When Your Enemy Saves Your Life: The Good Samaritan's Radical Reversal (Luke 10:30-35)

The Good Samaritan parable traps listeners into uncomfortable victim-identification, challenging them to receive mercy from their despised enemy rather than simply offering charity to the safely marginalized. Jesus redefines neighbor-love as "love from below"—relating from vulnerable need rather than patronizing power—forcing the lawyer to acknowledge he must be served by a Samaritan, stripped of all pretense and pride. Through sophisticated literary structure and connections to 2 Chronicles 28, the parable reveals divine compassion operating through unexpected sources while challenging exclusivist definitions of covenant membership within Luke's Israel-restoration theology, ultimately transforming comfortable moral instruction into devastating critique of religious superiority.

Greg Camp and Patrick Spencer

10/19/202534 min read

NOTE: This article was researched and written with the assistance of AI.

Top Takeaways

The Samaritan Was the Enemy, Not Just a Helpful Stranger. First-century Jews considered Samaritans worse than ordinary gentiles—not ignorant outsiders but deliberate apostates who corrupted true worship while claiming authentic Israelite heritage. Jesus deliberately chose the most offensive possible hero to force his audience into unbearable recognition: their despised enemy proved more faithful to covenant law than Jerusalem's religious professionals.

The Parable Functions as Rhetorical Trap, Not Moral Example. Jesus reversed the lawyer's self-justifying question ("Who is my neighbor?") into an indictment ("Who proved to be neighbor?"), forcing him to acknowledge the Samaritan's superiority while being unable to even say the word "Samaritan." The lawyer came seeking boundaries to limit moral obligation but left trapped in his own prejudices, compelled to recognize that mercy-showing transcends all ethnic and religious categories he wanted to maintain.

Compassion Is Divine Participation, Not Human Sentiment. Luke reserves the visceral compassion verb (σπλαγχνίζομαι) for only three moments—Jesus healing the widow's son, the father embracing the prodigal, and the Samaritan helping the victim—creating a "compassion cluster" linking human action with divine character. The Samaritan embodies the same gut-wrenching, action-producing divine mercy that Luke attributes to Jesus and God the Father, suggesting authentic neighbor-love represents participation in God's nature rather than mere ethical behavior.

The Parable Challenges Who Belongs to God's People, Not Just How to Treat Outsiders. Rather than universalizing love to all humanity, Jesus uses the parable within Luke's restoration theology to challenge narrow definitions of Israel that excluded Samaritans based on worship location. The primary issue is ecclesiological—who constitutes God's covenant community—demonstrated by how Luke presents Samaritans throughout Acts as part of Israel's reunification (Judea and Samaria) before gentile mission begins, not as foreigners being incorporated.

True Love Operates "From Below"—From Recognized Vulnerability, Not Patronizing Power. The parable redefines love itself by forcing the lawyer to identify with the beaten victim who must receive mercy from his enemy, not just with the benefactor deciding who deserves help. Barbarick's "love from below" framework reveals that Jesus challenges the lawyer to maintain the victim's posture of vulnerable openness even when offering aid, integrating both receiving unexpected mercy and extending compassion from awareness of one's own need rather than from condescending superiority.

The parable lodges in cultural memory as feel-good charity lesson: help strangers in need. Sunday school classes transform it into bland humanitarianism, corporate diversity training programs invoke it for team-building exercises, and political speeches deploy it as vague gesture toward civic virtue. This domestication obscures the story's original function as rhetorical trap designed to force first-century Jewish audiences into unbearable acknowledgment: those they considered religiously contaminated enemies might prove more faithful to covenant law than Jerusalem's religious professionals.

Literary structure and first-century social realities reveal something far more disturbing than generic altruism. Luke crafts the episode as carefully constructed assault on ethnic pride, religious institutionalism, and comfortable assumptions about moral identity. The narrative operates simultaneously as sophisticated literature, devastating social critique, and participatory rhetoric requiring active reader engagement rather than passive moral absorption. Understanding how the story works—its architecture, historical context, and rhetorical strategy—transforms comfortable charity tale into confrontation with questions about power, prejudice, and the sources of genuine mercy.

Road to Jericho: Geography and Narrative Frame

Descent into Danger

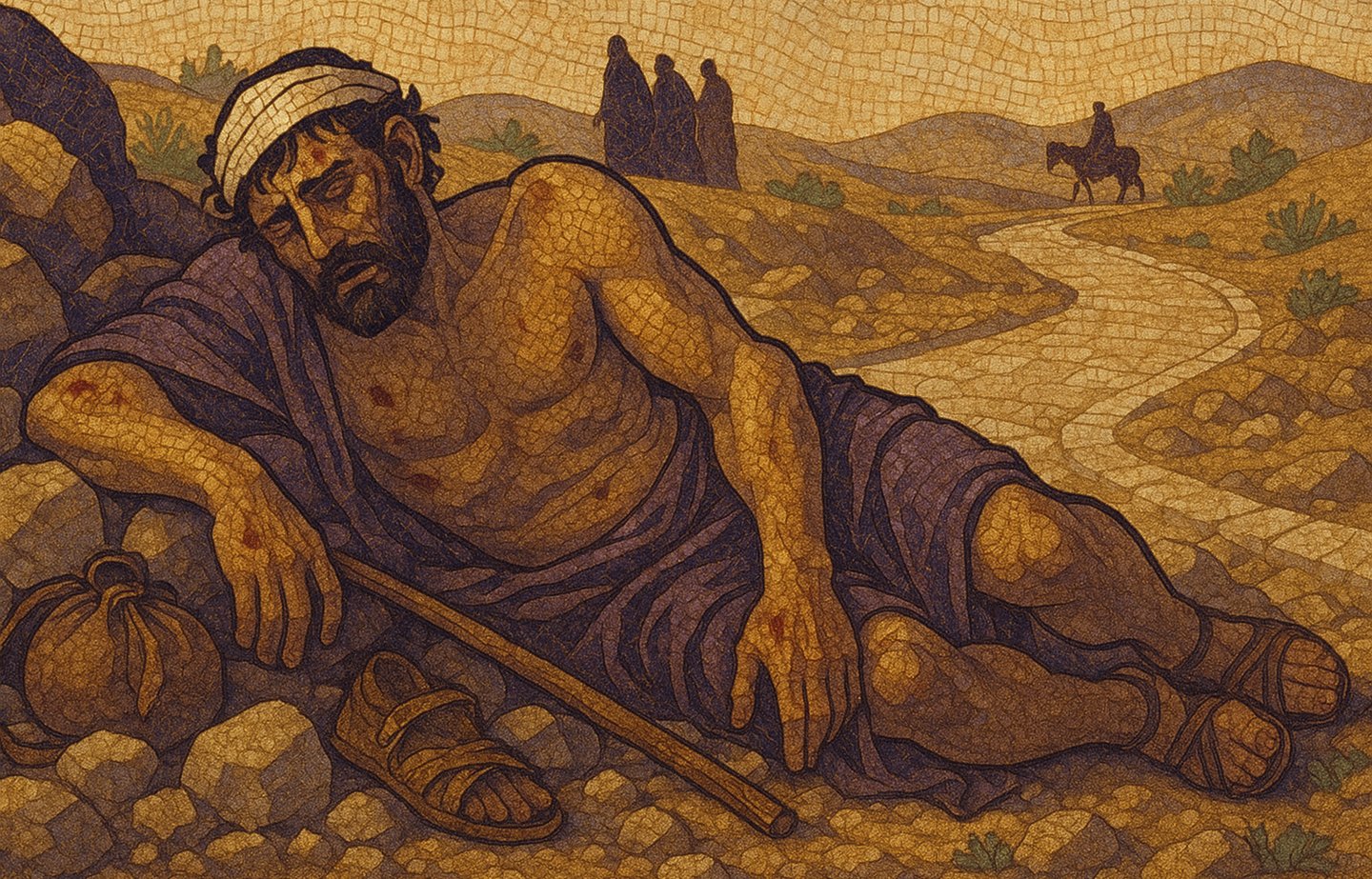

The seventeen-mile road from Jerusalem to Jericho drops nearly 3,300 feet through wilderness terrain that first-century audiences knew as notorious for bandit activity.[1] This geographical detail functions as more than atmospheric backdrop. Jerusalem represented sacred center—temple worship, priesthood, religious authority. Jericho signified the profane, a border town associated with Herod's opulent winter palace and morally compromising proximity to gentile territories.[2] Movement from Jerusalem downward toward Jericho carries symbolic weight: departure from holiness toward increasingly ambiguous moral territory.

Luke emphasizes this descent (καταβαίνω—going down) deliberately. The dangerous road provided perfect narrative setting for testing character under pressure. Travelers faced real risk of violence from bandits (ληστής—often translated 'robbers' but carrying connotations of violent brigands) who controlled wilderness areas beyond effective Roman jurisdiction.[3] The victim's condition—stripped, beaten, left ἡμιθανής (half-dead, a compound word appearing only here in the New Testament)—creates maximum vulnerability requiring immediate intervention without possibility of reciprocal reward or social recognition.

Lawyer's Trap That Becomes His Prison

Luke frames the parable within dialogue between Jesus and legal expert (νομικός—an expert in Torah law) seeking to 'test' him about eternal life requirements (10:25).[4] The lawyer answers his own question correctly by citing Deuteronomy 6:5 and Leviticus 19:18—comprehensive love of God and neighbor. Jesus affirms this response: "Do this and you will live" (10:28). End of discussion.

Except the lawyer 'wanting to justify himself' (θέλων δικαιῶσαι ἑαυτόν—the verb δικαιόω means to declare or prove righteous, to establish one's righteousness) presses forward with apparently innocent clarification: "Who is my neighbor?" (10:29).[5] This self-justifying question reveals the interpretive game. Leviticus 19:18 in its original context addressed behavior toward fellow Israelites—"your people," "sons of your people."[6] First-century Jewish interpretation debated whether 'neighbor' (πλησίον in Greek, translating Hebrew רֵעַ) extended beyond ethnic boundaries to include gentiles, but Samaritans occupied special category: not foreigners but apostates, not ignorant outsiders but deliberate rebels against true worship.

The lawyer's question seeks permission to draw boundaries excluding certain people from moral obligation. Jesus responds not with direct answer but with story forcing the questioner to draw his own conclusions—conclusions that will trap him in his own prejudices while simultaneously exposing them.

Blood Feud: Jewish-Samaritan Relations

Historical Origins of Mutual Contempt

The hostility between Jews and Samaritans stretched back centuries, rooted in theological dispute, ethnic prejudice, and political violence. After the Assyrian conquest of the Northern Kingdom in 722 BCE, foreign populations settled in Samaria and intermarried with remaining Israelites.[7] From the southern Jewish perspective, this created religiously compromised population lacking pure Israelite lineage and adhering to corrupted worship practices.

Samaritans accepted only the Pentateuch as scripture, rejecting prophetic and wisdom literature that Jews considered authoritative.[8] More provocatively, they worshiped at Mount Gerizim rather than Jerusalem's temple, claiming their site represented authentic tradition going back to Moses. This competing worship center struck at the heart of Jewish religious identity centered on Jerusalem and Davidic covenant.

The Hasmonean ruler John Hyrcanus destroyed the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim around 110 BCE, an act of religious violence that Samaritans remembered with bitter resentment.[9] First-century Jewish sources reveal the depth of contempt. Josephus describes Samaritans as claiming Jewish identity when convenient but distancing themselves during persecution—opportunists lacking genuine covenant loyalty.[10] Rabbinic tradition declared Samaritan testimony invalid in Jewish courts and their conversion to Judaism nearly impossible due to theological contamination passed through generations.

First-Century Realities: Worse Than Gentiles

The phrase "Jews do not associate with Samaritans" (John 4:9) captures social reality of rigid boundary maintenance.[11] But Samaritans occupied worse category than ordinary gentiles. Gentiles were ignorant outsiders who might eventually come to true faith. Samaritans were apostates who knew better but chose wrong worship, making them active rebels rather than passive unbelievers.

Recent scholarship challenges older assumptions about complete separation, revealing more nuanced and sometimes overlapping boundaries between communities.[12] Archaeological evidence shows some commercial interaction, and Josephus's accounts reveal occasional Samaritan-Jewish cooperation against common enemies. But these practical accommodations did not eliminate fundamental religious antagonism. Samaritans represented theological threat precisely because they claimed Israelite heritage while rejecting Jerusalem-centered worship—making them dangerous competitors rather than simple outsiders.

The conflict remained "intramural" within Israel's family rather than external ethnic warfare.[13] This sibling rivalry character intensified the hostility. Families often reserve their bitterest conflicts for those closest to them who betray shared heritage. Samaritans were not foreign enemies but traitorous relatives, not ignorant pagans but deliberate apostates who corrupted true worship while claiming authentic tradition. The question of whether this hostility obscures Samaritans' actual status as part of biblical Israel—and what that means for interpreting the parable—receives comprehensive treatment below in the section "Ecclesiological Dimensions: Who Belongs to Israel?"

Narrative Setup in Luke's Gospel

Luke's larger narrative arc prepares readers for the Good Samaritan's shocking appearance. In Luke 9:51-56, a Samaritan village refuses Jesus hospitality because he was heading toward Jerusalem for pilgrimage.[14] This rejection stems directly from the worship dispute—Samaritans viewed Jerusalem pilgrimage as implicit repudiation of Mount Gerizim's legitimacy.

James and John's response reveals typical Jewish hostility: "Lord, do you want us to command fire to come down from heaven and consume them?" (9:54). This violent impulse connects to Elijah's confrontation with Ahaziah's messengers in 2 Kings 1, where the prophet called down fire on those opposing him.[15] The disciples imagine themselves as Elijah's successors defending divine honor against rebellious Samaritans.

Jesus rebukes them, and the narrative moves forward. Jeremy Otten's analysis reveals sophisticated pattern: Jesus demonstrates true Elijah-like compassion by refusing violence against those who reject his mission.[16] The climax of the Elijah narrative was not judgment but the prophet's eventual descent to show mercy to the third captain who approached humbly (2 Kings 1:15). Jesus fulfills authentic prophetic tradition through restraint rather than revenge.

This sets up the Good Samaritan parable. After establishing Samaritan hostility and Jewish disciples' violent response, Luke presents Samaritan showing exemplary covenant faithfulness. The narrative progression creates cognitive dissonance requiring readers to reassess assumptions about who embodies true Israelite behavior and who betrays covenant obligations.

Narrative Architecture: How the Story Works

Seven-Part Chiastic Structure

The parable demonstrates sophisticated literary craftsmanship through seven-part chiastic structure that creates symmetrical parallels while emphasizing the Samaritan's compassion as central pivot point:[17]

A. Robbers attack and steal (v. 30a) "A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell into the hands of robbers, who stripped him, beat him, and went away, leaving him half dead"

B. Priest sees and passes by (v. 31) "Now by chance a priest was going down that road; and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side"

C. Levite sees and passes by (v. 32) "So likewise a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side"

D. CENTRAL PIVOT: Samaritan sees and shows compassion (v. 33) "But a Samaritan while traveling came near him; and when he saw him, he was moved with compassion"

C'. Samaritan bandages wounds (v. 34a) "He went to him and bandaged his wounds, having poured oil and wine on them"

B'. Samaritan transports to safety (v. 34b) "Then he put him on his own animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him"

A'. Samaritan pays and provides (v. 35) "The next day he took out two denarii, gave them to the innkeeper, and said, 'Take care of him; and when I come back, I will repay you whatever more you spend'"

This structure creates systematic reversals between the robbers' actions and the Samaritan's response. Where robbers stripped, the Samaritan provided clothing through wine and oil treatment. Where robbers beat, the Samaritan bound wounds. Where robbers took the victim's money, the Samaritan spent his own resources. Where robbers left the victim isolated, the Samaritan ensured ongoing community care.[18]

The chiastic pattern focuses attention on the central moment: the Samaritan's visceral compassion. This structural emphasis will prove significant when examining the parable's intertextual connections and theological implications.

Character Analysis: Escalating Expectation and Shocking Reversal

The parable's character sequence builds narrative tension through frustrated expectations. First-century Jewish audiences would anticipate three-part progression moving from religious professionals toward eventual hero—perhaps a pious layperson who demonstrates true covenant faithfulness despite lacking institutional credentials.[19]

The Victim enters stripped of all social markers. No name, occupation, tribal affiliation, or distinctive features remain after the robbers finish. This anonymity prevents audience from prejudging whether he deserves help based on social categories. The description "half-dead" creates maximum urgency—life hangs in balance, demanding immediate response without time for calculation or consultation.[20]

The Priest appears first, highest in religious hierarchy. Priests mediated between God and people through temple sacrifice, making them paradigmatic representatives of covenant relationship. The text emphasizes he "saw him" before passing by, eliminating ignorance as explanation for inaction.[21] The priest actively chooses avoidance, crossing to the opposite side of the road to maximize distance from the wounded man.

The Levite follows identical pattern with crucial intensification: he "came to the place and saw him," suggesting closer inspection before similarly passing by.[22] Levites assisted priests in temple service, ranking second in religious hierarchy. The repetitive structure creates pattern suggesting institutional religion systematically fails to embody covenant obligations. Two representatives of religious establishment both see human need and choose inaction.

Audience expectation builds toward third character providing successful contrast. Three-part sequence was standard rhetorical pattern in ancient storytelling. Listeners would anticipate pious Israelite layperson—perhaps poor farmer or craftsman—demonstrating that authentic faith transcends institutional position.[23]

The Samaritan obliterates these expectations. Luke introduces him with stark contrast particle: "But a Samaritan while traveling." The ethnic designation appears emphatic and shocking. Not just "another traveler" but specifically "a Samaritan"—forcing audience to process the unthinkable proposition that their despised enemy might prove more faithful to covenant law than Jerusalem's religious professionals.[24]

Compassion Verb: Emotional Intelligence and Divine Nature

The description of the Samaritan's response deserves careful attention: 'when he saw him, he was moved with compassion.' This verb (σπλαγχνίζομαι) derives from σπλάγχνα (internal organs)—guts, bowels, the seat of emotional response in ancient physiology.[25] Modern translation "compassion" sanitizes the visceral, gut-wrenching quality of the original. The Samaritan experiences physical, involuntary response to another's suffering.

Patrick Spencer's analysis applies emotional intelligence framework to Lukan characterization, revealing how this moment demonstrates all four components of emotional competency. The Samaritan exhibits self-awareness by recognizing his emotional response rather than suppressing it, self-management by channeling emotion into constructive action rather than being overwhelmed, social awareness by accurately perceiving the victim's desperate need across ethnic boundaries, and relationship management through effective engagement with both victim and innkeeper to ensure ongoing care.[26]

Ancient philosophical discourse debated appropriate emotional response to suffering. Strict Stoic tradition advocated eliminating all emotion as irrational disturbance preventing virtue.[27] But alternative Aristotelian and Plutarchian traditions recognized that properly calibrated emotional response to genuine suffering represented virtue rather than weakness. The Samaritan exhibits this ideal: experiencing appropriate emotional response, choosing to engage rather than suppress it, and converting emotion into rational action without losing control.[28]

Luke reserves this particular compassion verb for only three moments in his Gospel—describing Jesus healing the widow of Nain's son (7:13), the father embracing the prodigal son (15:20), and here with the Good Samaritan (10:33).[29] The pattern of "compassion leading immediately to action" appears consistently: when Jesus feels compassion for the widow, he immediately raises her son (7:13-15); when the prodigal's father feels compassion, he immediately runs to embrace and restore his son (15:20-24); the Samaritan's compassion in verse 33 produces immediate, comprehensive response in verses 34-35.[30]

This linguistic pattern suggests showing compassion represents participation in divine nature rather than mere human sentiment. The "compassion cluster" creates theological link between Jesus, God the Father, and the Good Samaritan. The Samaritan becomes human incarnation of divine mercy within the narrative world, embodying the same compassionate divine nature that Luke attributes to Jesus and to God.[31]

Reading Against 2 Chronicles 28: The Intertextual Dimension

Structural Parallels with Israel's Dark History

F. Scott Spencer's detailed analysis reveals extensive connections between the Good Samaritan parable and 2 Chronicles 28:5-15, suggesting Jesus deliberately draws on this obscure historical narrative to challenge audience prejudices.[32] The Chronicles passage describes how northern Israelites (later identified with Samaritans) showed mercy to Judean captives at the prophet Oded's urging—a story first-century Jewish audiences would know but perhaps prefer to forget.

The structural parallels with the parable's seven-part chiastic structure (presented above) are striking. The Israelites "clothed all who were naked among them; they clothed them, gave them sandals, provided them with food and drink, and anointed them; and carrying all the feeble among them on donkeys, they brought them to their kindred at Jericho" (2 Chronicles 28:15).[33] The vocabulary of stripping/clothing, anointing with oil, placing on animals, and bringing to Jericho creates unmistakable connection.

Hermeneutical Challenge: Scripture Interpreting Scripture

Jesus employs sophisticated hermeneutical strategy. He uses one biblical narrative to illuminate proper interpretation of biblical law. Leviticus 19:18 commands "love your neighbor as yourself," but who counts as neighbor remained contested. By invoking 2 Chronicles 28, Jesus demonstrates that even during Judah's apostasy under King Ahaz, northern Israelites (Samaritan ancestors) understood covenant obligation to show mercy across political and religious divisions.[34]

The historical context intensifies the challenge. Second Chronicles 28 describes Judah at its worst—King Ahaz closing the temple, practicing child sacrifice, and importing foreign worship (28:2-4, 24-25). Yet the text presents Israelites from the north responding to prophetic call for mercy toward their enemies. The implied argument cuts deep: if Samaritans' ancestors showed covenant faithfulness during Israel's darkest period, what excuse do contemporary priests and Levites have for failing basic mercy obligations?[35]

Spencer argues Jesus deliberately exploits how the Chronicles narrative complicates simplistic assumptions about religious leadership. In 2 Chronicles 28, priests and Levites appear among the victims of divine judgment due to participation in Ahaz's apostasy, while Israelite leaders and common people respond with appropriate compassion.[36] The parable mirrors this reversal: religious professionals fail covenant obligations while the despised outsider fulfills them.

Both narratives function as exposition of Leviticus 19:17-18, which commands: "You shall not hate your kinsfolk in your heart. Reprove your neighbor, but incur no guilt because of them. You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against any of your people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself."[37] The Levitical context proves crucial—the command follows instruction about reasoning with offenders rather than seeking vengeance. Both Oded's call for mercy and Jesus' parable address how covenant people should treat those who have harmed them, requiring love that transcends desire for retaliation.

Why the Priest and Levite Failed

Debunking the Purity Theory

Popular interpretation claims the priest and Levite avoided the victim due to corpse contamination concerns. Jewish purity laws prohibited priestly contact with dead bodies except for immediate family members (Leviticus 21:1-4).[38] This explanation portrays their failure as tragic conflict between competing obligations—ritual purity versus human compassion—rather than simple moral failure.

The theory faces decisive objections. First, both religious figures were traveling "down" from Jerusalem, meaning they had completed temple duties rather than approaching them.[39] They were not protecting ritual status for upcoming service but returning home to Jericho's priestly settlement. Any contamination incurred would not interfere with priestly functions. This directional detail intensifies rather than mitigates their failure to act.

Second, the victim was explicitly "half-dead," not actually dead. Determining his status would require close examination—precisely what the Levite appears to have done by coming to the place and looking. If doubt remained about whether he was alive or dead, purity law demanded investigation rather than assuming death and avoiding contact.[40]

Third, and most decisively, the principle of saving life (pikuach nefesh) took precedence over nearly all other commandments in Jewish legal tradition. Even Sabbath regulations could be violated to preserve life.[41] If the priest and Levite genuinely believed the man might survive with assistance, purity concerns provided no legitimate excuse for inaction. The Mishnah makes explicit: "Whenever there is doubt whether life is in danger, this overrides the Sabbath."[42]

The purity explanation functions as apologetics, softening the parable's sharp critique of institutional religion. Luke shows no interest in presenting the priest and Levite as trapped between competing obligations. The narrative structure emphasizes they "saw" and "passed by"—active choices to avoid involvement rather than tragic necessity forced by ritual requirements.[43]

What Luke Actually Critiques: Institutional Failure

The parable targets institutional religion divorced from covenant obligations. Luke consistently portrays religious professionals as opponents rather than allies of Jesus' mission. Priests and scribes seek to destroy Jesus after he cleanses the temple (19:47). They question his authority and plot his arrest (20:1-2, 19). They hand him over to Pilate demanding crucifixion (23:1-5, 13-25).[44] The Good Samaritan parable fits this broader pattern: religious establishment fails to embody divine mercy it claims to represent.

The specific failures involve emotional intelligence deficits. Spencer's analysis reveals how Luke contrasts emotionally regulated positive characters with emotionally dysregulated opponents.[45] Throughout the Gospel, Jesus and his followers demonstrate appropriate emotional responses—compassion for suffering, joy at restoration, righteous anger at injustice. Opponents exhibit inappropriate emotional responses—rage at healing on Sabbath (6:11), indignation at tax collector's salvation (19:7), mockery at the cross (23:35-37).

The priest and Levite demonstrate emotional disconnection rather than emotional excess. They see human suffering and feel nothing compelling them to act. This emotional void marks them as spiritually bankrupt despite ritual correctness. The text suggests institutional religion can produce professional religionists who perform ceremonies competently while lacking visceral response to human need that characterizes authentic covenant faith.[46]

The critique extends beyond individual failure to systemic problems. Religious professionals become invested in maintaining institutional structures that provide their livelihood, making them unreliable guides to divine will when institutional interests conflict with covenant obligations.[47]

Lawyer's Trap: Rhetorical Strategy

Question Reversal: From Identification to Action

Jesus concludes with question forcing the lawyer to draw his own conclusion: "Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of the robbers?" (10:36).[48] The question reverses the lawyer's original inquiry, accomplishing multiple rhetorical objectives.

First, it eliminates the lawyer's attempt to establish boundaries limiting moral obligation. The lawyer asked "Who is my neighbor?"—seeking to identify legitimate recipients of love. Jesus asks "Who proved to be neighbor?"—shifting focus from identifying deserving recipients to embodying neighborly action. No predetermined categories determine who deserves love. Neighborliness emerges through action rather than predetermined relationship.[49]

Second, the reversal shifts responsibility from identifying deserving recipients to embodying compassionate response. The original question assumed fixed categories—some people are neighbors deserving love, others are not. The revised question makes neighborliness dynamic, emerging through mercy extended regardless of recipient's identity or worthiness.[50]

Third, Jesus' reformulation exposes the lawyer's self-justifying motive. The question "Who is my neighbor?" seeks minimum requirements—how little love can I extend while still fulfilling covenant obligations? The question "Who proved to be neighbor?" demands maximum response—what does authentic love require regardless of convenience or social acceptability?[51]

Fourth, the reversal forces the lawyer (and Luke's readers) into uncomfortable identification. The original question allowed audience to imagine themselves as potential benefactors deciding who merits their compassion. The parable's structure positions audience with the victim—stripped, beaten, vulnerable, dependent on mercy from unexpected source. This shift proves more disturbing than comfortable charity narrative suggests.[52]

Unable to Say "Samaritan"

The lawyer's response reveals the trap's effectiveness: "The one who showed mercy" (10:37).[53] He cannot bring himself to say "the Samaritan." The ethnic designation sticks in his throat, forcing circumlocution that acknowledges the Samaritan's moral superiority while avoiding explicit naming. This linguistic evasion exposes the depth of ethnic prejudice the parable confronts.

Luke's narrative technique proves devastating. The lawyer came seeking to "justify himself" through careful boundary-drawing that would limit moral obligation (10:29). Jesus traps him into acknowledging that authentic covenant faithfulness transcends boundaries the lawyer wanted to maintain.[54]

The lawyer's inability to say "Samaritan" functions as public confession of prejudice. He must choose between maintaining ethnic hostility and acknowledging moral truth the parable demonstrates. His circumlocution represents compromise—conceding the Samaritan's exemplary behavior while refusing full recognition that would require rethinking fundamental assumptions about religious and ethnic identity.[55]

"Go and Do Likewise": But Do What Exactly?

Jesus concludes: "Go and do likewise" (10:37). The command appears straightforward—imitate the Samaritan's compassionate action. But what exactly does "likewise" mean? Does Jesus command humanitarian assistance to anyone in need? Does he call for crossing ethnic and religious boundaries in showing mercy? Does he challenge institutional religion's failure? Does he advocate undermining social hierarchies by elevating despised outsiders as moral exemplars?[56]

The ambiguity proves productive rather than problematic. Different audiences hearing or reading the parable would apply "go and do likewise" according to their situations and challenges. First-century Jewish audiences might hear call to reconsider Samaritan exclusion from covenant community. Gentile audiences might hear challenge to ethnic privilege and social hierarchies. Contemporary readers might hear indictment of boundary-maintenance that excludes refugees, immigrants, or other despised populations.[57]

Alternative interpretations of how to understand this command—particularly Robert Funk's provocative victim-centered reading and Cliff Barbarick's synthetic development of Funk's approach—receive full treatment below in the section "Competing Interpretations: Metaphor vs. Example."

Ecclesiological Dimensions: Who Belongs to Israel?

Samaritans as Part of Biblical Israel

Brown and Yamazaki-Ransom's comprehensive analysis challenges traditional interpretation treating Samaritans as complete foreigners in Jesus' teaching. Their survey of every Samaritan reference in Luke-Acts reveals consistent pattern: Luke presents Samaritans as part of Israel's restoration rather than gentile inclusion.[58]

The evidence proves compelling. When Luke's narrative moves beyond Jerusalem in Acts, the pattern is "Judea and Samaria" (Acts 1:8), then beyond to gentile mission. Philip's Samaritan mission (Acts 8) happens without controversy about incorporating non-Israelites into the church—a stark contrast to the Jerusalem council's heated debate over gentile conversion (Acts 15).[59] The Samaritans are not counted among "the gentiles" but represent stage in Israel's reunification preceding gentile inclusion.

Luke 17:11-19 reinforces this reading. Ten lepers receive healing, but only one returns to thank Jesus—a Samaritan. Jesus asks "Were not ten made clean? But the other nine, where are they?" (17:17), emphasizing the irony that the Samaritan demonstrates proper Israelite response while the presumably Jewish lepers fail gratitude obligations.[60] The narrative does not present the Samaritan as foreigner breaking through to faith but as member of biblical Israel exhibiting authentic worship despite exclusion from Jerusalem temple.

Acts 9:31 provides perhaps the clearest evidence: "Meanwhile the church throughout Judea, Galilee, and Samaria had peace and was built up" (emphasis added). Luke lists Samaria alongside other regions of Israel rather than categorizing Samaritan believers separately. The summary statement indicates completed Israel restoration before gentile mission intensifies.[61]

Restoration Theology Framework

This reading places the Good Samaritan within Luke's broader restoration theology. Jesus as Davidic Messiah reunifies divided Israel before extending salvation to gentiles. The ancient split between northern and southern kingdoms persisted through centuries as Jewish-Samaritan division. Jesus' ministry addresses this fracture through inclusion of Samaritans not as exotic outsiders but as lost siblings returning to covenant family.[62]

The worship dispute between Jerusalem and Mount Gerizim represented fundamental obstacle to reunification. Jesus addresses this by functioning as alternative temple. The Samaritan leper in Luke 17 does not need Jerusalem temple because Jesus provides direct access to divine presence and restoration. This theological move allows Samaritan inclusion without requiring acceptance of Jerusalem temple's exclusive claims.[63]

The Good Samaritan parable participates in this restoration project. By presenting Samaritan as exemplary Torah observer who fulfills Leviticus 19:18 while religious professionals fail, Jesus challenges narrow definitions of Israel that exclude Samaritans from covenant membership based on worship location.[64] The primary issue is not universal humanitarian ethics but proper understanding of covenant boundaries and authentic Israelite identity.

This interpretation does not eliminate the parable's challenging call to cross-boundary mercy. Rather, it situates that call within specific first-century debate about Israel's identity and membership. The parable addresses who belongs to God's covenant people and what authentic covenant faithfulness looks like—questions with ongoing relevance as religious communities continue defining boundaries and evaluating authenticity.[65]

Reinterpreting Leviticus 19:18

From this perspective, Jesus does not universalize Leviticus 19:18's "love your neighbor as yourself" to encompass all humanity. Rather, he demonstrates how Samaritans—as members of biblical Israel—fall within the commandment's scope despite Jewish attempts at exclusion.[66] The revolutionary move is not extending love to all humans regardless of covenant status but challenging definitions of covenant membership that exclude based on worship location or interpretations of ethnic purity.

The lawyer's question "Who is my neighbor?" assumes certain people fall outside neighbor category and therefore outside love obligation. Jesus does not answer "everyone is your neighbor" but rather demonstrates through narrative that the Samaritan whom you exclude from covenant community proves more faithful to covenant obligations than those you consider true Israelites.[67] The challenge strikes at definitions of authentic covenant membership rather than establishing universal ethical obligation transcending covenant categories.

This reading honors the text's Jewish covenantal context while challenging exclusivist interpretations. It avoids supersessionist readings that disconnect the parable from Israel's story, transforming it into generic humanitarian parable divorced from salvation history. Simultaneously, it challenges ethnocentric interpretations that maintain rigid boundaries excluding Samaritans or other disputed groups from full covenant participation.[68]

Competing Interpretations: Metaphor vs. Example

Robert Funk's Provocative Reading

Robert Funk, founder of the Jesus Seminar, offered interpretation fundamentally challenging traditional understanding of the Good Samaritan as "example story." Funk argued the parable functions as metaphor rather than moral example, inviting hearers to identify with the victim rather than the Samaritan.[69]

According to Funk, the crucial question for Jewish hearers was not "How can I be like the Good Samaritan?" but rather "Who among you will permit himself to be served by a Samaritan?" This reframing reveals the parable's radical challenge to ethnic and religious pride. Funk noted: "The Jew who was excessively proud of his blood line and a chauvinist about his tradition would not permit a Samaritan to touch him, much less minister to him."[70]

Funk's interpretation emphasizes that in Jesus' conception of the Kingdom, mercy always comes as surprise, often from unexpected and unwelcome sources. The parable's shock value lies not in calling to humanitarian service but in devastating critique of religious and ethnic superiority. The victim's permission to be served by the Samaritan is inability to resist—only those stripped of all pretense and pride can receive mercy from supposed enemies.[71]

This reading transforms the parable's theological significance. Rather than teaching ethical behavior, the parable reveals the Kingdom's radical inclusivity and surprising sources of divine mercy. As Funk observed: "All who are truly victims, truly disinherited, have no choice but to give themselves up to mercy."[72]

Barbarick's Contextual Development: Love from Below

Cliff Barbarick's 2019 analysis offers synthetic resolution to the apparent conflict between Funk's victim-centered reading and Luke's editorial framework. Rather than choosing between removing the parable from its context or abandoning the victim-identification perspective, Barbarick demonstrates how both can cohere when properly understood. His key insight centers on recognizing that Jesus does more than challenge the lawyer's definition of "neighbor"—he fundamentally redefines what it means to love.[73]

When the lawyer asks, "Who is my neighbor?" following his correct citation of the love command, he reveals his assumed definition of love as "offering benefactions from a position of relative power." As Barbarick explains, the lawyer operates from a framework where "he has; others need. To which of these others should he offer aid?" Jesus' parable dismantles this assumption not by tweaking the definition of neighbor but by overturning the lawyer's entire conception of love itself.[74]

By forcing the lawyer to identify with the victim and recognize the Samaritan as neighbor, Jesus reframes love as "relating to the other from a humble posture of vulnerable need" rather than patronistic charity.[75] The lawyer must acknowledge that loving his neighbor means adopting a position of weakness and openness to receive mercy even from his enemy. Barbarick argues this reading explains why Jesus asks, "Which one was neighbor to the victim?" rather than "Which one treated the victim as neighbor?"—the former question requires adopting the victim's vulnerable perspective.[76]

This interpretation resolves the crux that has troubled scholars: how can "go and do likewise" (10:37) cohere with victim-identification? Barbarick demonstrates that the imperative need not demand shifting identification to the Samaritan if properly understood within his framework of "love from below." The lawyer can imitate the Samaritan's compassionate action, but only if he does so "while firmly anchored in the humble posture of the wounded man."[77]

The critical distinction lies in recognizing that love grounded in awareness of one's own need differs fundamentally from paternalistic benefaction. Barbarick illustrates this through Luke 7:36-50, where the "sinful woman" models love emerging from recognized vulnerability. Her extravagant hospitality toward Jesus flows from deep awareness of her humble position—she offers "love from below" rather than love from power. Jesus presents her as exemplary precisely because her acts of compassion avoid paternalism through being rooted in experienced need.[78]

The lawyer's challenge, therefore, is not simply to help others but to maintain the victim's perspective of vulnerable openness even when in position to offer aid. As Barbarick puts it: the lawyer "needed to experience the ministrations of the Good Samaritan and then go and act likewise."[79] Love defined this way integrates both receiving mercy from unexpected sources and extending mercy from a posture that remembers one's own need.

Connecting the Luke 10 Trilogy

Barbarick's analysis reveals how the Good Samaritan parable connects with both the preceding mission of the seventy (10:1-20) and the following story of Martha and Mary (10:38-42) to create unified theological statement about neighbor-love. This trilogy structure, largely unnoticed by other interpreters, demonstrates Luke's deliberate literary strategy.[80]

When Jesus sends out the seventy, he carefully prescribes their posture: "Carry no purse, no bag, no sandals" (10:4). They must minister from vulnerable dependence, relying on others' hospitality while proclaiming the kingdom and healing the sick. Jesus creates conditions where "their need for the other precedes and grounds their ministry to the other." The seventy proleptically embody the definition of neighbor-love that the parable will illustrate—service emerging from recognized need rather than condescending power.[81]

The Martha and Mary episode continues this theme. Jesus commends Mary, who sits at his feet recognizing her need to listen and learn, while gently correcting Martha, whose service becomes anxious distraction. Barbarick observes that Luke values hospitality highly, yet "in this episode, Jesus reminds Martha that acts of service, if they are going to fulfill the command to love God and neighbor, cannot be unmoored from a posture of vulnerable openness."[82] Mary chooses the better part by maintaining awareness of her need—the same posture the parable demands.

Read together, these three episodes present consistent vision: authentic love operates from below, grounded in recognized vulnerability, whether receiving mercy from enemies, ministering without resources, or sitting humbly at the teacher's feet.

Integration with Luke's Great Reversal Theme

Barbarick's reading connects powerfully with Luke's pervasive "great reversal" motif. Throughout the Gospel, Luke announces salvation involving dramatic status reversals—the lowly exalted, the powerful dethroned (1:51-53). But this raises crucial question: can the great reversal be good news for the wealthy and powerful, or only for the oppressed?[83]

Barbarick argues that Jesus' challenge to the lawyer demonstrates how the reversal offers salvation to those with power and privilege. They suffer from "spiritual dropsy"—clinging to possessions, status, and self-sufficiency that ultimately harm them. Like the man with physical dropsy who needs healing through releasing accumulated fluid, the powerful need healing through releasing their grip on power.[84]

The rich ruler (18:18-27) and Zacchaeus (19:1-10) illustrate this dynamic. The ruler cannot release his wealth and misses salvation. Zacchaeus, aware of his need due to social shame despite his wealth, welcomes Jesus gladly and empties himself of possessions—and receives the pronouncement "Today salvation has come to this house" (19:9).[85]

The Good Samaritan parable fits this pattern precisely. Jesus answers the lawyer's question "How can I inherit eternal life?" by challenging him to release his position of superiority and identify with one who receives mercy from an enemy. The great reversal becomes good news for the powerful when they recognize their own need, release their grip, and risk vulnerability. As Barbarick concludes: "Do this, and he will live."[86]

Traditional Example Story Approach

Most scholarly interpretation maintains traditional example-story reading despite Funk's provocative challenge. The narrative's straightforward structure, lack of obvious allegorical elements, and Jesus' explicit command "go and do likewise" support exemplary interpretation.[87]

This reading emphasizes the parable's practical ethical instruction. Neighbor-love means concrete action crossing social boundaries to address human need. The Samaritan models proper covenant response: seeing suffering, feeling compassion, taking costly action to ensure victim's recovery. The priest and Levite demonstrate failed covenant response: seeing need yet choosing convenient avoidance over difficult mercy.[88]

The example-story approach resonates with Luke's broader ethical emphasis. Throughout his Gospel, Luke presents Jesus teaching practical righteousness addressing real social problems—economic justice, hospitality to outcasts, appropriate use of wealth, mercy toward enemies.[89] The Good Samaritan fits this pattern by providing concrete behavioral model rather than abstract theological principle.

Holding Both Readings in Tension

The interpretive tension between metaphorical disruption and exemplary instruction need not demand exclusive choice. The parable can function on multiple levels simultaneously. As example story, it instructs hearers to cross boundaries showing mercy to anyone in need. As metaphorical challenge, it confronts religious pride preventing reception of grace from unexpected sources.[90]

Different contexts and audiences might emphasize different dimensions. Communities comfortable with their religious status and suspicious of outsiders need the victim-centered reading challenging assumptions about the sources of divine mercy. Communities already marginalized and seeking resources for resistance need the Samaritan-centered reading validating their moral agency despite society's contempt.[91]

Luke's editorial framing does not eliminate the parable's metaphorical power even while directing it toward ethical application. The shock of making a Samaritan the hero continues disrupting comfortable assumptions regardless of whether hearers primarily identify with Samaritan or victim. The parable's enduring power lies precisely in its capacity to function simultaneously as moral instruction and theological provocation.[92]

Contemporary Implications Without Clichés

Who Are Today's Samaritans?

The parable's contemporary application requires identifying not generic "outcasts" but specific enemies—people religious communities consider theologically contaminated, morally compromised, politically dangerous. Samaritans were not simply poor or marginalized but active threats to Jewish religious identity, competitors claiming authentic tradition while rejecting Jerusalem's authority.[93]

Contemporary Samaritans might be religious groups considered heretical by orthodox communities, political movements viewed as existential threats to cherished values, ethnic populations blamed for social problems, or ideological opponents dismissed as morally corrupt. The parable challenges comfortable charity toward the safely marginalized, demanding recognition that those considered enemies might prove more faithful to covenant obligations than religious insiders.[94]

The question becomes personal and uncomfortable: Which groups do I consider so theologically wrong, morally corrupt, or politically dangerous that I would refuse their help even in desperate need? Whose touch would I find contaminating? Whose mercy would I reject as compromising my identity? These questions expose the religious and ethnic pride the parable originally confronted.[95]

Institutional Religion's Ongoing Failure

The priest and Levite represent institutional religion divorced from covenant obligations—religious professionals performing ceremonies competently while lacking visceral response to human suffering. Contemporary parallels appear in churches that maintain doctrinal purity while ignoring poverty, preserve institutional stability while avoiding costly mercy, perfect worship techniques while failing practical neighbor-love.[96]

The critique extends beyond individual hypocrisy to systemic problems. Religious institutions facing financial pressure, political opposition, or cultural marginalization develop institutional interests conflicting with prophetic obligations. Leaders invested in maintaining structures that provide livelihood become unreliable guides to divine will when institutional interests conflict with costly mercy.[97]

Luke's pattern of emotionally dysregulated religious opponents provides diagnostic tool. When religious communities respond to human suffering with indignation rather than compassion, when they prioritize boundary maintenance over mercy, when they defend institutional interests over prophetic obligations, they replicate the priest and Levite's failure regardless of doctrinal correctness or ritual precision.[98]

Uncomfortable Question Reversed

Funk's victim-centered reading poses particularly challenging contemporary question: Who will I permit to help me? The parable forces recognition that salvation often comes through channels we find offensive. The stripping, beating, and abandonment that create the victim's vulnerability parallel the stripping of pretense, pride, and self-sufficiency that enables receiving grace from unexpected sources.[99]

Amy-Jill Levine's interpretation emphasizes this dimension: "Those who want to kill you may be the only ones who will save you."[100] The parable suggests that genuine transformation requires acknowledging dependence on enemies, receiving mercy from those we despise, learning from those we consider theologically wrong. This proves more difficult than offering help to the safely marginalized.

Contemporary application requires honest assessment: Are there groups whose wisdom I refuse to hear, whose mercy I would reject, whose help I consider contaminating? Can I receive correction from political opponents, learn from theological competitors, accept assistance from those whose values I oppose? The parable suggests that maintaining defensive boundaries preventing such reception indicates the pride and self-sufficiency that block divine mercy.[101]

Beyond Universal Love Platitudes

The parable does not teach abstract humanitarian sentiment but concrete, costly, boundary-crossing action. The Samaritan's response required significant resources—wine and oil for treatment, transportation on his own animal, two denarii payment (approximately two days' wages), open-ended commitment to cover additional expenses.[102] This moves beyond feeling compassion or even providing token assistance toward comprehensive engagement ensuring victim's full recovery.

The specificity matters. Neighbor-love means not universal good intentions but particular actions addressing real needs at real cost. The Samaritan did not simply feel bad for the victim or pray for his recovery or donate to general charity. He provided direct, expensive, ongoing assistance to specific person despite ethnic hostility and without expectation of repayment or recognition.[103]

Contemporary application requires similar specificity. Who are the particular people—immigrants, refugees, addicts, mentally ill, formerly incarcerated—whose suffering requires my costly response? What boundary-crossing action does authentic neighbor-love require in my context? What resources must I spend, what risks must I take, what ongoing commitments must I maintain to ensure their restoration?[104]

The parable challenges both individualistic charity that ignores systemic injustice and structural reform that evades personal responsibility. The Samaritan's response addressed immediate individual need through personal action while the broader narrative critique challenges systems producing victims. Authentic neighbor-love requires both personal compassion and structural change—individual transformation and institutional reform operating as complementary rather than competing dynamics.[105]

Conclusion: Convergence of Literary Artistry and Social Challenge

The Good Samaritan episode emerges from this analysis as sophisticated literature serving multiple functions simultaneously. Its seven-part chiastic structure demonstrates literary artistry rivaling anything in ancient Mediterranean literature. Its intertextual connections to 2 Chronicles 28 and Leviticus 19 reveal hermeneutical sophistication using Scripture to interpret Scripture. Its character development and rhetorical strategy create participatory engagement requiring active reader response rather than passive reception.[106]

The sociological dimensions prove equally complex. The parable addresses first-century Jewish-Samaritan conflict through restoration theology challenging narrow definitions of covenant membership. It critiques institutional religion divorced from covenant obligations through devastating portrayal of emotionally disconnected religious professionals. It employs legal rhetoric positioning readers as jury members evaluating competing claims about authentic covenant faithfulness.[107]

Most significantly, narrative and sociological analyses converge to demonstrate how the parable functions through participatory deconstruction. Readers must actively interpret metaphorical meaning, evaluate social arrangements against prophetic standards, and position themselves within the narrative world. This participatory structure means engaging with the parable necessarily involves dismantling comfortable assumptions about legitimate authority, proper boundaries, and the sources of divine mercy.[108]

The enduring power lies not in providing easy answers but in training communities to ask better questions about power, prejudice, and mercy. Who truly embodies covenant faithfulness? What boundaries must be crossed to show authentic neighbor-love? Where does divine mercy originate? Can I receive grace from those I consider enemies? These questions remain as challenging today as in first-century Palestine.[109]

For communities committed to social justice, the Good Samaritan provides what might be called prophetic realism: unflinching critique of institutional failure combined with stubborn insistence that boundary-crossing mercy remains possible. This realism acknowledges that those benefiting from unjust arrangements will resist change, that transformation requires sustained effort across generations, and that communities seeking justice must maintain alternative practices even under hostile conditions.[110]

The parable continues challenging readers to examine how their social arrangements measure against prophetic standards while providing frameworks for imagining and implementing alternative community structures. Its literary sophistication and sociological depth ensure that each generation must wrestle anew with questions about neighbor-love, covenant faithfulness, and the surprising sources of divine mercy. The domestication of the parable into comfortable charity tale represents failure of nerve—refusing to allow the text its full disruptive power in service of maintaining convenient boundaries the narrative systematically dismantles.[111]

Endnotes

[1] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," Westminster Theological Journal 46 (1984): 320.

[2] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" Journal of Theological Interpretation 15, no. 1 (2021): 78.

[3] Jeremy D. Otten, "The Bad Samaritans: The Elijah Motif in Luke 9.51-56," Journal for the Study of the New Testament 42, no. 4 (2020): 465.

[4] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 76.

[5] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 318.

[6] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 332.

[7] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 79.

[8] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 80.

[9] Jeremy D. Otten, "The Bad Samaritans: The Elijah Motif in Luke 9.51-56," 467.

[10] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 81.

[11] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 79.

[12] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 82-83.

[13] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 77.

[14] Jeremy D. Otten, "The Bad Samaritans: The Elijah Motif in Luke 9.51-56," 462-463.

[15] Jeremy D. Otten, "The Bad Samaritans: The Elijah Motif in Luke 9.51-56," 468-470.

[16] Jeremy D. Otten, "The Bad Samaritans: The Elijah Motif in Luke 9.51-56," 476-478.

[17] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 321-322.

[18] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 322-323.

[19] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 319.

[20] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 320.

[21] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 320.

[22] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 320.

[23] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 319.

[24] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 76.

[25] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 156.

[26] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 162-165.

[27] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 145-148.

[28] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 148-152.

[29] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 156.

[30] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 156.

[31] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 156-157.

[32] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 317-335.

[33] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 323.

[34] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 332-333.

[35] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 325-326.

[36] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 327-328.

[37] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 331-332.

[38] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 320.

[39] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 320.

[40] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 320-321.

[41] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 321.

[42] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 321.

[43] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 320.

[44] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 77.

[45] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 158-160.

[46] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 159.

[47] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 160.

[48] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 334.

[49] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 334.

[50] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 335.

[51] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 334.

[52] Robert W. Funk, "The Good Samaritan as Metaphor," as cited in Cliff A. Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context: Retrieving and Developing Robert Funk's Provocative Reading," in Ethics in Context: Essays in Honor of Wendell Lee Willis (2019).

[53] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 334.

[54] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 334-335.

[55] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 91.

[56] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 335.

[57] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 92.

[58] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 75-93.

[59] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 86-88.

[60] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 85.

[61] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 89.

[62] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 90-91.

[63] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 85.

[64] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 91-92.

[65] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 92.

[66] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 332.

[67] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 334.

[68] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 92-93.

[69] Robert W. Funk, "The Good Samaritan as Metaphor."

[70] Robert W. Funk, "The Good Samaritan as Metaphor."

[71] Robert W. Funk, "The Good Samaritan as Metaphor."

[72] Robert W. Funk, "The Good Samaritan as Metaphor."

[73] Clifford A. Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context: Retrieving and Developing Robert Funk's Provocative Reading," in Ethics in Context: Essays in Honor of Wendell Lee Willis (2019), 2, 12.

[74] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 12.

[75] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 2.

[76] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 12.

[77] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 14.

[78] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 14.

[79] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 14.

[80] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 15-17.

[81] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 17.

[82] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 16.

[83] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 17-18.

[84] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 18.

[85] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 18-19.

[86] Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context," 19.

[87] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 318.

[88] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 335.

[89] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 77.

[90] Cliff A. Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context."

[91] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 92.

[92] Cliff A. Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context."

[93] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 79-81.

[94] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 92.

[95] Robert W. Funk, "The Good Samaritan as Metaphor."

[96] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 160.

[97] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 160.

[98] Patrick E. Spencer, "Emotional Characterization in Luke-Acts as an Archetype for Emotional Intelligence," 158-160.

[99] Robert W. Funk, "The Good Samaritan as Metaphor."

[100] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 92.

[101] Robert W. Funk, "The Good Samaritan as Metaphor."

[102] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 322-323.

[103] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 323.

[104] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 92.

[105] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 335.

[106] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 321-322.

[107] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 75-93.

[108] Cliff A. Barbarick, "The Parable of the Good Samaritan in Context."

[109] F. Scott Spencer, "2 Chronicles 28:5-15 and the Parable of the Good Samaritan," 335.

[110] Jeannine K. Brown and Kazuhiko Yamazaki-Ransom, "Are the Samaritans 'the Gentiles' in the Lukan Narrative?" 92-93.

[111] Robert W. Funk, "The Good Samaritan as Metaphor."

When Your Enemy Saves Your Life | The Good Samaritan Reversal | Dr. Cliff Barbarick