When Prosperity Breeds Prophets: Economic Exploitation in 8th-Century Israel

The 8th-century BCE prophets Amos, Hosea, Micah, and Isaiah emerged during ancient Israel's economic golden age to critique systematic exploitation of the poor. Archaeological evidence from residential architecture, luxury goods, and agricultural installations confirms their descriptions of extreme wealth concentration, with approximately 2% controlling vast estates while displacing subsistence farmers through debt foreclosure and land consolidation. These prophets functioned as political economists who understood how legal mechanisms enabled wealth transfer from peasants to urban elites, demonstrating that economic oppression, sexual exploitation, and political corruption operated as mutually reinforcing systems violating covenant principles of justice and communal solidarity.

Greg Camp and Patrick Spencer

10/8/202528 min read

NOTE: This article was researched and written with the help of AI.

Key Takeaways

Archaeological validation: Material evidence from 8th-century Israel and Judah confirms prophetic descriptions of extreme social stratification, with residential architecture, luxury goods, and agricultural installations demonstrating that approximately 2% of the population controlled vast wealth while the majority lived in significantly reduced circumstances—validating prophetic critiques as accurate social analysis rather than mere moral rhetoric

Economic sophistication: The prophets functioned as sophisticated analysts of political economy who understood specific mechanisms of exploitation including debt foreclosure procedures, land consolidation practices, commercial fraud techniques, and judicial corruption—demonstrating detailed knowledge of how legal and economic systems enabled systematic wealth transfer from small farmers to urban elites

Integrated exploitation systems: The prophets recognized that economic oppression, sexual violation, and political corruption functioned as mutually reinforcing problems rather than isolated moral failures—with debt-driven land loss creating conditions for sexual exploitation while corrupted judicial systems legitimized both, revealing how Baal worship provided ideological justification for arrangements that prioritized elite extraction over communal welfare

Cultural-material methodology: Marvin Chaney's integration of textual criticism with Gerhard Lenski's ecological-evolutionary theory and Avraham Faust's quantitative archaeological analysis demonstrates how advanced agrarian societies develop predictable patterns of wealth concentration and peasant displacement—providing frameworks for understanding both ancient conditions and their contemporary parallels

Covenant alternative: The prophetic vision of economic relationships based on mutual service, family tenure security, and community solidarity provides theological resources for contemporary religious communities seeking alternatives to competitive capitalism, challenging assumptions about inevitable inequality while maintaining hope for economic systems that prioritize human flourishing over wealth concentration

The 8th century BCE witnessed unprecedented economic transformation in ancient Israel and Judah, creating massive wealth inequality that triggered the emergence of classical Hebrew prophecy. Archaeological evidence reveals systematic land consolidation, agricultural intensification, and social stratification that the prophets Amos, Hosea, Micah, and Isaiah condemned as covenant violations. This article integrates archaeological findings, textual analysis, and comparative social science to examine how prophetic voices responded to economic injustice during Israel's most prosperous era. The evidence demonstrates that these prophets weren't merely religious reformers but sophisticated analysts of political economy who connected material conditions to spiritual authenticity, establishing theological foundations that remain relevant for contemporary discussions of economic justice and religious responsibility.

Introduction: When Prosperity Creates Prophets

The 8th century BCE marked ancient Israel's golden age of economic prosperity and political power. Under Jeroboam II's reign (793-753 BCE), the Northern Kingdom achieved unprecedented territorial expansion and commercial success. Archaeological evidence reveals massive construction projects, sophisticated administrative systems, and extensive trade networks that made Israel one of the ancient Near East's most developed societies.

Yet this same period produced Hebrew Scripture's most powerful voices of social criticism. Prophets Amos, Hosea, Micah, and Isaiah emerged not despite this prosperity but because of it, offering systematic critiques of the economic transformation that created extreme wealth inequality. Their messages weren't abstract theological speculation but concrete responses to observable social conditions that archaeological excavations have now documented in remarkable detail.

This convergence of material prosperity and prophetic protest raises fundamental questions about the relationship between economic development and social justice. How did agricultural intensification and trade expansion create the conditions that the prophets condemned? What specific mechanisms enabled wealthy elites to accumulate vast estates while displacing traditional subsistence farmers? How did these material transformations challenge covenant traditions that emphasized economic equality and social solidarity?

Recent archaeological research has provided unprecedented insight into 8th-century social stratification through systematic analysis of settlement patterns, residential architecture, and material culture.[1] When combined with methodologies that integrate textual criticism with agrarian sociology, this evidence reveals the prophets as sophisticated analysts of political economy whose theological insights emerged from careful observation of social transformation.[2]

The integration of archaeological evidence with prophetic literature demonstrates that these ancient voices addressed challenges that remain remarkably contemporary. The mechanisms of debt-driven land consolidation, the transformation of subsistence agriculture into export-oriented latifundia, and the corruption of legal systems by wealthy elites represent patterns that transcend historical boundaries. Understanding how the 8th-century prophets analyzed and responded to these conditions provides valuable insights for contemporary religious communities grappling with economic inequality and social justice.

Historical Context: The Foundation for Transformation

Late 9th-Century Recovery and Expansion

The economic transformation that shaped 8th-century Israel began during the late 9th century as regional political dynamics created unprecedented opportunities for expansion and prosperity. The Aramean kingdom of Damascus, which had dominated the region under Hazael's aggressive leadership, suffered devastating defeat when Assyrian king Adad-nirari III conquered Damascus in 796 BCE. This intervention removed the primary military threat that had constrained Israelite expansion for decades.[3]

The biblical account in 2 Kings 13:7 describes how Aramean pressure had reduced Israel's military forces to "fifty horsemen, ten chariots, and ten thousand foot soldiers," comparing the destruction to "dust at threshing time." Archaeological evidence from sites like Dan and Hazor confirms extensive destruction layers from this period, followed by impressive rebuilding phases that demonstrate the scale of recovery during the early 8th century.[4]

This regional power vacuum coincided with Assyrian preoccupation on other frontiers, allowing both Israel and Judah to pursue aggressive territorial expansion without immediate imperial interference. The demographic and economic recovery that followed created the foundation for the agricultural intensification and commercial development that would characterize Jeroboam II's reign.

Assyrian Imperial Context and Economic Opportunities

The Assyrian Empire's expansion under Tiglath-Pileser III (745-727 BCE) created both opportunities and constraints that shaped Israelite economic development. While Assyrian military pressure would eventually destroy the Northern Kingdom in 722 BCE, the earlier period of imperial expansion actually facilitated economic growth through integration into larger trade networks and access to distant markets.[5]

Assyrian administrative efficiency created standardized weights and measures, developed road systems, and established security for long-distance commerce that benefited client states like Israel. The Samaria Ostraca, administrative documents from the mid-8th century, reveal how the Israelite kingdom developed sophisticated bureaucratic systems for managing agricultural surplus and coordinating regional trade.[6]

However, this integration came at significant cost through heavy tribute obligations that required systematic extraction of agricultural surplus from the peasant population. The pressure to generate tribute payments accelerated the transformation from subsistence farming to cash crop production while creating incentives for land consolidation that would prove central to prophetic critiques of social injustice.

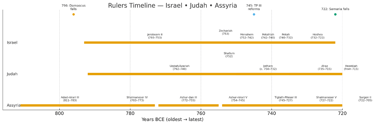

Table 1: Eighth Century BCE Ruler Timeline.

Methodological Foundations: Integrating Text and Material Culture

Understanding 8th-century prophetic literature requires methodological approaches that integrate multiple types of evidence. This section establishes the analytical frameworks employed throughout this study, demonstrating how textual criticism, archaeological analysis, and comparative social science create more comprehensive interpretations than any single approach alone.

Cultural-Material Methodology

Marvin Chaney's cultural-material methodology has revolutionized biblical scholarship's approach to economic analysis through integration of textual criticism with comparative sociology and archaeological evidence. His work represents a paradigm shift from purely literary approaches toward comprehensive analysis that treats prophetic literature as sophisticated political economy rather than merely religious exhortation.[7]

Chaney's application of Gerhard Lenski's ecological-evolutionary theory to ancient Palestine provides robust frameworks for understanding social stratification in advanced agrarian societies. Lenski's theory posits that human societies are fundamentally shaped by relationships among population, production, and environment, with technological advancement and resource distribution serving as primary drivers of sociocultural evolution.[8]

The ecological-evolutionary model identifies specific patterns in advanced agrarian societies that directly correspond to conditions described by 8th-century prophets. Such societies typically develop sharp social stratification, with wealth concentrated among a small elite while the majority live at subsistence levels. The theory predicts that technological advances in agriculture and administration create opportunities for surplus extraction, leading to land consolidation and peasant displacement—precisely the conditions critiqued by prophets like Amos and Micah.[9]

Chaney's analysis of debt instruments and land tenure transformation reveals specific mechanisms that created peasant poverty while concentrating wealth among urban elites. His examination of ancient Near Eastern legal practices demonstrates how traditional kinship-based economic relationships gave way to class-based exploitation through legal innovations that maintained technical legitimacy while undermining covenant principles.[10]

Archaeological Integration and Social Scientific Analysis

The integration of archaeological evidence with biblical texts requires careful methodological guidelines that respect both the independence of material evidence and the literary integrity of prophetic texts. Recent advances in archaeological methodology have created unprecedented opportunities for testing and refining historical reconstructions.[11]

Settlement pattern analysis examines the distribution, size, and organization of ancient sites across geographic regions to identify patterns of political control, economic specialization, and social stratification. Applications to 8th-century Palestine reveal clear differences between northern and southern kingdoms in terms of urban hierarchy, administrative organization, and economic integration.[12]

Avraham Faust's systematic approach to material culture analysis demonstrates how architecture, pottery, and small finds function as reliable indicators of social stratification and economic relationships. His quantitative methods enable comparison across sites and periods while providing objective measures of wealth concentration and social inequality. Faust's "inequality index" quantifies differences in house size, construction quality, and material assemblages to create measurable indicators of social stratification.[13]

The application of cross-cultural studies from comparative agrarian societies enhances understanding of ancient economic relationships while avoiding anachronistic assumptions. Studies of traditional agricultural societies provide models for understanding how pre-industrial economies functioned, how social stratification developed, and how economic transformation occurred.[14]

Contemporary methodological advances enable more sophisticated analysis of prophetic literature within its proper historical and social context. The integration of archaeological evidence with textual criticism creates opportunities for testing hypotheses about ancient economic conditions while respecting the integrity of both material and literary sources.[15]

Biblical-Theological Foundations: Exodus, Land, and Covenant Law

The 8th-century prophets' economic critiques cannot be properly understood apart from Israel's foundational narratives and legal traditions. The Exodus story, Pentateuchal land distribution principles, and covenant law codes provided the theological framework that made prophetic social criticism both intelligible and authoritative to their audiences. These traditions established three essential principles: God's deliverance from oppression as the paradigm for justice, land as divine gift held in conditional trust, and economic relationships governed by covenant rather than market logic.

Exodus as Justice Paradigm

The Exodus narrative functioned as Israel's defining foundational mythology, particularly for the Northern Kingdom. This was not merely historical memory but a theological template establishing that divine justice fundamentally opposes economic oppression. When Hosea declared "I am יהוה your God from the land of Egypt" (Hosea 12:9, 13:4), he reminded Israel that their covenant relationship originated in God's intervention against exploitative power structures.[16]

The prophets consistently invoked this liberation story to condemn contemporary injustices. Amos's radical reinterpretation declared: "You only have I known of all the families of the earth; therefore I will punish you for all your iniquities" (Amos 3:2).[17] The very election that Israel assumed guaranteed blessing became the basis for heightened accountability. God's past liberation from Egyptian slavery established the standard by which Israel's treatment of the vulnerable would be judged.

Hosea employed marriage imagery to connect Exodus theology with land fertility, portraying Israel's idolatry as spiritual adultery with direct consequences for agricultural productivity. When Israel served Baal instead of יהוה, God threatened to "destroy the productivity of the land" and turn "vines and fig trees to pristine forest" (Hosea 2:12).[18] This linkage between covenant faithfulness and land blessing, rooted in Exodus theology, would be formalized in Deuteronomy's covenant structure.

Land as Conditional Divine Grant

The Pentateuchal land laws established a fundamental principle that undergirded all prophetic economic critique: "The land is mine, and you are strangers and my tenants" (Leviticus 25:23). This theology of divine ownership meant that land was not merely property but covenant inheritance tied to Israel's faithfulness.[19] The prophets' condemnation of land consolidation drew directly from this foundational understanding.

The Jubilee legislation in Leviticus 25 was designed to prevent permanent economic stratification. Every 50th year, all leased or mortgaged lands were to return to original family owners, and all debt slaves were to be freed. This system ensured that "everyone had access to the means of production, whether the family farm or simply the fruits of their own labor."[20] The cyclical land restoration acknowledged that economic inequality, even when arising through seemingly legitimate transactions, violated covenant principles.

The story of Naboth's vineyard (1 Kings 21) provided a paradigmatic example of proper land tenure understanding. When King Ahab demanded Naboth's ancestral vineyard, Naboth refused: "The Lord forbid that I should give you the inheritance of my fathers" (1 Kings 21:3). This incident became a reference point for 8th-century prophetic condemnation of royal and elite land acquisition, demonstrating that even monarchical power could not legitimately override family inheritance rights.[21]

Covenant Law and Economic Justice

The Pentateuchal legal codes established specific protections for economically vulnerable populations that the prophets would later cite when condemning contemporary practices. Deuteronomy 19:14's prohibition against moving boundary markers became a metaphor for any theft of ancestral inheritance. The sabbatical and Jubilee year provisions demonstrated God's concern for preventing permanent poverty through systematic debt relief and land restoration.[22]

Isaiah's condemnation of those who "add house to house and join field to field" (Isaiah 5:8) directly referenced these land tenure principles. Micah's critique of those who "covet fields and houses and take them away; they oppress householder and house, people and their inheritance" (Micah 2:1-2) employed legal terminology that assumed audience familiarity with Pentateuchal property law.[23] The prophets weren't introducing novel economic theories but applying established covenant principles to contemporary violations.

Blessing and Curse Framework

The covenant blessing and curse formulas in Leviticus 26 and Deuteronomy 28 provided the theological framework through which the prophets interpreted Israel's social crisis. These texts outlined systematic reversals of divine promises that would occur if Israel proved unfaithful: agricultural failure instead of abundant harvests, population decline instead of multiplication, military defeat instead of victory, and ultimately exile from the promised land.[24]

The prophets employed this established framework to explain contemporary conditions. Hosea's "return to Egypt" motif (Hosea 8:13; 9:3) represented not just physical exile but theological regression to pre-covenant status—the ultimate reversal of redemption.[25] This imagery connected directly to Deuteronomy 28:68's warning that disobedient Israel would be sent back to Egypt, treating covenant violation as undoing the foundational liberation narrative.

Isaiah's Song of the Vineyard (Isaiah 5:1-7) employed this blessing-curse framework through agricultural imagery. The carefully tended vineyard producing only "wild grapes" represented Israel's failure to produce the "good fruit" of justice (מִשְׁפָּט) and righteousness (צְדָקָה). Instead of these covenant virtues, there was bloodshed and cries of distress—the anticipated curses for covenant violation.[26]

Prophetic Application and Development

The 8th-century prophets developed remnant theology based on these covenant promises and curses. While the majority would experience judgment through exile, God would preserve a faithful remnant to fulfill covenant purposes. Isaiah spoke of a remnant that would "return to the mighty God" (Isaiah 10:21), while Micah promised God would "gather the remnant of Israel" (Micah 2:12).[27] This theology maintained covenant continuity even through national catastrophe.

The prophets also projected covenant restoration into an eschatological future where proper land relationships would be restored. Micah's vision of people sitting "under their own vine and fig tree" without fear (Micah 4:4) represented the ideal fulfillment of Jubilee principles—everyone enjoying secure access to productive land.[28] This eschatological hope maintained the possibility of transformation while acknowledging current covenant failures.

Rather than innovating entirely new concepts, the 8th-century prophets applied foundational Pentateuchal traditions to their contemporary context. The Exodus provided the paradigm of divine justice that exposed Israel's oppression of the vulnerable. The land laws established principles of economic justice and divine ownership that condemned land grabbing and exploitation. The covenant blessing and curse formulas provided the theological framework for understanding both judgment and hope. Their messages cannot be adequately understood apart from this rich theological foundation, which provided both the criteria for judgment and the vision for restoration.

Table 2: Land Theology (Torah → Prophetic Applications)

Archaeological Evidence: Material Culture and Social Stratification

Settlement Patterns and Demographic Transformation

Archaeological surveys reveal that 8th-century Northern Israel supported approximately 350,000 inhabitants, making it the most densely populated region in the ancient Levant.[29] This demographic concentration required sophisticated agricultural systems and administrative coordination that archaeological evidence documents through settlement hierarchy, storage facilities, and processing installations.

Settlement pattern analysis reveals a well-developed rank-size distribution with clear distinctions between administrative centers, market towns, and agricultural villages. This hierarchical organization reflects the centralized control necessary for managing surplus extraction and redistribution on the scale required for tribute payments and elite consumption.[30]

Comparative analysis with contemporary Judah reveals significant differences in settlement organization. While Judah developed a "primate city" pattern dominated by Jerusalem, Northern Israel maintained multiple administrative centers including Samaria, Megiddo, Hazor, and Dan. This distributed administrative structure enabled more efficient surplus collection while creating multiple centers of elite consumption documented through luxury goods and monumental architecture.

Material Indicators of Wealth Concentration

Systematic analysis of residential architecture provides comprehensive evidence for 8th-century social stratification, utilizing what Faust describes as "the largest archaeological data set in the world" for ancient Palestinian society.[31]

House size variations in cities like Samaria and Megiddo demonstrate dramatic differences in living standards between social classes. Elite residences feature multiple courtyards, decorated walls, and sophisticated water systems, while the majority of urban dwellings consist of simple two or three-room structures with minimal amenities. This architectural evidence confirms the prophetic descriptions of a society divided between a small wealthy elite and a large, impoverished majority.

The famous Samaria ivories provide particularly striking confirmation of prophetic critiques. These carved ivory plaques, discovered in the royal quarter, directly correspond to Amos 6:4's reference to "beds of ivory" used by the wealthy elite. The artistic sophistication and imported materials demonstrate the scale of elite consumption while validating the accuracy of prophetic observations about luxury and excess.[32]

Agricultural Intensification and Processing Systems

Archaeological evidence reveals massive expansion of agricultural infrastructure during the 8th century, including terracing systems, water management installations, and processing facilities that transformed the landscape and agricultural economy. Optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating confirms that terracing construction peaked during this period, indicating systematic investment in agricultural intensification.[33]

The scale of processing facilities provides crucial evidence for understanding the transformation from subsistence to commercial agriculture. Sites like Megiddo feature massive grain silos with storage capacity exceeding 450 cubic meters, while installations for olive oil and wine production reveal industrial-scale processing designed for export markets rather than local consumption.[34]

The LMLK (למלך, "belonging to the king") jar stamp system, with over 2,000 documented handles, demonstrates sophisticated administrative control over agricultural production and distribution. These stamps indicate royal estates managed through centralized bureaucracy, reflecting the land consolidation that prophets like Micah condemned in their critiques of elite property accumulation.[35]

Economic Transformation: From Kinship to Market Agriculture

Debt Mechanisms and Land Transfer

The transformation from traditional kinship-based agriculture to elite-controlled latifundia required legal mechanisms that enabled wealthy creditors to acquire peasant lands through debt foreclosure. Comparative evidence from other ancient Near Eastern societies reveals how debt instruments functioned to transfer property from small farmers to urban elites during economic transformation.[36]

Analysis of debt mechanisms reveals how creditors exploited traditional land tenure systems through foreclosure practices that were technically legal but fundamentally exploitative. The process typically began when peasant families required loans for survival during poor harvest years or to meet tax obligations. When families couldn't repay loans with traditional agricultural surplus, creditors could demand land as collateral, eventually acquiring entire estates through systematic foreclosure.[37]

The adoption procedures documented in ancient Near Eastern legal texts reveal another mechanism for property transfer. Wealthy creditors could use kinship fiction to acquire property by "adopting" indebted farmers, gaining legal rights to their land while maintaining the appearance of family relationships. These practices violated the spirit of covenant law while remaining technically within legal boundaries.

Archaeological evidence for this transformation appears in settlement patterns showing abandoned rural sites concurrent with expanded elite estates. The reduction in small farming settlements during the 8th century reflects the displacement of subsistence farmers who lost their land through debt mechanisms and were forced to seek survival in urban centers or as agricultural laborers on large estates.

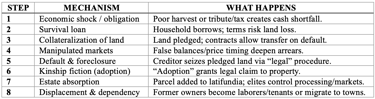

Table 3: Debt → Dispossession Process

Specialization and Export Agriculture

The shift from diversified subsistence farming to specialized cash crop production represents one of the most significant economic transformations of the 8th century. Archaeological evidence reveals massive expansion of viticulture and olive oil production designed for export markets rather than local consumption.[38]

Wine press installations increased dramatically during this period, concentrated in areas with favorable growing conditions but also requiring significant capital investment for processing equipment and storage facilities. This specialization made farmers vulnerable to market fluctuations and crop failures while increasing dependence on cash income for purchasing basic necessities that families had previously produced themselves.

Olive oil production became particularly important for international trade, with Israel emerging as a major supplier to both Egypt and Assyria. The industrial scale of processing facilities indicates production levels far exceeding local consumption needs, confirming the export orientation of agricultural development. However, this specialization came at the cost of food security as families abandoned traditional diversified farming that had provided protection against harvest failures.

The concentration of processing facilities on large estates demonstrates how agricultural intensification reinforced social stratification. Small farmers lacked the capital necessary for sophisticated processing equipment, making them dependent on estate owners for access to markets. This dependency enabled further exploitation through unfavorable processing agreements and marketing arrangements.

Prophetic Responses: Voices of Economic Critique

Amos: The Shepherd's Systematic Analysis

Amos's prophetic ministry during the height of Jeroboam II's prosperity provides the most systematic critique of 8th-century economic transformation. His background as a shepherd and farmer from Tekoa in Judah provided intimate knowledge of agricultural systems while maintaining outsider perspective on Northern Israel's commercial practices.[39]

The specificity of Amos's economic observations demonstrates detailed familiarity with exploitative mechanisms. His condemnation of those who "sell the righteous for silver and the needy for a pair of sandals" (2:6) addresses the process of making a binding agreement—the equivalent of a fingerprint as in Ruth 4:7 (viz., sandals that mold to fit a specific person's feet).[40]

Amos's critique of commercial dishonesty in 8:4-6 reveals sophisticated understanding of measurement manipulation, price fixing, and quality adulteration that characterized urban markets. The reference to "making the ephah small and the shekel great" describes manipulation of currency to exploit the timing of borrowing and repayment of loans ("false weights and measures"), while "mixing the sweepings with the wheat" addresses exploitation of the poor by selling refuse from the threshing process in the wheat sold to the poor. The prophet's condemnation of judicial corruption in 5:10-12 connects economic exploitation to institutional breakdown. The "gate" proceedings where disputes were traditionally resolved had become venues for systematic bribery, with wealthy defendants able to purchase favorable verdicts while the poor faced predetermined defeat. This corruption of traditional legal protections removed the final barriers to unlimited exploitation.

Hosea: Marriage Metaphor and Economic Betrayal

Hosea's prophetic ministry employed marriage metaphor to address the same economic conditions that Amos criticized directly, but with greater emphasis on covenant relationship and restoration possibilities. His personal experience of marital betrayal provided a framework for understanding Israel's infidelity through economic partnerships that violated covenant obligations.[41]

The marriage metaphor enabled Hosea to address economic injustice as relationship betrayal rather than merely legal violation. The image of Israel as an unfaithful wife who credits her prosperity to foreign lovers (2:5) directly addresses the attribution of economic success to Baal worship and Assyrian partnership rather than covenant faithfulness to YHWH.

Hosea's critique of commercial dishonesty in 12:7-8 employs the same marriage framework to address systematic exploitation. The reference to "false balances in the trader's hand" connects commercial fraud to covenant unfaithfulness, while the claim that "no one finds iniquity" addresses the elite's denial of obvious corruption through theological rationalization.

The prophet's emphasis on "knowledge of God" (4:1, 6:6) includes understanding of social justice obligations rather than merely cultic observance. This integration of theological knowledge with practical ethics establishes the foundation for understanding economic justice as essential to authentic covenant relationship rather than optional charitable activity.

Micah: Rural Voice Against Urban Exploitation

Micah's prophetic ministry represents the rural perspective on urban exploitation that characterized 8th-century economic transformation. His background in Moresheth, a small agricultural town southwest of Jerusalem, provided firsthand experience of the pressure that urban elites placed on rural communities through land acquisition and debt manipulation.[42]

The prophet's condemnation of systematic land seizure in 2:1-2 addresses the specific mechanisms documented by archaeological evidence. The phrases "covet fields and seize them" and "oppress a householder and his house" describe the debt foreclosure processes that transferred property from traditional farmers to urban investors, breaking the covenant principles of inalienable family inheritance.[43]

Micah's use of cannibalistic imagery to describe elite exploitation (3:2-3) reflects the severity of rural suffering caused by systematic property transfer. The metaphor of eating flesh and flaying skin communicates the complete destruction of traditional rural communities through land consolidation and agricultural transformation.

The prophet's vision of restoration in 4:4, where "everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree," presents an alternative economic model based on secure family tenure and diversified agriculture rather than large estate specialization. This vision challenges the inevitability of economic concentration while maintaining hope for covenant-based economic relationships.

Isaiah: Urban Prophet's Imperial Analysis

Isaiah's prophetic ministry addressed the same economic conditions from the perspective of Jerusalem's urban elite, providing insider knowledge of policy decisions and imperial relationships that shaped economic development. His aristocratic background and court connections enabled sophisticated analysis of the relationship between domestic economic policy and international political pressures.[44]

The prophet's condemnation of land consolidation in 5:8 employs legal language that reveals detailed understanding of property law and acquisition mechanisms. The phrase "join house to house, add field to field" describes the systematic accumulation of property through legal but exploitative means, while the prediction of agricultural failure addresses the environmental consequences of intensive monoculture.

Isaiah's critique of luxury consumption and judicial corruption in 5:11-12, 22-23 connects elite hedonism to systematic oppression of the poor. The description of those who "rise early to run after drinks" and "are heroes at mixing strong drink" addresses the moral corruption that accompanied economic success, while the condemnation of those who "acquit the guilty for a bribe" connects personal excess to institutional injustice.

The prophet's response to imperial pressure through his critique of foreign alliances (7:1-17, 30:1-5) addresses the economic implications of tribute obligations and military expenditures that required intensive surplus extraction from the peasant population. His advocacy for faith-based policy rather than political calculation challenged the assumption that economic survival required accommodation to imperial demands.

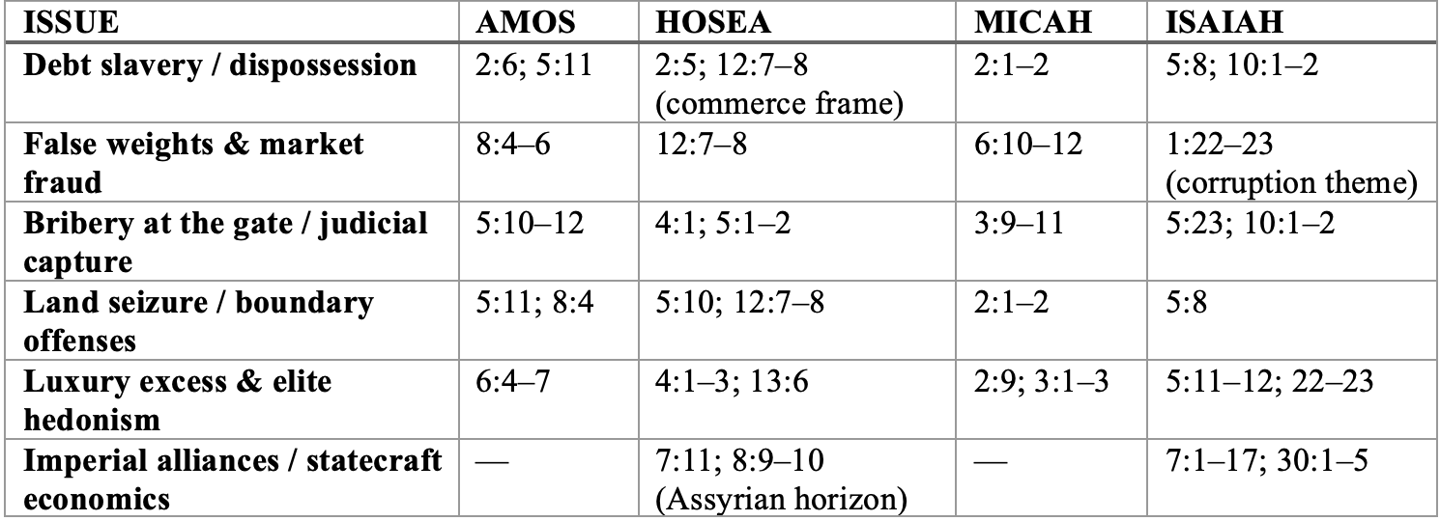

Table 4: 8th Century BCE Economic Issues Per Prophet.

Synthesis: The "Unholy Trio" of Money, Sex, and Power

Jerry Hwang's analysis reveals how 8th-century prophets address three interconnected forms of covenant violation through what he terms the "unholy trio" of money, sex, and power, demonstrating how economic exploitation, sexual violation, and political corruption functioned as mutually reinforcing problems rather than isolated moral failures.[45]

Economic exploitation provides foundational violations that enable other forms of covenant transgression. The loss of patrimonial lands due to debt foreclosure—often resulting from exploitative lending practices by urban elites—forced vulnerable families into desperate situations where sexual exploitation became survival strategies rather than freely chosen activities.[46]

Specific passages link sexual immorality, economic exploitation, and religious corruption, demonstrating how sexual exploitation became normalized within religious contexts that should have protected vulnerable populations.[47] Cultic prostitution represented more than religious apostasy—it functioned as economic institution that monetized sexual access while providing religious legitimization for practices that violated fundamental standards for human dignity.[48]

The political dimensions focus on how corruption of judicial systems and political institutions enabled and legitimized both economic exploitation and sexual violation through systematic perversion of legal processes that should have protected vulnerable populations but instead became instruments for legitimizing harmful practices.[49]

Sophisticated literary analysis shows how references to fertility religion functioned simultaneously as literal descriptions of religious practices and metaphorical representations of "relentless materialism" and "economic growth at all costs."[50] Baal worship provided ideological justification for economic arrangements that prioritized surplus extraction and elite luxury over communal welfare and environmental sustainability.[51]

Recent algorithmic analysis of the Samaria ostraca has revealed that only two scribes produced thirty-one of the more than one hundred ostraca, indicating highly centralized palace bureaucracy rather than widespread literacy. This transforms understanding of administrative systems in the Northern Kingdom while providing context for critique of centralized power structures that enabled elite control over agricultural production.[52]

Comparative Analysis: North and South

Structural Similarities and Different Outcomes

Both Israel and Judah experienced remarkably similar patterns of agricultural intensification, social stratification, and prophetic response during the 8th century, yet their divergent political trajectories profoundly influenced how prophetic literature was preserved and interpreted.[53]

The eighth century marked unprecedented economic development throughout the Levantine corridor. Archaeological evidence demonstrates that both kingdoms underwent systematic transformation from subsistence agriculture to specialized commercial production. Pottery analysis reveals standardized production techniques and vessel forms, indicating increased centralization and state control over economic activities.[54]

Both kingdoms developed export-oriented agricultural economies that fundamentally altered traditional farming practices. Wine press installations proliferated across suitable terrain, while olive oil processing facilities reached industrial scales far exceeding local consumption needs. This specialization created wealth but also vulnerability, as families abandoned diversified subsistence farming that had provided security against harvest failures.[55]

Archaeological evidence reveals virtually identical social stratification in both kingdoms. Eighth-century urban sites consistently display only two distinct socioeconomic classes: a small wealthy elite comprising approximately two percent of the population, and a large majority living in significantly reduced circumstances.[56]

Impact of Northern Refugees

The demographic absorption of northern refugees after 722 BCE fundamentally transformed Judah's social and cultural development while ensuring the preservation of northern prophetic traditions. Archaeological evidence suggests that Jerusalem's population may have increased by 53% following the Assyrian conquest, with entire neighborhoods established for displaced northerners.[57]

Northern refugees brought sophisticated administrative expertise and literary traditions that enhanced Judah's institutional capacity. Many displaced persons were educated elites, including scribes, government officials, and craftsmen, who integrated into Judah's expanding bureaucracy.[58]

The preservation of northern prophetic literature within southern scribal traditions represents one of the most significant cultural achievements of this refugee integration. Northern voices like Amos and Hosea found new audiences through southern editorial work that adapted their messages for Judean contexts while preserving their essential critiques of social and economic injustice.[59]

Political Stability and Survival Strategies

Judah's political continuity under the Davidic dynasty provided crucial advantages for managing the economic and political pressures that destroyed the northern kingdom. Unlike Israel, which experienced frequent dynastic changes and civil conflicts, Judah maintained stable governance for over four centuries.[60]

The kingdom's defensive geography offered additional protection that northern Israel lacked. Judah's mountainous terrain provided natural barriers against military invasion, while its location south of major international trade routes initially made it less attractive to imperial powers.[61]

Cultural and religious traditions centered on Jerusalem and the Davidic covenant provided ideological cohesion that helped Judah maintain unity during external pressure.[62]

Regional Variations in Prophetic Response

The distinctive emphases among 8th-century prophets reflect their specific social locations and target audiences while addressing identical economic transformation processes.[63]

Rural Perspectives: Amos and Micah

Amos and Micah, representing rural agricultural backgrounds, concentrated primarily on land tenure violations and subsistence agriculture destruction. Amos, described as "a herdsman and a dresser of sycamore trees," brought firsthand experience of traditional pastoral and agricultural systems to his critique of commercial expansion.[64]

Archaeological evidence validates these rural concerns through documentation of widespread land consolidation and estate development. Settlement pattern analysis reveals abandoned small farming sites concurrent with expanded processing facilities on large estates.[65] The material record shows precisely what the rural prophets described: traditional family farms disappearing as wine press installations and olive processing facilities concentrated on large estates requiring capital investment beyond peasant capacity.

Micah's prophetic ministry from the Judean countryside provided parallel analysis of latifundialization processes that displaced rural families from ancestral holdings.[66] The rural prophetic perspective emphasized covenant violations inherent in land tenure transformation. Traditional clan-based inheritance systems were systematically undermined by debt instruments and foreclosure practices that treated land as commodity rather than inalienable family heritage.[67]

Both prophets understood intimately how agricultural intensification destroyed rural security. The shift from diversified subsistence farming to specialized cash crop production made peasant families vulnerable to market fluctuations, harvest failures, and price manipulation by urban merchants who controlled processing facilities and trade networks. Their critiques reveal detailed knowledge of how economic transformation operated at ground level—the actual mechanisms by which farmers lost ancestral lands and became dependent laborers.

Urban Perspectives: Hosea and Isaiah

Hosea and Isaiah, with greater access to urban commercial and political networks, addressed international relationships and commercial practices more extensively than their rural counterparts.[68] Their urban vantage points enabled analysis of how local exploitation connected to broader imperial economic systems.

The complexity of Hosea's imagery suggests familiarity with urban commercial practices and diplomatic negotiations. His condemnation of "false balances" and commercial dishonesty (Hosea 12:7-8) reveals detailed knowledge of market manipulation techniques—the specific methods merchants used to defraud customers through measurement fraud and price timing. His critique of foreign alliances demonstrates understanding of how international relationships affected domestic economic policy, particularly how tribute obligations to Assyria drove the intensive surplus extraction that required land consolidation and agricultural transformation.[69]

Isaiah's prophetic ministry was deeply embedded in Jerusalem's political and commercial life, providing direct access to royal court deliberations and international diplomatic developments.[70] His oracles reveal insider knowledge of policy debates regarding Egyptian versus Assyrian alliances, military expenditure decisions, and administrative reorganization that facilitated surplus extraction. Isaiah understood how elite consumption patterns required systematic exploitation—the luxury goods, monumental construction projects, and military apparatus that urban elites enjoyed necessitated the rural dispossession that Amos and Micah witnessed firsthand.[71]

Isaiah's critique of judicial corruption (5:23) and his condemnation of those who "acquit the guilty for a bribe" reflects understanding of how urban legal institutions had become instruments of exploitation rather than protection. The gate proceedings where disputes were adjudicated had been captured by wealthy interests, systematically ruling against peasant debtors to facilitate property transfer to elite creditors.

Complementary Analytical Approaches

These regional variations demonstrate the comprehensive nature of economic transformation affecting all societal levels while requiring diverse analytical approaches for full understanding.[72] The preservation of multiple prophetic voices enables contemporary readers to understand the complexity of 8th-century conditions while appreciating different methodological approaches to analyzing systematic injustice.[73]

This diversity also demonstrates the analytical sophistication of prophetic social criticism. Eighth-century prophets were not merely moral critics but demonstrated detailed understanding of economic processes, political relationships, and social structures.[74] The canonical preservation of these diverse perspectives suggests that later editors recognized the value of multiple analytical approaches for understanding complex social and economic transformations.[75]

Conclusion: Enduring Relevance of Prophetic Witness

The 8th-century prophets emerged during Israel's most prosperous era precisely because material success had created conditions that violated covenant principles of economic justice and social solidarity. Their systematic critique of debt mechanisms, land consolidation, and judicial corruption addressed specific historical conditions while establishing theological principles that transcend temporal boundaries.

Archaeological evidence confirms the accuracy of prophetic social analysis while revealing the sophistication of their economic understanding. These were not naive religious reformers but careful observers of political economy who recognized how material conditions affected spiritual authenticity and community relationships.

The integration of prosperity and injustice that characterized 8th-century Israel and Judah represents patterns that remain remarkably contemporary. The mechanisms of systematic exploitation, the corruption of legal institutions, and the rationalization of disparities through religious ideology continue to challenge communities seeking to embody justice and righteousness.

The prophetic legacy offers both critique and hope for contemporary contexts. Their systematic analysis of economic injustice provides tools for understanding how prosperity can create conditions that undermine the values it supposedly represents. Their theological vision maintains hope for transformation through divine initiative and human response, establishing foundations for continued witness to justice and righteousness in every generation.

The enduring significance of 8th-century prophetic literature lies not in its historical interest but in its continuing capacity to illuminate the relationship between material conditions and spiritual authenticity. These ancient voices speak to contemporary challenges with remarkable clarity, offering both analytical tools and theological hope for communities committed to economic justice and social transformation.

Discussion Questions

1. The Methodology Question: How does the integration of archaeological evidence with biblical texts change our understanding of prophetic literature? What tensions arise when material culture confirms some prophetic claims while remaining silent on others?

2. The Regional Variation Question: The article shows that Amos and Micah (rural backgrounds) emphasized land tenure violations while Hosea and Isaiah (urban contexts) focused more on commercial practices and international relations. What does this diversity of perspective reveal about the comprehensiveness of 8th-century economic transformation? Would we understand the crisis adequately with only one prophetic voice?

3. The Theological-Economic Integration Question: The prophets connected covenant faithfulness directly to economic practices—not as separate spheres but as fundamentally integrated. How did this differ from typical ancient Near Eastern religious approaches? What made the Israelite prophetic tradition unique in linking theology so explicitly to political economy?

4. The Legal Exploitation Question: The article demonstrates how 8th-century elites used technically legal mechanisms (debt instruments, adoption procedures, judicial processes) to violate covenant principles. How did the prophets distinguish between legal legitimacy and covenantal justice? What does this reveal about the limitations of legal systems in preventing systematic exploitation?

5. The Preservation Question: Why did southern Judean scribes preserve northern prophetic literature after 722 BCE, especially critiques that could apply equally to Judah's own economic practices? What does the canonical preservation of multiple critical voices suggest about how later communities understood prophetic witness and its ongoing relevance?

Endnotes

[1] Avraham Faust, The Archaeology of Israelite Society in Iron Age II (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2012), 45-78; Israel Finkelstein, The Forgotten Kingdom: The Archaeology and History of Northern Israel (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013), 123-156.

[2] Marvin L. Chaney, "Peasants, Prophets, and Political Economy in Ancient Israel," in The Hebrew Bible in Its Social World and in Ours (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 2017), 289-324.

[3] Wayne T. Pitard, Ancient Damascus: A Historical Study of the Syrian City-State from Earliest Times until Its Fall to the Assyrians in 732 BCE (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1987), 145-167.

[4] Amnon Ben-Tor, ed., The Archaeology of Ancient Israel (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 302-317.

[5] Hayim Tadmor, The Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III King of Assyria (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1994), 78-92.

[6] Andre Lemaire, Inscriptions hébraïques: Tome I, Les ostraca (Paris: Cerf, 1977), 23-45.

[7] Marvin L. Chaney, "Peasants, Prophets, and Political Economy in Ancient Israel," 289-324.

[8] Gerhard Lenski, Power and Privilege: A Theory of Social Stratification (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966), 89-112.

[9] Lenski, Power and Privilege, 134-156.

[10] Chaney, "Debt Easement in Israelite History and Tradition," in The Bible and the Politics of Exegesis, ed. David Jobling, Peggy L. Day, and Gerald T. Sheppard (Cleveland: Pilgrim Press, 1991), 127-139.

[11] William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001), 98-156.

[12] Faust, Archaeology of Israelite Society, 23-44.

[13] Faust, Archaeology of Israelite Society, 67-89.

[14] Carol Meyers, Discovering Eve: Ancient Israelite Women in Context (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 123-145.

[15] Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know, 234-267.

[16] Francis I. Andersen and David Noel Freedman, Hosea, Anchor Bible 24 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1980), 587-612.

[17] Shalom M. Paul, Amos, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1991), 78-85.

[18] Andersen and Freedman, Hosea, 223-245.

[19] Christopher J.H. Wright, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2004), 167-189.

[20] John H. Walton, The NIV Application Commentary: Leviticus (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009), 445-467.

[21] Walter Brueggemann, 1 & 2 Kings, Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary (Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys, 2000), 256-278.

[22] J. Gordon McConville, Deuteronomy, Apollos Old Testament Commentary (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2002), 312-334.

[23] Hans Walter Wolff, Micah, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1990), 67-84.

[24] Peter C. Craigie, The Book of Deuteronomy, New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1976), 345-378.

[25] Andersen and Freedman, Hosea, 527-543.

[26] John D.W. Watts, Isaiah 1-33, Word Biblical Commentary 24 (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1985), 63-89.

[27] Gerhard F. Hasel, The Remnant: The History and Theology of the Remnant Idea from Genesis to Isaiah, 3rd ed. (Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press, 1980), 234-267.

[28] Bruce C. Birch, Hosea, Joel, and Amos, Westminster Bible Companion (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1997), 178-201.

[29] Magen Broshi and Israel Finkelstein, "The Population of Palestine in Iron Age II," Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 287 (1992): 47-60.

[30] Faust, Archaeology of Israelite Society, 156-189.

[31] Faust, Archaeology of Israelite Society, 67.

[32] John W. Crowfoot and Grace M. Crowfoot, Early Ivories from Samaria (London: Palestine Exploration Fund, 1938), 12-34.

[33] Amos Frumkin et al., "OSL Dating of Agricultural Terraces in the Judean Highlands," Journal of Archaeological Science 38 (2011): 2636-2642.

[34] Israel Finkelstein, David Ussishkin, and Baruch Halpern, eds., Megiddo IV: The 1998-2002 Seasons (Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, 2006), 234-267.

[35] David Ussishkin, "The LMLK Stamped Jar Handles," Tel Aviv 4 (1977): 28-58.

[36] Michael Hudson, ed., Forgive Them Their Debts: Lending, Foreclosure and Redemption from Bronze Age Finance to the Jubilee Year (Dresden: ISLET-Verlag, 2018), 145-178.

[37] Chaney, "Peasants, Prophets, and Political Economy," 295-302.

[38] David C. Hopkins, The Highlands of Canaan: Agricultural Life in the Early Iron Age (Sheffield: Almond Press, 1985), 234-256.

[39] Hans Walter Wolff, Joel and Amos, Hermeneia (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1977), 90-113.

[40] Paul, Amos, 78-85.

[41] Andersen and Freedman, Hosea, 45-67.

[42] Wolff, Micah, 23-39.

[43] Wolff, Micah, 67-84.

[44] Watts, Isaiah 1-33, 34-56.

[45] Jerry Hwang, "The Unholy Trio of Money, Sex, and Power in Israel's 8th-Century BCE Prophets," Jian Dao 41 (2014): 183-190.

[46] Hwang, "Unholy Trio," 195-200.

[47] Hwang, "Unholy Trio," 203-207.

[48] D.N. Premnath, Eighth Century Prophets: A Social Analysis (St. Louis: Chalice Press, 2003), 167-189.

[49] Hwang, "Unholy Trio," 183-185.

[50] Hwang, "Unholy Trio," 194-198.

[51] Walter Wink, The Powers That Be: Theology for a New Millennium (New York: Doubleday, 1998), 67-89.

[52] Arie Shaus et al., "Algorithmic Handwriting Analysis of the Samaria Inscriptions Illuminates Bureaucratic Apparatus in Biblical Israel," PLOS ONE 15, no. 1 (2020): e0227223.

[53] Faust, Archaeology of Israelite Society, 189-234.

[54] Finkelstein, The Forgotten Kingdom, 89-112.

[55] Hopkins, The Highlands of Canaan, 178-201.

[56] Faust, Archaeology of Israelite Society, 234-267.

[57] Oded Lipschits, The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: Judah under Babylonian Rule (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2005), 123-145.

[58] Lipschits, The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem, 167-189.

[59] Marvin A. Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2005), 78-102.

[60] Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know, 134-156.

[61] Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know, 178-201.

[62] Jon D. Levenson, Sinai and Zion: An Entry into the Jewish Bible (Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1985), 89-112.

[63] Chaney, "Peasants, Prophets, and Political Economy," 310-318.

[64] Wolff, Joel and Amos, 90-113.

[65] Hopkins, The Highlands of Canaan, 234-256.

[66] Wolff, Micah, 67-84.

[67] Norman K. Gottwald, The Tribes of Yahweh: A Sociology of the Religion of Liberated Israel (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1979), 234-267.

[68] Andersen and Freedman, Hosea, 45-67.

[69] Andersen and Freedman, Hosea, 89-112.

[70] Watts, Isaiah 1-33, 34-56.

[71] Watts, Isaiah 1-33, 78-102.

[72] Chaney, "Peasants, Prophets, and Political Economy," 310-318.

[73] Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 123-145.

[74] Gottwald, The Tribes of Yahweh, 289-324.

[75] Sweeney, The Prophetic Literature, 167-189.