sacrificing their faith in the reliability of Scripture.[31]

Helton's study reminds us that the transmission of the New Testament was not a neat and tidy process but a living history shaped by theological concern, scribal decision, and interpretive community. Origen stands as a witness not only to the early state of the text but to a method of engagement that is both rigorous and charitable—open to complexity, attentive to detail, and deeply committed to the truth.

For today's church, Helton's reading of Origen offers a valuable lesson: fidelity to Scripture does not mean denying textual variation; it means being faithful in how we engage it. Whether Mark's Gospel ends at verse 8, 20, or somewhere in between, we are invited to hear in these variations the echo of a community wrestling with how best to proclaim that Jesus is risen.

Theological and Pastoral Implications

1. Resurrection Without Appearance?

At first glance, an ending without a resurrection appearance may seem theologically lacking. After all, the heart of Christian faith rests on the risen Christ. Yet Mark's Gospel, if it ends at 16:8, offers a powerful and perhaps even unsettling insight: the resurrection is not something to be contained in narrative or seen with one's eyes—it is something to be trusted, proclaimed, and lived.[32]

The absence of an appearance doesn't deny the resurrection. In fact, the young man at the tomb plainly declares, "He has been raised" (Mark 16:6). But Mark leaves the implications hanging in the air. The women, overwhelmed by fear and awe, flee in silence. It is an uncomfortable moment. And yet, it resonates with the core of Mark's theology. The Gospel has always portrayed disciples who struggle to understand, who fear, fail, and flee. Mark 16:8 is not out of place—it is the culmination of that tension.[33]

Seen this way, the ending calls the church to faith amid uncertainty. It insists that resurrection is not just an event to be witnessed but a truth to be trusted. The story isn't complete until it is embodied in the life of the disciple. In a world where faith is often tested by silence and fear, Mark's ending may be more relevant than ever.

2. Preaching and Teaching Disputed Texts

The presence of multiple endings in our manuscripts presents a real challenge for pastors and Bible teachers. Should we preach from Mark 16:9-20, knowing that many scholars consider it a later addition? Should we read 16:8 as the definitive ending, even when it feels incomplete?

The answer is not simple—but it is pastoral. First, congregations deserve to know the history of the text. Teaching the variation in Mark's ending does not undermine Scripture; it enhances our trust in the Spirit's work through the church. When we show that scribes, fathers, and translators wrestled with this ending for centuries, we invite people into the living tradition of faith seeking understanding.[324

Second, we can affirm that both endings—abrupt and expanded—carry theological value. The Longer Ending has nourished the church for generations, echoing the call to proclaim, baptize, and embody signs of God's power. The Shorter Ending, while brief, affirms the truth of resurrection and mission. And the ending at 16:8 calls us to faith in the silence.

When preaching or teaching from Mark 16, we can acknowledge the complexity while focusing on the core message: Christ is risen, and the mission continues.

3. Embracing Complexity in Scripture

Some may fear that textual variation invites doubt. But in truth, it invites deeper engagement. Scripture was not handed down as a single, flawless manuscript; it came to us through communities who preserved, copied, and passed it on with faith and care.[35]

The variations in Mark's ending are not flaws to be hidden but gifts to be explored. They remind us that the Gospel is not a static text but a living word, shaped by those who first believed it and carried forward by those who still do. This perspective can free pastors and teachers to approach Scripture not as a puzzle to be solved, but as a sacred conversation in which we are participants.

For lay leaders teaching Sunday school or leading Bible studies, this conversation offers a rich opportunity to model thoughtful faith. We can say, "Here's how early Christians handled this mystery. What does that teach us about our own calling?"

4. Implications for Modern Biblical Interpretation

The convergence of digital manuscript analysis, cognitive science research, and careful patristic study offers a more sophisticated understanding of Mark's ending than previous generations have possessed. Rather than viewing textual variation as a problem to be solved, we might follow Origen's example of "holding multiple possibilities in tension without sacrificing faith in the reliability of Scripture".

The cognitive dimension of Mark's ending suggests that the evangelist crafted his conclusion not as an incomplete accident but as a "structural device intended to generate a predictive inference." This process engages readers in "establishing coherence through the inferential process"—making them active participants in the story's completion.

This understanding transforms our approach to disputed texts from apologetic defensiveness to interpretive richness, recognizing that Mark's various endings represent not textual corruption but the living tradition of faith communities wrestling with the mystery of resurrection across the centuries.

Why Mark's Multiple Endings Matter

The ending of the Gospel of Mark invites us into a place of tension and possibility. Whether the Gospel closes with fearful silence at 16:8 or with triumphant proclamation in 16:9-20, we are left with a vital truth: the story continues—not just in manuscript traditions but in the life of the church.

Through the work of scholars like Clivaz, we see how digital access to ancient manuscripts is reshaping our understanding of textual history and challenging old assumptions. Through Helton's careful reading of Origen, we rediscover an early Christian leader who likely held all three endings in view—and found room for all of them in his exegetical practice.

Together, these voices remind us that faith is not threatened by complexity; it is refined by it. The Gospel of Mark, with all its ambiguity and brilliance, calls us not to settle for certainty but to step into the story ourselves. The tomb is empty. The risen Christ has gone ahead. And now it is our turn to bear witness.

Endnotes

[1] Peter Orr, “Where Does Mark End? Handling Snakes and Ancient Manuscripts,” May 9, 2023, https://www.desiringgod.org/articles/where-does-mark-end.

[2] J. David Hester, "Dramatic Inclusion: Irony and the Narrative Rhetoric of the Ending of Mark," Journal for the Study of the New Testament 17 (1995): 61-86, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0142064X9501705704; Mary Ann Tolbert, Sowing the Gospel: Mark’s World in Literary-Historical Perspective (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1989) 288-99, https://www.fortresspress.com/store/product/9780800629748/Sowing-the-Gospel-Mark-World-in-Literary-Historical-Perspective.

[3] J. Lee Magness, Sense and Absence: Structure and Suspension in the Ending of Mark's Gospel (SBL Semeia Studies; Atlanta: SBL Press, 1986), https://www.amazon.com/Sense-Absence-Structure-Suspension-Literature/dp/1555400078.

[4] Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 2nd ed. (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005), https://www.amazon.com/Textual-Commentary-Greek-Testament-Ancient/dp/1598561642.

[5] Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3.10.6, http://www.gnosis.org/library/advh3.htm.

[6] Eusebius, Ad Marinum, cited in Claire Clivaz, "The Ending of Mark 16:8 in Early Manuscripts," Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 95 (2019): 645-59, https://poj.peeters-leuven.be/content.php?url=article&id=3286928.

[7] Daniel B. Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Academic, 2008), https://www.amazon.com/Greek-Grammar-Beyond-Basics-Exegetical/dp/0310218950.

[8] Claire Clivaz, "The Ending of Mark 16:8 in Early Manuscripts," Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 95 (2019): 645-59, https://poj.peeters-leuven.be/content.php?url=article&id=3286928.

[9] Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 2nd ed. (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005), https://www.amazon.com/Textual-Commentary-Greek-Testament-Ancient/dp/1598561642.

[10] Claire Clivaz, "The Ending of Mark 16:8 in Early Manuscripts," Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 95 (2019): 645-59, https://poj.peeters-leuven.be/content.php?url=article&id=3286928.

[11] J.K. Elliott, New Testament Textual Criticism: The Application of Thoroughgoing Principles: Essays on Manuscripts and Textual Variation (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2014), https://www.amazon.com/New-Testament-Textual-Criticism-Thoroughgoing/dp/1628370289.

[12] Clayton N. Croy, The Mutilation of Mark's Gospel (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2003), https://www.abingdonpress.com/product/9780687052936/.

[13] Kelly R. Iverson, "A Further Word on Final γάρ (Mark 16:8)," CBQ 68 (2006): 79-94, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43725642.

[14] Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 2nd ed. (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005), https://www.amazon.com/Textual-Commentary-Greek-Testament-Ancient/dp/1598561642.

[15] J.K. Elliott, New Testament Textual Criticism: The Application of Thoroughgoing Principles: Essays on Manuscripts and Textual Variation (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2014), https://www.amazon.com/New-Testament-Textual-Criticism-Thoroughgoing/dp/1628370289.

[16] Camille Focant, The Gospel according to Mark: A Commentary, translated by Leslie Robert Keylock (Eugene, OR: WIPF and Stock Publishers, 2012), https://wipfandstock.com/9781610977630/the-gospel-according-to-mark/.

[17] J. David Hester, "Dramatic Inclusion: Irony and the Narrative Rhetoric of the Ending of Mark," Journal for the Study of the New Testament 17 (1995): 61-86, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0142064X9501705704.

[18] J.K. Elliott, New Testament Textual Criticism: The Application of Thoroughgoing Principles: Essays on Manuscripts and Textual Variation (Atlanta: SBL Press, 2014), https://www.amazon.com/New-Testament-Textual-Criticism-Thoroughgoing/dp/1628370289.

[19] Kelly R. Iverson, "A Postmodern Riddle? Gaps, Inferences and Mark's Abrupt Ending," JSNT 44:3 (2022): 337-67, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0142064X211049348.

[20] MARK16 Project, University of Lausanne, https://www.unil.ch/mark16.

[21] Claire Clivaz, "The Ending of Mark 16:8 in Early Manuscripts," Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 95 (2019): 645-59, https://poj.peeters-leuven.be/content.php?url=article&id=3286928.

[22] Clivaz, "The Ending of Mark 16:8 in Early Manuscripts," https://poj.peeters-leuven.be/content.php?url=article&id=3286928.

[23] Wido van Peursen, "Digital Text Edition and the Editor as Interpreter," in Digital Humanities and Biblical, Early Jewish and Early Christian Studies, ed. Claire Clivaz et al. (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 201-220.

[24] Claire Clivaz, "The Ending of Mark 16:8 in Early Manuscripts," Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 95 (2019): 645-59, https://poj.peeters-leuven.be/content.php?url=article&id=3286928.

[25] Kelly R. Iverson, "A Further Word on Final γάρ (Mark 16:8)," CBQ 68 (2006): 79-94, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43725642.

[26] Stanley N. Helton, "Origen and the Endings of the Gospel of Mark," Conversations With the Biblical World 36 (2016): 103-25, https://www.academia.edu/38107310/Origen_and_the_Endings_of_the_Gospel_of_Mark.

[27] Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 2nd ed. (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005), https://www.amazon.com/Textual-Commentary-Greek-Testament-Ancient/dp/1598561642.

[28] Helton, "Origen and the Endings of the Gospel of Mark," https://www.academia.edu/38107310/Origen_and_the_Endings_of_the_Gospel_of_Mark.

[29] Origen, Letter to Africanus, cited in Stanley E. Helton, "Did Origen Know the Longer Ending of Mark?" Vigiliae Christianae 71, no. 2 (2017): 105-125.

[30] Helton, "Origen and the Endings of the Gospel of Mark," https://www.academia.edu/38107310/Origen_and_the_Endings_of_the_Gospel_of_Mark.

[31] Origen, Commentary on Matthew, cited in Helton, "Origen and the Endings of the Gospel of Mark," https://www.academia.edu/38107310/Origen_and_the_Endings_of_the_Gospel_of_Mark.

[32] Joel Marcus, Mark 8--16: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, AB (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 1096.

[33] Camille Focant, The Gospel according to Mark: A Commentary, translated by Leslie Robert Keylock (Eugene, OR: WIPF and Stock Publishers, 2012), https://wipfandstock.com/9781610977630/the-gospel-according-to-mark/.

[34] James M. Robinson, The Gospel of Jesus: In Search of the Original Good News (New York: HarperOne, 2005), https://www.amazon.com/Gospel-Jesus-Search-Original-Good/dp/0060762179/ref=tmm_hrd_swatch_0.

[35] Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), https://www.amazon.com/Text-New-Testament-Transmission-Restoration/dp/019516122X.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on the Ending of the Gospel of Mark

Q1. Why does the Gospel of Mark end so abruptly at 16:8?

The earliest and most reliable manuscripts of Mark end at 16:8, with the women fleeing the tomb in fear and saying nothing to anyone. This abrupt ending lacks any post-resurrection appearances of Jesus, which has puzzled scholars and readers alike. Some argue this was due to a lost ending, while others believe Mark intentionally left the story open-ended. Literary and narrative critics suggest this "cliffhanger" compels the reader to step into the story—to become the one who proclaims the resurrection that the women initially did not.

Q2. What are the Shorter and Longer Endings of Mark, and where did they come from?

After verse 8, some manuscripts add either a Shorter Ending or a Longer Ending (verses 9–20). The Shorter Ending offers a brief theological summary affirming Jesus’ resurrection and mission. The Longer Ending includes resurrection appearances, a commissioning of the disciples, miraculous signs, and the ascension of Jesus. These additions likely emerged as early Christian responses to the discomfort with the Gospel's abrupt close, attempting to harmonize Mark with Matthew, Luke, and John.

Q3. How do scholars determine which ending is original?

Textual critics analyze ancient manuscripts like Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus—both of which end at 16:8. For decades, their agreement was considered strong evidence for the abrupt ending's authenticity. However, Claire Clivaz’s MARK16 project challenges this, showing that both codices may have been produced by the same scriptorium, possibly even the same scribe. This undermines the assumption of independent testimony and opens the door to re-evaluating the manuscript tradition as more complex and less conclusive.

Q4. Did early church fathers like Origen know about the other endings?

Stanley N. Helton’s research argues that Origen likely knew all three endings—16:8, the Shorter, and the Longer Ending. Origen was an expert in comparing manuscript traditions and frequently marked variants in his Hexapla. Though he does not explicitly quote the Longer Ending, Helton suggests that Origen’s scribal practice of retaining but marking variations shows a willingness to preserve divergent traditions rather than erase them. His silence may not be ignorance but rather discretion or theological focus.

Q5. What are the theological implications of Mark’s abrupt ending?

If Mark truly ends at 16:8, theologically it emphasizes trust over sight. The resurrection is announced, not shown. This invites readers into active participation—echoing the Gospel’s themes of discipleship, fear, and faith. From a pastoral standpoint, teaching these multiple endings doesn't weaken Scripture but deepens it. It shows how early Christians wrestled with mystery and affirms that Scripture's power lies not just in textual uniformity but in its lived interpretation across time and community.