What Happens in Luke 24: From Bewildered to Commissioned Disciples and Readers

Many pastors may be tempted to treat Luke 24 as mere transition to Acts, but they're dead wrong. This isn't just resurrection reporting—it's a masterclass in spiritual transformation that modern churches desperately need. Luke crafts three game-changing episodes: women dismissed as unreliable become first witnesses, dejected disciples experience burning hearts on Emmaus road, and terrified followers transform into bold commissioners. The anonymous Emmaus companion? That's YOU in the story. Jesus doesn't just appear—he systematically opens minds through Scripture, breaks bread for recognition, and establishes worship as mission foundation. Luke's "open closure" doesn't end the story; it launches readers into ongoing witness. For those seeking a message for the church, this isn't ancient history—it's your blueprint for moving people from confusion to confident faith through progressive revelation and community formation.

Greg Camp and Patrick Spencer

6/8/202528 min read

NOTE: This article was researched and written with then assistance of AI.

Key Takeaways from Luke 24

Literary function: Luke 24 operates as a masterful narrative climax that transforms characters from confusion to action through progressive revelation and "open closure" that simultaneously resolves Jesus's earthly ministry while initiating broader thematic development

Reader engagement strategy: The anonymous Emmaus disciple and threefold recognition pattern (failure to recognize, scriptural illumination, eucharistic revelation) create permanent "narrative space" for contemporary readers to experience their own interpretive journey within the biblical narrative

Theological framework: Sophisticated intertextual connections link the temple framing device (1:9 to 24:53) with prophetic fulfillment themes, demonstrating how Luke presents early Christianity as both continuous with and transcendent of Jewish religious tradition

Scholarly implications: The text depicts doubt in development while showing integration of scripture and ritual in group formation, with implications for leaders addressing questions in their communities

Critical significance: Recent narrative criticism reveals Luke's sophisticated understanding of how Gospel endings function as new beginnings, with textual variants reflecting early Christian theological debates about resurrection embodiment and ascension timing

Introduction: From Bewildered Disciples to Commissioned Witnesses

Luke 24 presents the climactic conclusion to Jesus's earthly ministry through three interconnected episodes: the women's discovery of the empty tomb (24:1-12), the Emmaus road encounter (24:13-35), and Jesus's final appearances and ascension (24:36-53). This chapter transforms confused disciples into assured reporters, establishing the foundation for actions described in Acts.

Picture the scene: two dejected disciples trudge along a dusty road from Jerusalem, their hopes crushed and their hearts heavy. Hours later, these same individuals race back to the Holy City with renewed understanding and urgent news. What happened on that seven-mile journey transforms not only their understanding but serves as a paradigm for every reader who encounters Luke's masterfully crafted Gospel conclusion.

The ending of Luke's Gospel, particularly chapters 24:13-53, represents far more than a simple historical account of post-resurrection appearances. It functions as both the climactic resolution to Jesus's earthly ministry and the foundational preparation for the continuing story of action and expansion in Acts.

In Summary: Luke's conclusion doesn't simply report what happened; it carefully orchestrates how readers experience the resurrection through progressive revelation, recognition scenes, and participatory narrative techniques. The disciples' transformation from bewildered followers to empowered figures mirrors the interpretive process in the narrative.

This article explores how Luke's Gospel ending masterfully transforms both characters and readers through divine initiative in recognition, intertextual echoes, and narrative closure that simultaneously opens new possibilities for action and extension. By examining the text through narrative criticism, reader-response theory, and text-critical analysis, we'll uncover how Luke creates space for contemporary readers to see themselves not as distant observers of ancient events, but as participants in the ongoing story of resurrection and extension.

Road to Recognition in Luke 24 | Interview with Dr. Joel B. Green

What Makes Luke's Gospel Ending So Powerful? The Literary Foundation

How Does Luke Connect His Gospel to Acts?

Luke's Gospel demonstrates remarkable narrative coherence, with multiple thematic threads converging in the final chapter to create profound resolution and new beginning. The journey motif that dominates Luke's central section (9:51-19:44) finds its ultimate completion not in Jerusalem's temple courts, but in the disciples' return to the city after their Emmaus encounter, preparing them for the expansion depicted in Acts.

The geographical framework proves crucial to Luke's theological vision that spans both volumes of his work. Jerusalem functions as both the culmination of biblical prophecy and the launching point for universal extension. Luke's "Jerusalem-centeredness" creates a narrative bridge between volumes, where the Gospel opens with Zechariah's temple service (1:8-23) and closes with the disciples' continual worship in the temple (24:53), positioning them exactly where Acts will begin with the promise of the Spirit and the birth of the church.[1]

What Scripture does Jesus explain in Luke 24? The fulfillment language from Luke's preface (1:1-4) reaches its climax in Jesus's post-resurrection exposition of "Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms" (24:44-47). Luke's claim to write an "orderly account" of "things fulfilled" (πεπληροφορημένων) finds its vindication as Jesus demonstrates how his suffering and resurrection align perfectly with Israel's Scriptures.[2] This scriptural fulfillment motif transforms the resurrection from an isolated miracle into the decisive moment when God's ancient promises reach their intended goal, while establishing the hermeneutical foundation for the apostolic preaching in Acts.

Joel B. Green's analysis reveals how this scriptural exposition functions as more than proof-texting; Jesus "re-narrates Israel's story through the lens of his death and resurrection," providing the theological framework that will enable the disciples to proclaim Christ to both Jews and Gentiles in Acts.[3] The comprehensive nature of this reinterpretation—encompassing Law, Prophets, and Psalms—equips the apostles with the interpretive tools necessary for their cross-cultural activity.

The narrative architecture also reveals Luke's sophisticated understanding of closure and openness. While resolving the central questions about Jesus's identity and action, the ending simultaneously opens the story beyond its textual boundaries through the promise of the Spirit (24:49) and the universal scope of proclamation to "all nations" (24:47). This technique, which scholars call "open closure," allows Luke to provide satisfying resolution while pointing readers toward their own participation in the continuing story that will unfold in Acts.[4]

How Does Character Development Work in Luke 24?

Luke's characterization strategy throughout the Gospel builds toward the climactic recognition scenes of chapter 24, positioning readers to experience transformation alongside the characters.[5] The disciples' persistent misunderstanding, documented throughout the narrative, creates dramatic tension that finds resolution through divine illumination rather than human achievement. This pattern begins early in the Gospel, where even those closest to Jesus struggle to comprehend his identity and mission (9:45; 18:34).

What role do women play in Luke's resurrection account? The women at the tomb (24:1-12) establish themes that will dominate the chapter while also prefiguring the broad reporting that characterizes Acts. Their initial perplexity gives way to remembrance as the angels remind them of Jesus's earlier predictions. Their role as first reporters—dismissed as "idle tales" (24:11)—establishes a pattern where those initially considered unreliable become the primary bearers of resurrection testimony.[6] This reversal of expectations serves Luke's broader theological vision of how God works through the marginalized and overlooked, a theme that will be crucial for understanding the Gentile expansion in Acts.

Mikeal C. Parsons' text-critical work reveals additional layers of meaning in these recognition scenes. The textual variants in Luke 24:51, particularly the phrase "and was taken up into heaven," create what he terms "interpretive spaces" where readers actively participate in meaning-making.[7] Some manuscripts omit the explicit ascension reference, while others include it, reflecting early Christian theological debates about the relationship between Jesus's earthly ministry and his continuing presence with the church.

The progressive revelation structure building to the climax demonstrates Luke's mastery of dramatic pacing while preparing readers for the episodic nature of Acts.[8] Each recognition scene in chapter 24 reveals more about Jesus's identity while maintaining elements of mystery and surprise. The women recognize that Jesus has risen but do not see him; the Emmaus disciples converse with Jesus without recognizing him until the crucial moment of bread-breaking; the gathered disciples see Jesus but initially mistake him for a spirit. This graduated revelation creates space for readers to participate in the disciples' journey from confusion to clarity while establishing patterns of divine revelation that will continue throughout Acts.

Character development in Luke 24 also reveals the democratizing nature of resurrection faith that will characterize the early church in Acts.[9] Unlike other ancient religious traditions that required extensive preparation or special qualifications for divine encounters, Luke presents recognition of the risen Christ as available to ordinary people in everyday circumstances. This accessibility becomes crucial for contemporary readers, particularly ministers and lay leaders who may feel inadequately prepared for spiritual leadership, while also establishing theological foundation for the diverse leadership that emerges in Acts.

What Do Textual Variants Reveal About Luke's Meaning?

Parsons' sophisticated text-critical analysis reveals how manuscript variants in Luke's ending affect both interpretation and preparation for Acts.[10] The most significant variants occur in Luke 24:50-53, where different manuscript traditions reflect early Christian debates about the timing and significance of Jesus's ascension. Some ancient witnesses, including Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Cantabrigiensis, omit the explicit reference to Jesus being "taken up into heaven," while the majority of manuscripts include it.

These textual decisions have profound implications for understanding the relationship between Luke and Acts. If the shorter reading is original, the emphasis shifts from Jesus's physical departure to the disciples' ongoing worship and praise, potentially creating a smoother transition to Acts 1:3-11 where the ascension is described in detail. If the longer reading is original, Luke 24 provides a compressed account that Acts 1 expands, emphasizing the theological significance of Jesus's departure for his continuing ministry through the church.

Parsons argues that these variants often reflect interpretive traditions that illuminate how early Christian communities understood and transmitted Luke's Gospel.[11] The textual evidence suggests that some communities emphasized the continuity of Jesus's presence through worship and Spirit-empowered mission, while others stressed the distinctiveness of his post-resurrection appearances before his ascension. Both traditions preserve important theological insights about the relationship between Jesus's earthly ministry and the church's continuing mission.

Western Non-Interpolations in Luke 24

Building on Parsons' analysis of ascension variants, another significant textual phenomenon in Luke 24 involves what are known as "Western non-interpolations"—a term coined by F.J.A. Hort to describe readings in Western text-type manuscripts (notably Codex Bezae and the Old Latin versions) that omit phrases or entire verses found in the majority of other Greek manuscripts, such as Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus.[12] What makes these omissions so striking is that, contrary to the usual tendency of the Western tradition to be more expansive or paraphrastic, these readings are notably shorter. Hort and others have argued that such omissions may preserve the original form of the text, suggesting that the longer readings in the Alexandrian (or so-called "Neutral") tradition are later interpolations—possibly added for theological emphasis or to harmonize with other Gospels.[13]

In Luke 24, several significant examples of these Western omissions appear:

Luke 24:3 -- Omits the phrase "of the Lord Jesus"

Luke 24:6 -- Omits "He is not here, but has risen"

Luke 24:12 -- Omits Peter's visit to the tomb

Luke 24:36 -- Omits or varies "and said to them, 'Peace be with you'"

Luke 24:40 -- Omits "And when he had said this, he showed them his hands and his feet"

Luke 24:51 -- Omits "and was carried up into heaven"

Luke 24:52 -- Omits "and they worshipped him"

These readings have long sparked debate among textual critics. On the one hand, external evidence clearly favors the longer versions, since they are supported by a wide range of early manuscripts, including Papyrus 75, which dates to the early 3rd century and contains many of the fuller readings. On the other hand, internal arguments—such as the principle of lectio brevior potior ("the shorter reading is preferable") and the tendency of scribes to expand texts for clarity, harmony, or Christological emphasis—make the Western omissions intriguing candidates for authenticity.[14]

For much of the 20th century, critical editions leaned toward omitting or bracketing these phrases as later additions. However, with growing scholarly respect for the Alexandrian tradition and manuscript discoveries like 𝔓75, most modern editions now retain the longer readings, though often with footnotes acknowledging the shorter Western variants. Yet scholars such as Jenny Read-Heimerdinger have challenged this consensus, arguing that the Western text, far from being a truncated or corrupt version, represents a deliberate literary edition that may preserve an earlier form of Luke's Gospel.[15]

Ultimately, these Western non-interpolations in Luke 24 underscore a central tension in textual criticism about how brevity and scribal tendencies interact with theological development. These variants continue to offer valuable insight into the transmission history of the Gospel of Luke while creating additional "interpretive spaces" where readers actively participate in meaning-making—exactly the kind of reader engagement that characterizes Luke's broader narrative strategy.

Who Was the Unnamed Disciple on the Emmaus Road?

The identity of Cleopas's companion on the Emmaus road has intrigued interpreters since the earliest centuries of Christianity, but the interpretive significance lies not in solving the mystery but in recognizing how the anonymity functions within Luke's broader narrative strategy spanning both volumes. Early traditions speculated about this figure—naming him Peter, Nathanael, or even Luke himself—while modern scholars like Sharon Ringe propose the companion could be Cleopas's wife, possibly connecting to John 19:25's "Mary of Clopas."[16]

However, Green's analysis reveals that the anonymity of Cleopas's companion exemplifies Luke's strategy of creating "narrative space" for reader identification that will prove crucial for understanding varied roles in Acts.[17] By leaving the disciple unnamed, Luke models a communal identity grounded in shared recognition of Christ rather than rigid hierarchy.[18] This technique invites readers to project themselves into the story, experiencing the journey from doubt to recognition as their own interpretive journey while preparing them to understand how the Spirit works through various unnamed believers in Acts.

For contemporary readers, this narrative invitation proves particularly powerful because it establishes patterns that continue throughout Acts. The unnamed disciple represents every believer who has walked away from Jerusalem—whether literally or metaphorically—carrying disappointment, confusion, or broken expectations about God's work in the world. The character's ordinariness removes barriers to identification that might exist with more prominent biblical figures, while establishing the theological foundation for understanding how God works through ordinary believers like those in Acts 6:1-7 or 11:19-26.

The anonymity also serves Luke's broad theological vision that spans both volumes.[19] The interpretive flexibility demonstrates how the text creates space for readers across cultures, centuries, and circumstances to find themselves within the biblical narrative, making the Emmaus story perpetually relevant for diverse communities of faith while prefiguring the cultural diversity that will characterize the church in Acts. This narrative openness establishes patterns for understanding how the gospel transcends ethnic and cultural boundaries.

Parsons' work on the "departure theme" in Luke-Acts reveals additional significance in the anonymity.[20] The unnamed companion represents the ongoing presence of Christ with his people even after his physical departure. Just as Jesus walks unrecognized with the disciples, he continues to accompany the church through the Spirit's presence in Acts, often working through unexpected agents of divine grace.

What is the Meaning of the Emmaus Road Story? How Luke 24:13-35 Models the Reader's Journey to Faith

Threefold Recognition Pattern

The Emmaus narrative follows a carefully structured threefold pattern that moves from concealment through revelation to recognition, providing a paradigm for how understanding develops in the narrative. This pattern—failure to recognize, scriptural illumination, and sacramental revelation—illustrates processes in development and practice while revealing Luke's sophisticated understanding of divine initiative in revelation.

Why don't the disciples recognize Jesus? (24:16) The failure to recognize serves both theological and literary functions. Green's analysis emphasizes that the disciples' eyes being "kept from recognizing" Jesus employs a passive voice construction (ἐκρατοῦντο) that suggests divine agency in the concealment.[21] This divine restraint mirrors earlier instances in Luke where understanding is withheld until the appropriate time (9:45; 18:34), creating a theological framework for understanding how God controls the timing and manner of revelation.

For contemporary readers, this acknowledgment of divine initiative provides insight for those experiencing uncertainty or confusion. Sometimes the inability to "see" God's presence reflects divine timing rather than personal failure. This insight proves relevant for those who may wonder why clear biblical teaching doesn't automatically produce transformation.

How does Jesus explain the Scriptures? (24:25-27)

The scriptural illumination provides the theological center of the recognition process. When Jesus "opens the Scriptures" (24:32), he employs the same "opening" (διήνοιξεν) language that appears throughout chapter 24—the disciples' "eyes were opened" at Emmaus (24:31) and their "hearts burned" as Jesus interpreted Scripture (24:32). This creates a progressive revelation pattern that validates Christian scriptural interpretation while establishing Jesus as the ultimate hermeneutical key to understanding all of Scripture.

Green's analysis reveals that Jesus doesn't merely "proof-text" messianic prophecies but "re-narrates Israel's story through the lens of his death and resurrection."[22] The phrase "beginning with Moses and all the Prophets" suggests comprehensive reinterpretation of Israel's scriptures through a Christological lens, offering a model for Christian biblical interpretation. This hermeneutical method will enable speakers like Stephen (Acts 7) and Paul (Acts 13:16-41) to demonstrate how Jesus fulfills Israel's scriptures while opening salvation to all nations.

For contemporary readers, this scene illustrates both method and process for biblical interpretation while establishing continuity with apostolic practice.[23] The method involves reading all of scripture in light of Christ's death and resurrection, finding connections between Old Testament texts and Christian faith that demonstrate God's consistent purposes across salvation history. The process comes from recognizing that even the risen Christ took time to explain the scriptures carefully—patient teaching and gradual illumination represent normal rather than deficient approaches to understanding.

What happens when Jesus breaks bread? (24:28-31)

The sacramental revelation completes the recognition pattern through communal encounter. Recent scholarship has demonstrated that the physical proofs Jesus offers—palpability and eating—were not absolute indicators of living versus ghostly status in ancient Mediterranean cultures.[24] Ancient texts describe various types of post-mortem apparitions, including disembodied spirits who could sometimes eat (like Odysseus's mother drinking sacrificial blood) and heroes whose graves were known yet who remained capable of physical contact with the living. The breaking of bread ties revelation to communal practice, prefiguring Acts' emphasis on table fellowship (Acts 2:42, 46) and creating a template for ongoing Christian worship. The moment of recognition occurs not during intellectual discussion but in the familiar gesture of breaking bread, suggesting that spiritual insight often emerges through embodied practices rather than abstract reasoning.

How Does Luke Prepare Readers for Acts? From Private Revelation to Public Proclamation

What biblical themes appear in the Emmaus story? The Emmaus narrative resonates with numerous Old Testament accounts of divine encounters, creating rich intertextual connections that deepen the story's theological significance while preparing readers for the cultural reversals in Acts. These echoes not only demonstrate Luke's sophisticated literary artistry but also provide contemporary readers with a broader biblical framework for understanding their own experiences.

The most prominent parallel connects to Genesis 18, where Abraham entertains three visitors without initially recognizing their divine identity. Both narratives feature travelers offering hospitality to strangers, meals that facilitate recognition, and the sudden disappearance of the divine visitor(s). This parallel suggests that divine encounters often occur through ordinary hospitality rather than extraordinary circumstances, establishing patterns that will prove crucial for understanding how the message spreads through household networks in Acts.[25]

Green's analysis reveals how this hospitality theme carries profound implications for understanding the cultural subversion that characterizes Luke's theology.[26] The Emmaus story redefines "redemption" not as militaristic liberation (24:21) but as reconciliation through suffering, challenging Greco-Roman patronage systems and political expectations. This redefinition will prove essential for understanding how the gospel challenges imperial ideologies throughout Acts while creating alternative communities based on mutual service rather than hierarchical domination.

Jewish traditions of unrecognized divine messengers provide additional context for understanding Luke's narrative strategy while preparing readers for the unexpected ways God works in Acts.[27] These traditions suggest that God frequently works through disguised or hidden presence rather than obvious revelation. This pattern offers comfort for believers who struggle to perceive God's activity in their circumstances while establishing theological foundations for understanding how God works through unexpected agents like Cornelius (Acts 10) or the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8).

The intertextual connections also include Psalm 116:9, where the psalmist speaks of walking "before the Lord in the land of the living." The Emmaus disciples literally walk with the risen Lord, fulfilling this ancient aspiration in unexpected ways while establishing templates for understanding the church's pilgrimage in Acts. Contemporary readers can understand their own spiritual journey as walking with the risen Christ, even when his presence remains unrecognized, while participating in the ongoing journey of the church through history.

The geographic symbolism reveals additional layers of meaning that connect to Acts. The seven-mile journey from Jerusalem to Emmaus represents what Green calls "spiritual dislocation," while the return to Jerusalem signifies "reintegration into the community of faith." This circular pattern will be repeated throughout Acts as believers are scattered by persecution but return to strengthen the central community, demonstrating how apparent departures from the center often lead to deeper appreciation for the gospel's truth and wider expansion of its influence.

How Does Jesus Overcome the Disciples' Fear?

The transition from the intimate Emmaus encounter to Jesus's appearance before the gathered disciples (24:36-43) marks a crucial shift in Luke's narrative strategy from private revelation to communal formation, while establishing patterns that will govern the church's development throughout Acts. When Jesus suddenly appears among the eleven and their companions with the greeting "Peace be with you," the disciples' terror and assumption that they see a ghost reflects the universal human struggle to comprehend resurrection reality that will continue to challenge believers throughout Acts.

Green's analysis emphasizes how Luke's careful attention to their emotional state—"startled and frightened"—provides psychological realism that validates rather than dismisses the difficulty of accepting extraordinary claims.[28] This realistic portrayal will prove crucial for understanding the mixed responses to apostolic preaching in Acts, where some believe immediately while others require additional proof or reject the message entirely. The disciples' fear models the kind of honest struggle that characterizes authentic faith development rather than superficial conversion.

Jesus's response to their fear demonstrates the theological significance of embodied resurrection for contemporary ministry and teaching while establishing foundations for understanding the church's material witness in Acts. The invitation to "touch me and see" (24:39) and the dramatic eating of fish (24:41-43) serve multiple narrative functions beyond mere apologetics. Parsons' work reveals how these physical demonstrations establish both proof of physicality and preparation for the Eucharistic community that will characterize the early church in Acts.[29]

Contemporary scholarship has shown that Luke's resurrection account engages with diverse ancient traditions of post-mortem appearances—from disembodied spirits to reanimated corpses to translated mortals—without being confined to any single model. The characteristics Luke applies to Jesus draw from all these traditions while transcending their limitations. This literary strategy creates a portrait of the resurrected Jesus that surpasses expected modes of post-mortem appearances by incorporating elements from multiple traditions while establishing something entirely new.

The theological implications of embodied ministry extend beyond personal comfort to fundamental questions about Christian witness in contemporary contexts. If the risen Christ required physical proof to overcome his disciples' fear, contemporary Christian communities must grapple with how to provide tangible evidence of resurrection reality in their own contexts. This challenges churches to demonstrate gospel values through concrete actions, creating communities where divine love becomes physically manifest through care for others, approaching ministry with the same patience and understanding Jesus showed toward struggling disciples.

For contemporary ministers and lay leaders, this scene provides crucial guidance for addressing doubt and fear within congregations while preparing them to understand the community formation strategies in Acts. Luke's portrayal reveals that even those closest to Jesus struggled with resurrection faith, yet their doubt did not disqualify them from receiving commission and empowerment.[30] This offers profound encouragement for church leaders who may feel inadequate due to their own questions or uncertainties, while establishing patterns for understanding how the Spirit works through imperfect vessels throughout Acts.

The communal dimension of this encounter establishes patterns that will prove crucial for understanding the church's development in Acts.[31] The movement from individual fear to corporate recognition models how authentic Christian community emerges when members share both struggles and celebrations without fear of judgment. The disciples' corporate encounter strengthens individual faith while creating bonds that will sustain them through the persecutions and challenges described in Acts.

What Happens When Jesus Opens Their Minds to Understand Scripture?

The climactic moment of understanding in Luke 24:44-45 represents the hermeneutical center of Luke's Gospel while providing crucial guidance for contemporary biblical interpretation and teaching. When Jesus "opened their minds to understand the Scriptures," Luke employs the same "opening" (διήνοιξεν) language that appears throughout chapter 24, creating a progressive revelation pattern that establishes Jesus as the ultimate hermeneutical key to understanding all of Scripture.

The reference to "the Law of Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms" represents Luke's comprehensive hermeneutical program that will prove essential for apostolic preaching to both Jewish and Gentile audiences. This threefold division reflects first-century Jewish understanding of scriptural authority while simultaneously claiming that all biblical texts find their fulfillment in Jesus's death and resurrection.

Luke's emphasis on divine initiative in opening minds (διήνοιξεν τὸν νοῦν αὐτῶν) provides crucial theological insight about the role of the Holy Spirit in biblical interpretation.[32] Contemporary teachers and ministers cannot simply assume that clear explanation will automatically produce spiritual understanding. The same divine power that enabled the disciples to comprehend Scripture's meaning must be sought through prayer and dependence on the Spirit's illuminating work.

What Is Luke's Version of the Commission?

Luke's version of the directive (24:47-48) differs significantly from Matthew's more familiar formulation, reflecting Luke's distinctive theological emphases while providing unique insights for contemporary analysis. The instruction to proclaim "repentance for forgiveness of sins to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem" encapsulates Luke's theological geography where Jerusalem functions as both the city of rejection and the birthplace of universal proclamation.

Green's analysis reveals how the phrase "beginning from Jerusalem" carries profound implications for understanding strategy and cultural engagement.[33] Rather than avoiding places where the gospel has been rejected or where reporting faces hostility, Luke's model suggests that action often begins precisely in such challenging contexts. This provides insight for those working in increasingly secular or hostile environments.

The specification of the disciples as "observers of these things" (24:48) emphasizes the experiential basis of testimony while providing guidance for contemporary reporting and sharing. Luke's observers don't merely transmit theological propositions but testify to personal encounters with the risen Christ. This transforms reporting from argument to testimony, from debate to storytelling, and from intellectual persuasion to relational encounter.

The promise of power from on high (24:49) creates narrative tension that requires resolution in Acts 2, demonstrating Luke's sophisticated understanding of development and preparation. The disciples must "stay in Jerusalem" until they receive divine empowerment, suggesting that effective action requires more than good intentions or theological knowledge—it demands transformation and divine enablement.

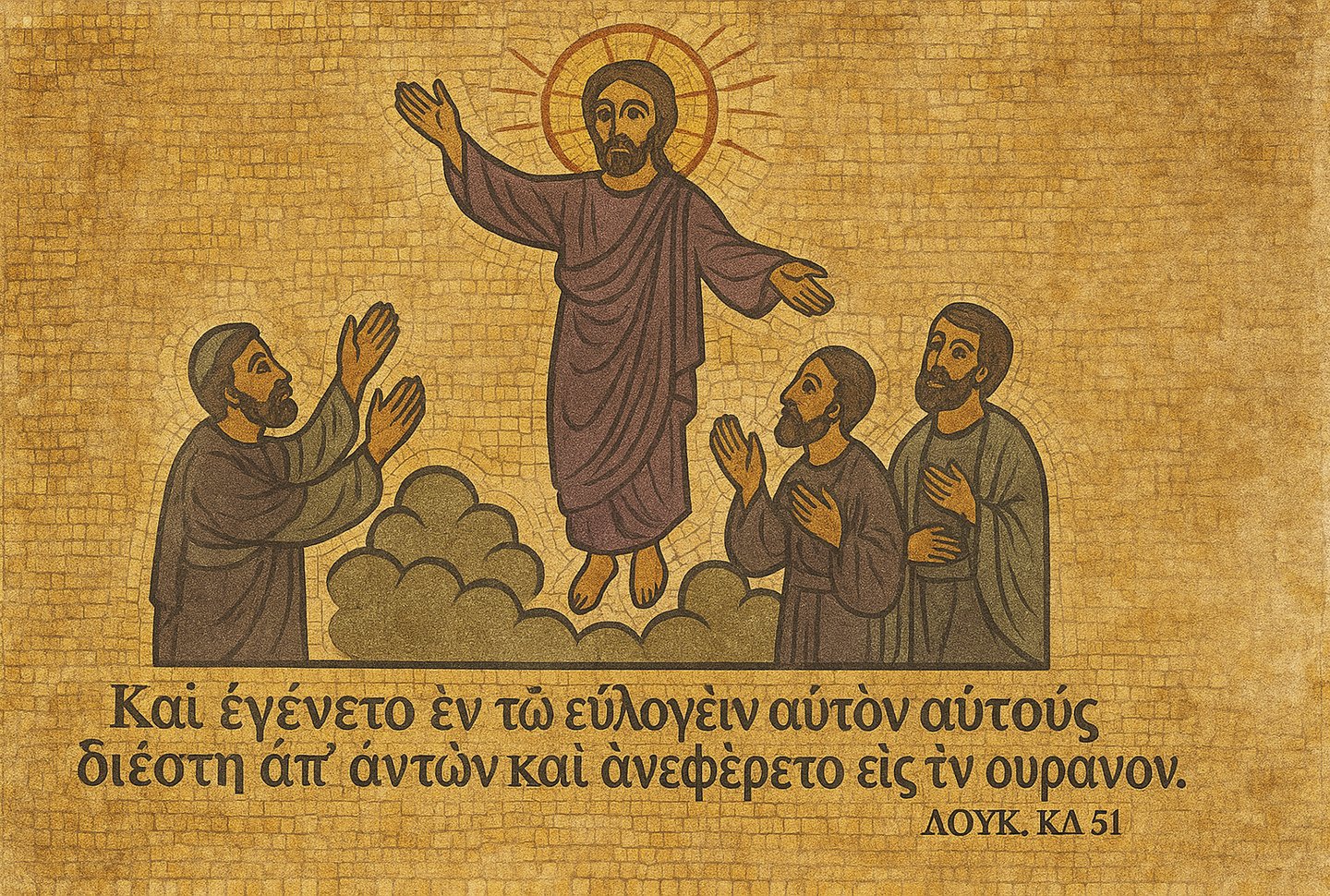

Why Is the Ascension Important in Luke? The Ascension: Closure That Opens New Possibilities

Luke's ascension account serves a crucial literary and theological function that has been clarified by recent narrative analysis of the two ascension accounts in Luke-Acts. The ascension in Luke 24:50-53 focuses on the disciples' recognition of Jesus's divine status, while Acts 1:9-11 emphasizes their preparation as authoritative witnesses. This dual presentation demonstrates Luke's sophisticated narrative strategy where one event serves different purposes within each volume.

The geographical specification of Bethany as the location for Jesus's final blessing and ascension (24:50) carries profound theological significance that illuminates Luke's understanding of Jesus's continuing ministry while establishing the transition to Acts. Bethany functions as liminal space between Jerusalem's particularistic focus and the world's universalistic mission, representing a threshold location that reinforces the narrative's theological movement from Jewish particularity to Gentile inclusion.

The ascension employs the literary genre of "rapture" stories, which in ancient literature always required witnesses to validate that the departed person was truly gone—since unlike death, there was no body left behind as proof. This genre choice supports Luke's emphasis on the disciples as credible witnesses while connecting Jesus's departure to biblical figures like Elijah, whose ascension similarly empowered his successor Elisha for continuing ministry.

Parsons' analysis of the "departure theme" reveals how the ascension serves multiple functions crucial for understanding Luke-Acts unity. The ascension represents both the culmination of Jesus's earthly ministry and the enablement of his continuing work through the Spirit-empowered church. This "departure" paradoxically enables greater presence, as Jesus's physical absence allows for his spiritual presence throughout the world via the church's mission in Acts.[34]

Jesus's act of blessing the disciples represents the assumption of permanent priestly role that extends beyond his earthly ministry into the church age described in Acts. The blessing gesture evokes Jewish liturgical traditions, particularly the Aaronic benediction (Numbers 6:24-26), while the ongoing nature of the blessing ("while he was blessing them") suggests continuing priestly intercession rather than concluded earthly ministry.

How Does Luke Connect Joy and Temple Worship?

The disciples' return to Jerusalem "with great joy" and their continual presence in the temple (24:52-53) creates Luke's most significant structural element—the temple inclusio that begins with Zechariah's temple service (1:9) and ends with disciples "continually in the temple" praising God. This framework demonstrates Christianity's continuity with Jewish worship while simultaneously transcending traditional boundaries through the resurrection.

The transformation from fear to joy represents more than emotional change; it reflects fundamental reorientation of the disciples' understanding of God's purposes and their role within salvation history. Their joy emerges not from personal happiness but from recognition that God's ancient promises have found fulfillment in ways that exceed their expectations. This theological joy provides a model for contemporary Christian communities seeking authentic worship that celebrates God's faithfulness while anticipating future hope.

The specification of "continual" temple worship establishes worship as the community's defining activity rather than merely one program among many, while providing the immediate context for the Spirit's outpouring in Acts 2. Luke's emphasis suggests that authentic Christian community emerges from shared recognition of God's grace expressed through corporate praise. Their worship becomes the foundation for action, demonstrating how authentic reporting flows from genuine encounter with God rather than religious duty or institutional obligation.[35]

Formation Patterns and Community Development

What Does Luke 24 Teach About Individual and Communal Transformation?

The threefold recognition pattern in the Emmaus narrative provides a template for understanding how insight develops. The movement from concealment through scriptural illumination to sacramental revelation suggests that transformative encounters with Christ emerge through the intersection of textual study and communal fellowship. This integration proves crucial for understanding how authentic character formation occurs through both individual study and corporate engagement.

Key Formation Insights:

Divine timing governs revelation: Sometimes inability to perceive the divine reflects timing rather than personal failure

Scripture as interpretive key: Textual understanding requires seeing all passages through the lens of Christ's death and resurrection

Community practices enable recognition: Shared meals and worship create contexts for encountering the divine

Gradual illumination is normal: Patient teaching and progressive understanding characterize healthy development

Embodied practices matter: Physical actions and tangible expressions demonstrate resurrection reality

Acknowledgment of doubt: Even those closest to Jesus struggled with resurrection acceptance

How Should Contemporary Readers Approach Biblical Interpretation?

The interpretive methods depicted in Luke 24:44-47 illustrate processes for contemporary analysis and teaching. Jesus's comprehensive exposition of "Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms" demonstrates that effective biblical interpretation requires showing how individual passages connect to the overarching narrative of divine redemptive work.

Analytical Applications for Study:

Attend to Narrative and Socio-Historical Context. Begin with the literary placement and cultural setting. Explore how the narrative reflects both first-century messianic expectations and the early Christian community's process of theological reorientation after the crucifixion.

Highlight Intertextual Echoes That Reframe Israel's Story. Trace how the narrative draws on the Hebrew Scriptures—not as proof texts, but as interpretive anchors. Jesus' exposition "beginning with Moses and all the prophets" (24:27) models a hermeneutic of rereading tradition in light of unexpected outcomes.

Emphasize the Theological Reframing of Hope and Restoration. Rather than reinforcing triumphalist resurrection motifs, Luke 24 calls for analytical restraint: the risen Christ is unrecognized, even elusive. Analysis should foreground this narrative tension and explore how theological meaning is constructed through ambiguity, memory, and reinterpretation.

Draw Out the Communal and Liturgical Dimensions. The recognition of Jesus "in the breaking of the bread" (24:35) suggests that theological insight arises not in isolation but through shared practice. Study might explore how interpretive clarity emerges through communal participation rather than individual certitude.

Approach Interpretation as Participatory, Not Possessive. Luke 24 resists closed theological conclusions. The disciples' "burning hearts" (24:32) reflect an interpretive process that is affective, partial, and ongoing. Readers should engage in a participatory hermeneutic—where understanding is shaped by shared questioning, remembrance, and openness to continued re-reading.

What Patterns Does Luke Establish for Community Formation?

The emphasis on community formation through shared meals, scriptural interpretation, and corporate worship provides practical guidance for contemporary leaders seeking to build authentic fellowship. The progression from private revelation to public proclamation demonstrates how personal experience must find validation and extension through communal engagement.

Community Formation Principles:

Shared recognition builds authentic fellowship: Community emerges when members experience Christ together

Worship as foundation for action: Corporate praise enables effective witness rather than merely preparing for it

Integration of Word and Sacrament: Biblical study and communal meals create contexts for encountering Christ

Inclusive leadership models: The unnamed Emmaus companion represents how the divine works through ordinary individuals

What Sustains Luke's Vision of Ongoing Mission?

The promise of continuing divine presence transforms the commission from impossible burden to sustainable calling. The disciples' mixed response of worship and doubt models realistic development while the assurance of divine presence provides sustenance for challenging activity. Contemporary readers can engage Luke's challenging vision precisely because it depends ultimately on divine presence and power rather than human capability and determination.

Most importantly, Luke's ending prepares readers for the continuing story that unfolds in Acts while establishing their role as participants rather than mere observers. The geographical movement from Jerusalem to Emmaus and back positions the disciples exactly where Acts will begin—in Jerusalem, empowered by the Spirit, ready to witness to the ends of the earth.

Bottom Line: Luke 24:13-53 functions as both satisfying conclusion and essential preparation, providing closure to Jesus's earthly ministry while establishing the theological, hermeneutical, and thematic foundations for the community's worldwide witness. Contemporary readers interested in biblical analysis can find in this masterful ending not merely ancient history but continuing invitation—to engage with the risen Christ through Scripture and sacrament, to experience transformation through divine grace rather than human effort, and to participate in the ongoing narrative that extends from Jerusalem to the ends of the earth.

Frequently Asked Questions About Luke 24

1. Why didn't the disciples on the Emmaus road recognize Jesus immediately?

Luke deliberately employs divine passive voice constructions (the disciples' eyes were "kept from recognizing" Jesus) to emphasize that the divine controls the timing and manner of recognition. This isn't about the disciples' failure but about divine initiative in revelation. For contemporary readers, this offers insight during seasons of difficulty—sometimes our inability to perceive divine presence reflects timing rather than personal inadequacy.

2. How does Luke 24 specifically prepare readers for the Book of Acts?

Luke 24 functions as essential preparation for Acts through several key elements: the directive's geographical framework ("to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem") establishes the expansion pattern that organizes Acts; the promise of Spirit empowerment (24:49) creates narrative tension resolved in Acts 2; Jesus's comprehensive scriptural exposition (24:44-47) provides the hermeneutical foundation for apostolic proclamation throughout Acts; and the disciples' positioning in Jerusalem creates the exact starting point where Acts begins.

3. What is the significance of the anonymous companion on the Emmaus road?

The anonymity of Cleopas's companion serves Luke's reader-engagement strategy by creating "narrative space" for contemporary readers to project themselves into the story. Rather than being a historical puzzle to solve, the unnamed disciple represents every person who has walked away from Jerusalem—literally or metaphorically—carrying disappointment or confusion about divine activity. This narrative technique removes barriers to identification while establishing patterns for understanding how the divine works through ordinary people.

4. How should contemporary readers use Luke 24's approach to biblical interpretation?

Luke 24 establishes crucial hermeneutical methods through Jesus's exposition of "Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms." Rather than proof-texting individual verses, Jesus "re-narrates Israel's story through the lens of his death and resurrection," providing a comprehensive christological reading strategy. For contemporary analysis, this means: attending to narrative and socio-historical context; highlighting intertextual connections that reframe rather than merely predict; emphasizing theological reframing of hope through suffering; drawing out communal and liturgical dimensions; and approaching Scripture as participatory rather than possessive.

5. What does the "threefold recognition pattern" teach about development?

The Emmaus narrative's structure—failure to recognize, scriptural illumination, sacramental revelation—provides a template for understanding how insight develops through the intersection of textual study and communal fellowship rather than individual effort alone. Key insights include divine timing in revelation, Scripture as interpretive key, community practices enabling recognition, gradual illumination as normal development, and embodied practices demonstrating resurrection reality.

6. Why is Luke's "open closure" significant for contemporary analysis?

Luke's ending technique provides satisfying narrative resolution while simultaneously opening new possibilities for ongoing interpretation. Rather than offering a completed program to mechanically implement, Luke presents a dynamic vision requiring contextual application. The directive to report "to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem" establishes both geographical framework and thematic imperative, calling contemporary readers to engage Luke's transformative narrative in their own cultural contexts while maintaining theological continuity with apostolic themes.

Luke 24 Discussion Questions

Narrative Technique and Reader Engagement: The article suggests that the unnamed disciple on the Emmaus road creates "narrative space" for contemporary readers. How does this literary device function across different cultural and religious contexts? What are the implications of this technique for how we understand ancient texts and their ongoing relevance?

Recognition and Revelation Patterns: Luke 24 follows a three-fold pattern: failure to recognize, scriptural illumination, and communal revelation. How might this pattern reflect broader human experiences of understanding and transformation? Where do we see similar patterns in other religious or philosophical traditions?

Hermeneutical Approaches: The article distinguishes between "proof-texting" individual verses and "re-narrating" an entire tradition through new interpretive lenses. How do different religious and academic communities approach the reinterpretation of foundational texts? When is such reinterpretation legitimate, and when might it be problematic?

Text and Community: The movement from individual encounter to communal formation raises questions about the relationship between personal religious experience and institutional religious life. How do different faith traditions balance individual insight with communal authority and interpretation?

Embodied vs. Abstract Knowledge: The emphasis on physical proofs (eating, touching) rather than purely intellectual arguments suggests different ways of knowing. How do various philosophical and religious traditions understand the relationship between embodied experience and intellectual truth?

Literary Closure and Ongoing Interpretation: The concept of "open closure" suggests texts that provide resolution while remaining open to continued interpretation. How does this literary technique appear in other ancient or modern texts? What are the implications for how religious communities relate to their foundational documents?

Historical Context and Contemporary Application: The article situates Luke 24 within first-century Jewish debates about afterlife beliefs. How do we balance historical-critical understanding of ancient texts with their contemporary significance across different religious and cultural contexts?

Authority and Interpretation: The text presents questions about who has authority to interpret scripture and how interpretive traditions develop. How do different academic disciplines and religious communities approach questions of interpretive authority? What role should scholarly expertise play in public discourse about religious texts?

Endnotes

[1] David Andrew Smith, "The Jewishness of Luke-Acts," Journal of Theological Studies 73:1 (2022): 45-78, https://doi.org/10.1093/jts/flab042.

[2] Loveday Alexander, "The Preface to Luke's Gospel: Luke 1:1-4; Acts 1:1," New Testament Studies 40:1 (1994): 78-103, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0028688500019068.

[3] Joel B. Green, The Gospel of Luke, New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), 845-851.

[4] Daniel Marguerat, "The End of Acts (28:16-31) and the Rhetoric of Silence," in Rhetoric and the New Testament: Essays from the 1992 Heidelberg Conference, ed. Stanley Porter and Thomas Olbricht (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993), 74-89.

[5] Joel B. Green, The Gospel of Luke, 853-857.

[6] Michal Beth Dinkler, "Silent Statements: Narrative Representations of Speech and Silence in the Gospel of Luke," Journal of Biblical Literature 136:4 (2017): 877-898, https://doi.org/10.15699/jbl.1364.2017.1.

[7] Mikeal C. Parsons, The Departure of Jesus in Luke-Acts: The Ascension Narratives in Context (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1987).

[8] Mikeal C. Parsons, The Departure of Jesus in Luke-Acts.

[9] Robert C. Tannehill, The Narrative Unity of Luke-Acts: A Literary Interpretation, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986-1990), 1:280-295.

[10] Parsons, The Departure of Jesus in Luke-Acts.

[11] Parsons, The Departure of Jesus in Luke-Acts.

[12] F. J. A. Hort, The New Testament in the Original Greek (Cambridge: Macmillan, 1881).

[13] Hort and Westcott, The New Testament in the Original Greek, vol. 2, Introduction and Appendix (Cambridge: Macmillan, 1882), 175-177; Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 4th ed. (Stuttgart: United Bible Societies, 2006), 162-165.

[14] Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament, trans. Erroll F. Rhodes, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), 280-281; Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 165.

[15] Jenny Read-Heimerdinger, The Bezan Text of Acts: A Contribution of Discourse Analysis to Textual Criticism, Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series 236 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002); see also Josep Rius-Camps and Jenny Read-Heimerdinger, A Reading of the Acts of the Apostles: The Text of Codex Bezae with an Introduction and Notes, 4 vols. (London: T&T Clark, 2004-2009).

[16] Heidi J. Hornik and Mikeal C. Parsons, "Naming the Unnamed (Luke 24:18): The Companion of Cleopas in Text and Image," Perspectives in Religious Studies 50 (2023): 223-46.

[17] Green, The Gospel of Luke, 859-862.

[18] Green, The Gospel of Luke, 845-851.

[19] Craig A. Evans, "Jesus and the Continuing Exile of Israel," in Jesus and the Restoration of Israel: A Critical Assessment of N. T. Wright's Jesus and the Victory of God, ed. Carey C. Newman (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1999), 77-100.

[20] Parsons, The Departure of Jesus in Luke-Acts.

[21] Green, The Gospel of Luke, 859-862.

[22] Green, The Gospel of Luke, 845-851.

[23] François Bovon, Luke 3: A Commentary on the Gospel of Luke 19:28-24:53, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2012), 384-394.

[24] Deborah Thompson Prince, "The 'Ghost' of Jesus: Luke 24 in Light of Ancient Narratives of Post-Mortem Apparitions," Journal for the Study of the New Testament 29:3 (2007): 287-301.

[25] Green, The Gospel of Luke, 859-862.

[26] Green, The Gospel of Luke, 845-851.

[27] Jacob Jervell, The Theology of the Acts of the Apostles (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 41-52.

[28] Green, The Gospel of Luke, 859-862.

[29] Parsons, The Departure of Jesus in Luke-Acts.

[30] Joshua W. Jipp, Christ Is King: Paul's Royal Ideology (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2015), 187-205.

[31] James D.G. Dunn, Baptism in the Holy Spirit (London: SCM Press, 1970), 38-54.

[32] Joshua L. Mann, "What Is Opened in Luke 24:45—the Mind or the Scriptures?" Journal of Biblical Literature 135:2 (2016): 349-365, https://doi.org/10.15699/jbl.1352.2016.3.

[33] Green, The Gospel of Luke, 845-851.

[34] Parsons, The Departure of Jesus in Luke-Acts.

[35] Dennis Hamm, "Joy and the Acts of the Apostles," Word & World 15:4 (1995): 398-404.

Bibliography

Alexander, Loveday. "The Preface to Luke's Gospel: Luke 1:1-4; Acts 1:1." New Testament Studies 40:1 (1994): 78-103. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0028688500019068.

Bovon, François. Luke 3: A Commentary on the Gospel of Luke 19:28-24:53. Hermeneia. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2012.

Bucur, Bogdan. "Blinded by Invisible Light: Revisiting the Emmaus Story (Luke 24,13-35)," Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 90:4 (2014): 685-707.

Green, Joel B. The Gospel of Luke. New International Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997.

Heidi J. Hornik and Mikeal C. Parsons, "Naming the Unnamed (Luke 24:18): The Companion of Cleopas in Text and Image," Perspectives in Religious Studies 50 (2023): 223-46.

Mann, Joshua L. "What Is Opened in Luke 24:45—the Mind or the Scriptures?" Journal of Biblical Literature 135:2 (2016): 349-365. https://doi.org/10.15699/jbl.1352.2016.3.

Marguerat, Daniel. "The End of Acts (28:16-31) and the Rhetoric of Silence." In Rhetoric and the New Testament: Essays from the 1992 Heidelberg Conference, edited by Stanley Porter and Thomas Olbricht, 74-89. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993.

Parsons, Mikeal C. The Departure of Jesus in Luke-Acts: The Ascension Narratives in Context. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1987.

Prince, Deborah Thompson. "The 'Ghost' of Jesus: Luke 24 in Light of Ancient Narratives of Post-Mortem Apparitions." Journal for the Study of the New Testament 29:3 (2007): 287-301.

Ross, William A. "'٢Ω ανόητοι κα'ι βραδείς τη καρδ٤α”' Luke, Aesop, and Reading Scripture," Novum Testamentum 58 (2016): 369-79.

Smith, David Andrew. "The Jewishness of Luke-Acts." Journal of Theological Studies 73:1 (2022): 45-78. https://doi.org/10.1093/jts/flab042.

Tannehill, Robert C. The Narrative Unity of Luke-Acts: A Literary Interpretation. 2 vols. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986-1990.

Troftgruben, Troy M. "The Ending of Luke Revisited," Journal of Biblical Literature 140:2 (2021): 325-46.